Blacklisting as a Proxy for Foreign Policy: Trump’s Attempt to Designate the Houthis as a Foreign Terrorist Organization

December 2, 2020 by Digital Editor

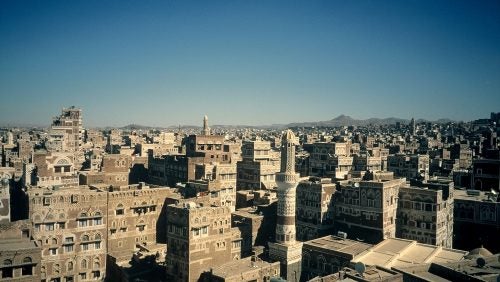

Sana'a, Yemen/Hiro Otake (https://www.flickr.com/photos/49786373@N00/355823025)

By: Emma Oliver

The Trump administration is reportedly taking steps to designate the Houthis, a minority Yemini Shiite rebel group, as a foreign terrorist organization (“FTO”). This new development could jeopardize the ongoing negotiations between Saudi Arabia and the Houthis for a ceasefire and harm those most vulnerable to the violence – civilians.

Originally emerging from Yemen’s northern province, Saada, in the 1980s, the Houthis’ influence in the region has grown tremendously since they took control of Yemen’s former capital, Sanaa, in 2014. Things took a turn for the worse when Saudi Arabia intervened in Yemen’s civil war the next year, prompting ongoing violence between the nation and the Houthis for the past six years. The United States entered the conflict under the Obama administration by providing military support to Saudi Arabia, a move former officials say they regret, but Trump has continued to escalate the U.S.’s role in the war. The U.S. has toyed with idea of designating the Houthis as an FTO before, with Trump sparking rumors of a designation as recently as 2018, but have so far retracted their efforts, largely due to humanitarian concerns.

Designation as a foreign terror organization has serious implications and isn’t always an effective tool in achieving foreign policy objectives. If history is any indication, designation will only serve to strengthen the Houthi’s ties with Iran and exacerbate violence by cutting off negotiations between the combatting groups. Since its original 1997 designation as an FTO by the United States, Lebanon-based Hezbollah has only grown its reach and solidified its ties with Iran. Similarly, Save the Children CEO Janti Soeripto points to the Obama administration’s FTO designation of Al-Shabaab in Somalia as “deter[ring] risk-averse banks from transferring money in the country and slow[ing] the work of relief agencies amid a deadly famine that killed an estimated 250,000 people in 2011.” Even proscription on a less “significant” list like the Treasury Department’s Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons List (SDN) or the State Department’s Terrorist Exclusion List (TEL) can have a chilling effect on peacebuilding and democratic reform. In placing the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) on the TEL list, the US missed an opportunity to “isolate the elements [within the Maoist leadership] that opposed negotiations and nonviolent political contestation.”

Even more, the designation will worsen the crisis in Yemen. Knowingly providing material support or resources to a designated FTO is punishable by up to twenty years in prison under 18 U.S.C. 2339(B), and because of the statute’s extraterritorial jurisdiction provisions, the United States has the power to prosecute any group or individual, domestic or international, that does so. Material support or resources has been broadly defined by the Supreme Court in its landmark decision, Holder v. Humanitarian Law Project, and includes even those resources intended to support an organization’s humanitarian and political activities. For example, a U.S.- affiliated NGO who provides legal expertise to a designated group on appealing to international organizations or on political advocacy training may potentially be prosecuted.

This complication is especially problematic as 80% of the Yemen population needs some form of aid. Just this year, the U.S. Agency for International Development suspended funding to the northern region in response to Houthi’s obstruction of aid, only to appropriate new emergency aid two months later at the urging of the humanitarian community. However, once Trump designates the Houthis as a foreign terrorist organization, humanitarian groups will no longer be able to provide aid to Yemeni civilians without risk of criminal prosecution since coordination with the “de facto” authority is necessary to carry out their programs.

Once the designation is made by an administration, it’s even harder to revoke. If Trump designates the Houthis as an FTO, Biden will have to wait until after Congress confirms his pick for Secretary of State to revoke the designation. With Trump’s refusal to concede and potential for a confirmation fight, it could be well into the new year before a policy reversal. Revocation can also be accomplished through an Act of Congress, but this seems like an even longer shot than an administration change. A designated group also has legal recourse, by requesting judicial review before the D.C. circuit within 30 days of the designation. However, this option is basically a dead end given the reluctance of the court to provide the access to the evidence necessary for groups to challenge their designation.

The Trump administration should follow the advice of seasoned foreign policy and national security experts and refrain from designating the Houthis as an FTO.

Emma Oliver is a 2L at Georgetown University Law Center, where she is a staff editor for the Georgetown Journal of International Law. She graduated from the University of Houston with honors in 2014, with a degree in Political Science and National Security Studies. Prior to law school, she served in the City of Houston’s first Mayor’s Office of Education where she spearheaded initiatives to increase educational and economic opportunities for the city’s youth. She also previously held various roles in education policy in the Texas legislature and as a consultant for UNICEF USA, Harris County Department of Education, and other nonprofit organizations.