Professor Birnbaum was a gem of a colleague. He always had time to talk and always said something worth listening to and remembering. He did much to make Georgetown the outstanding university it became. Coming to know him and share thoughts with him was a significant part of the outstanding life at the University. He will be surely missed by all who had the pleasure and honor of knowing him.

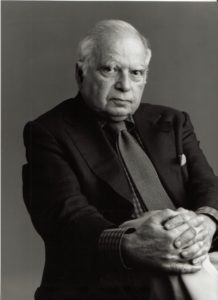

In Memoriam: Professor Norman Birnbaum

January 11, 2019

Norman Birnbaum, a leading intellectual of the 20th Century left who taught at Georgetown Law for 22 years and remained actively involved with the Law Center in retirement, passed away on Jan. 4. He was 92.

“A true renaissance man, Norman was a sociologist, journalist, teacher, scholar and author, and we were fortunate to have him as a member of our community for almost 40 years,” said Georgetown Law Dean William M. Treanor. “I will miss him greatly. His sparkle, erudition, love of debate and passion for justice were a treasure, and it was a joy to know him.”

“A true renaissance man, Norman was a sociologist, journalist, teacher, scholar and author, and we were fortunate to have him as a member of our community for almost 40 years,” said Georgetown Law Dean William M. Treanor. “I will miss him greatly. His sparkle, erudition, love of debate and passion for justice were a treasure, and it was a joy to know him.”

Born in Harlem in 1926, Birnbaum was raised in the Bronx by an intellectually restless schoolteacher father and a homemaker mother, who, he later wrote, “didn’t know what to do with me” as Birnbaum discovered his own passion for reading about far-flung places and ideas. His mainly secular upbringing was most Jewish in its emphasis on learning, he wrote in his 2018 memoir.

He was 12 when he felt the formation of his social consciousness in the “terrible year” of 1938, which marked Kristallnacht in Nazi Germany, his own brush with gleeful anti-Semitism from taunting boys on the streets of New York, and an awakening to American injustices through the works of John Dos Passos, Sinclair Lewis and Upton Sinclair.

Birnbaum attended Williams College and then got his doctorate in sociology at Harvard University. Before Georgetown, Birnbaum was on the faculty at Amherst College and taught at a half dozen world-famous European universities, including Oxford University (where he introduced sociology to the undergraduate curricula) and the London School of Economics.

Along his intellectual journey, he embraced socialism, rejected communism and admired the idealism of the student demonstrations in 1968, offering theoretical underpinnings for the progressive movement youth leaders sought to build. He became an active member of the “New Left,” identifying with and befriending many of the leading figures of Europe’s social democratic movement, including Germany’s Willy Brandt and France’s Francois Mitterand.

He served as an advisor to his friend Edward Kennedy’s presidential campaign, a consultant to the National Security Council, an advisor to the United Automobile Workers, the chair of the Policy Advisory Council of the New Democratic Coalition, a member of the editorial board of Partisan Review and, later, The Nation, one of his father’s favorite publications. He also was on the founding editorial board of New Left Review.

Coming to Georgetown Law in 1979, Birnbaum at last found “a welcoming academic home,” writing in his memoir that students were cared for, staff were appreciated, and Deans actually listened to their colleagues. “The faculty experienced a sense of triumph as it realized that it was mastering a difficult task, transforming a somewhat local and culturally specific institution into a multi-faceted national one. Georgetown kept its Jesuit identity as best it could… and certainly retained its connections to Congress and government,” he wrote.

He was a great admirer of Catholic social gospel as well as Georgetown’s embrace of religious and social diversity. He wrote of his friendship with Georgetown President Timothy Healy, S.J., who first brought him to the university, and his appreciation for successors, including current University President John DeGioia, who took a seminar with Birnbaum while studying for his doctorate in philosophy.

Birnbaum joyfully taught a class with another Jewish New Yorker of his generation, but from the other side of the political spectrum, Professor Warren Schwartz, a founder of the conservative law and economics movement. He credited his “most rewarding pedagogical experience” to his friend and colleague Professor Louis Michael Seidman, who had helped create what is now called Georgetown’s “Curriculum B” option for 1Ls. Birnbaum took responsibility for the course on justice in the alternative first-year curriculum that blends an introduction to legal theory with philosophical and social analysis.

“A constant font of culture and ideas, Norman’s presence always contributed to the intellectual life and vibrancy of Georgetown Law,” said Michael Goldman, the Law Center’s Jewish Chaplain.

Considered the Law Center’s resident “man of letters,” Birnbaum often taught a lecture course on the classics of social thought, from Rousseau to Freud, as well as elective seminars delving into his favored themes of class, social responsibility and the diversity of American religious life. Europe, too, was a recurring focus, from the Holocaust, fascism, Nazism and communism to the postwar welfare states; although, in his memoir, Birnbaum bemoaned the lack of available teaching materials to give the last of those – the focus of much his own work – its just due.

Birnbaum’s books included The Crisis of Industrial Society (1969), The Radical Renewal (1988), Socialism Reconsidered (1996) and After Progress: American Social Reform and European Socialism in the Twentieth Century (2001). After retirement, he worked with the Law Center’s Special Collections Librarian Hannah Miller-Kim on pulling his papers into a 50-box collection for the Briscoe Center on American History at the University of Texas at Austin, before turning to his nearly 700-page memoir, From The Bronx to Oxford and Not Quite Back. “It was truly his magnum opus,” Kim said.

In 2015, Birnbaum stepped in for Georgetown Law Professor Ladislas Orsy, S.J., who broke his leg, to finish teaching his Philosophy of Law course, and just this past September at a faculty workshop presented his paper, “Floating in Historical Space: A Ninety-Two-Year-Old Confronts the Chaos of the Twenty First Century.” Birnbaum was forever shaped by the “hothouse of ideas and argument” of the active New York Jewish left intelligentsia that he joined in the 1930s, said Seidman, who considered his friend a mentor and a role model.

“One thing that is just extraordinary about Norman is that many of his peers, many of the leading figures of that movement became disillusioned and bitter and moved strongly to the right,” Seidman said. “They became neoconservatives. But Norman never moved an inch. He was somebody who to his dying day cared deeply about social justice and spent his entire academic career working for people at the margins of society. He was vibrant, aware, and committed up to his final illness.”

In recent years, Birnbaum was dismayed by ascendant right-wing political movements across Europe, as well as by the current inhabitant of the White House, Seidman said.

“But he was never pessimistic,” he said. “He had a wry sense of humor and took the long view. He thought in the end good sense would prevail and that people would ultimately see what was in their interests. He was an optimist, but certainly a realistic one.”

Birnbaum was previously married twice, to Nina Apel and Edith Kurweil. He is survived by his daughter Antonia Birnbaum, a Paris-based philosopher, a grandson, and his partner Terry Flood. His other daughter, Anna Birnbaum, died in 2011.

The Law Center will hold a memorial on March 1 to honor Birnbaum.

While working the reference desk I often received calls from a very polite, but affable, professor emeritus -- Norman Birnbaum. Often his first question was "how is your German?" and I would reply: "Rudimentary, but I can figure things out." And then he would go on to say "could you kindly find this article" in a myriad of German newspapers.

Even though our chats were brief I always enjoyed hearing from him and the inevitable hunt to find and access whatever he was looking for. I will miss picking up the line and hearing "Hello! This is Professor Birnbaum!"

Norman was a true Uomo Universale and one of the kindest most urbane people I have ever met. His wry wit, humor and impish way, were evident even in chance encounters in the hallway.

Upon any encounter with him one always felt he was personally interested in what you had to say and your life; and he always had an enriching and pithy commentary on the events of the day concerning the broader society. I always came away feeling wiser and in ever closer connection with him. He had this warm manner, almost as though he was sharing an intimate secret with you.

Though very critical of much that was occurring in the country and broader world, there was an optimism there. By connecting world events with his vast sweep of experiences, readings, and travel, over a long period of time, he imparted a sense that “this too will pass” and humanity will be OK.

I took one of Dr. Birnbaum’s courses at night while working in the Office of Counsel to the President at the White House in the final years of the Clinton Administration. I was a bit distracted from law school, but not from him. He was riveting, a holistic mind and character with a remarkable wit. I rarely missed one of his classes despite an otherwise sub-optimal attendance record.

During the Elian Gonzalez affair, and homebound by a snowstorm, he wrote me, off the top of his head – while I was at the White House - about his memory of a Soviet boy who rode his bicycle into a Western part of Berlin. The Eisenhower administration corresponded with General Zhukov about the matter, as I remember his letter, and the boy was sent back to the Soviet Republic shortly thereafter. Professor Birnbaum suggested this might be a precedent for sending the Gonzalez boy back home. On reading his note, I immediately called the librarian at the Eisenhower library. There was definitive, corroborating evidence of Birnbaum’s recollection, which I imagined must have popped into his head as he was stirring a scotch or was waxing poetic about his Red Star dossier or something. In any event, I drafted a memorandum for then-White House Chief of Staff John Podesta, including Birnbaum’s letter and the corroborating evidence as attachments. Weeks later, John thanked me. I thanked the Good Professor. And Elian went home.

I was not and am not a memorable or meaningful intellect as he was, but we connected personally and I so enjoyed his company. We laughed during office hours about “two Jews who walked into a Jesuit University and felt so comfortable and accepted we naturally craved some sort of supplemental disapproval” from the nearest available Jewish mothers. We marveled at the Jesuit passion for education and learning. We loved Georgetown. We corresponded for several years following my graduation, and I saw him once for a coffee in the early 2000s. Then, we fell out of contact. But I have never lost touch with him. And while he may have forgotten me, he has never lost his touch with me. He was a towering intellectual and a person I admired. He instilled in me a hunger to persist in learning, at every turn. And he was just utterly hilarious.

Baruch Dayan HaEmet. Your memory is a blessing. You are with me, and I am with you. You have enriched me forever and you have repaired the world, and you were loved.

In addition to his tenure at GULC, Prof. Birnbaum had a joint appointment in GU's Department of Government for a few years. He was a brilliant, inspiring, hilarious man, and one of the most encouraging professors I've ever encountered. I will always be grateful to him for pivotal advice.

In the fall of 2016, briefly after Donald Trump was elected President of the United States, there was an event at the Law Center to discuss the impact of the elections. Norman Birnbaum was there as well. Several attendees said that they never felt as upset about an election as they did in 2016. Then, toward the end of the event, Norman Birnbaum spoke up and asked people to keep things in perspective. I don't recall his exact words, but he said something along the lines of: "I understand that you are upset, but remember that I have felt this bad my entire life." He got a big laugh and managed to cheer everyone up.

I thought that this story summed up a lot about him -- it was witty, it was perceptive, and it was -- in its own way -- empathetic and encouraging.

I will miss him and his wonderful political columns for the German daily taz very much.

When I returned briefly to Georgetown for my Ph.D.-research funded by DAAD in 1993, I chose voluntarily to take part in Prof. Birnbaum's political/historical lecture on 'Dictatorships during the 20th century'. I also volunteered to write a seminar work based on the the Book by Lifton "The Nazis doctors". The book dealt among others with the unbearable atrocities against mentally sick children and adults, named with the perverted euphemistic phrase of "Euthanasie" (which literally translated means 'Good death').

It also introduced me into the knowledge on how German mental hospitals committed atrocities against middle aged men, who were former soldiers during World War I / The Great War. These disabled men, physically and mentally handicapped men, whose disabilities derived from sacrificing their mental and physical health as mandatorily or voluntarily engaged young men for "Kaiser and Vaterland" stays in my awareness for ever.

Prof. Birnbaum influenced my way of thinking about "patriotism" and the face value of it.