Generative AI’s Other Environmental Problem

October 14, 2025 by Liza Williams

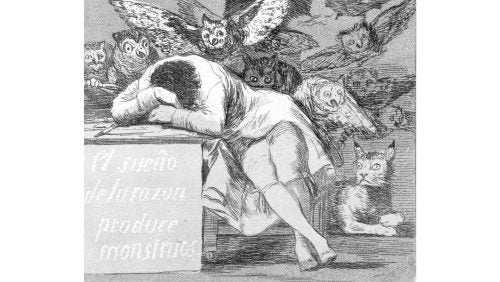

“The sleep of reason produces monsters.” Francisco Goya, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons. A person asleep at a desk with the phrase “el sueño de la razón produce monstruos,” or “the sleep of reason produces monsters” written on the side and monsters in the background.

An overreliance on generative AI may threaten our collective potential to meaningfully address environmental problems by potentially slowing scientific progress and innovation, reducing the efficacy of our collaboration, and weakening support for environmental protection.

Introduction

The widespread adoption of generative AI[1] has drawn attention for its negative environmental impact, including its high demand for energy, water, and Graphics Processing Units (GPUs).[2] Generative AI may, however, have another, less direct environmental effect by limiting our capacity to develop and implement environmental solutions. Although generative AI has some beneficial applications for environmental issues,[3] overreliance on the technology could stymie our ability to meaningfully address environmental challenges, necessitating a more thoughtful approach.

Environmental problems—including climate change, pollution, biodiversity loss, water scarcity, and ocean acidification—present unique challenges. From a legal perspective, the challenge of addressing environmental problems stems from: the uncertainty of a limited understanding of the natural environment; their multiple causes and dynamic effects; the distance between environmental injuries and their cause; and the noneconomic, nonhuman character of ecological injuries.[4] Overcoming these challenges requires a strong understanding of environmental problems, innovation, effective collaboration, institutional reform or restructuring, and compassion. Generative AI poses a threat to each of these capacities, and thus to our potential for cultivating environmental resilience.

Generative AI may slow scientific progress and innovation

As climate change continues to have destabilizing effects, environmental problems will evolve, requiring novel understandings[5] and innovation to facilitate adaptation.[6]

Generative AI, however, may slow scientific progress. Although AI improves individual scientists’ productivity, it reduces the diversity of scientific content.[7] Generative AI may also slow scientific progress by exacerbating the production–progress paradox of science, wherein increases in the number of scientific research papers aggravate the inequality of attention, such that only the most popular papers are read.[8] Scientists are incentivized to limit their research to already-popular topics rather than conduct riskier but potentially ground-breaking research.[9] If generative AI slows scientific progress, our understanding of evolving environmental problems will erode.[10]

The negative cognitive impacts of generative AI may also impede progress in understanding environmental problems. A recent study found that participants experienced “weaker neural connectivity” when they wrote essays using ChatGPT than when they wrote unaided.[11] Weakened neural connectivity may reduce the likelihood that an individual will identify cross-disciplinary connections that could aid understanding of environmental problems or inspire innovation.

Generative AI cannot compensate for its negative cognitive impact because it is not a more promising substitute for humans in addressing environmental problems. Generative AI works within existing frameworks to generate content that mimics the content in its training data.[12] As such, any novelty it produces will be modest, at best. Because innovation is necessary to respond to environmental challenges, generative AI’s limited novelty threatens our ability to develop solutions.

Overreliance on generative AI limits our collective potential

Addressing environmental challenges requires collaboration across disciplines,[13] institutions, and jurisdictions.[14] Because a single person or solution is inadequate to resolve the enormity of environmental problems, our ability to foster environmental resilience turns on our collective potential.

Overreliance on generative AI threatens this collective potential by weakening the efficacy of collaboration. The accuracy of a group’s collective judgment is improved when individuals employ their diverse approaches and correct each other’s errors.[15] Collective judgment suffers, however, when individuals’ approaches converge as a result of relying on a few generative AI tools.[16] Further, although generative AI improves the efficiency of communication between individuals, it does so by superficially resolving discrepancies, when conflict can be essential for creating a high-quality solution.[17] The tendency of generative AI to veil nuance is particularly concerning because reductionism itself poses a threat to solving environmental problems.[18] By potentially reducing the efficacy of our collaboration, generative AI threatens our ability to develop effective environmental solutions.

Further, generative AI has a homogenizing effect even as individuals benefit from its use. A study on the effect of generative AI on creativity found that short stories written with generative AI had less variety as a group than stories written unaided, even as the AI-assisted stories were more creative individually.[19] Thus, generative AI may enhance individual creativity at the expense of collective creativity.[20]

This homogenizing effect is a feature of generative AI’s design. Because generative AI is trained on the internet, its output reflects the perspectives and topics most represented online, those with the highest frequency in the training data.[21] As a result, generative AI has a bias toward English and other “high-resource languages.”[22] Knowledge and perspectives less featured on the internet, like those of Indigenous peoples, are underrepresented or excluded.[23]

As generative AI washes away nuance and different modes of thought, it cements the status quo and limits our capacity to question present assumptions.[24] If meaningfully addressing environmental problems requires something akin to a paradigm shift, our legal system, policies, social values, and business practices would need to rest on a different set of assumptions than those we have today. By limiting our capacity to question these assumptions, generative AI hinders our ability to create the environmental resilience that would require such a reordering.

The use of generative AI may also, by limiting opportunities for connection, weaken collective support for environmental protection. Rather than confiding in, confronting, and collaborating with another person who understands[25] our words through the lens of lived experience, we turn to the chatbot, which is devoid of personal experience. The chatbot allows us a frictionless, sterilized exchange at the expense of a deeper understanding of the real challenges faced by others. As a result, we become less empathetic, less attuned to collective needs, and less inclined to propose and support measures that would protect our environment. Because limited social and political support for environmental protection is already a significant barrier to reform, a further weakening of this support may prohibit us from implementing environmental reform.

Generative AI as a tragedy of the commons and the need for regulation

Generative AI is a kind of tragedy of the commons. Under the theory of the Tragedy of the Commons, individuals are incentivized to maximize their use of common resources because the individual benefit of the use exceeds the individual negative impact of the use, leading to the deterioration of the resource.[26] The common resource at risk with generative AI is our collective capacity—or more specifically, scientific progress, effective collaboration, and empathy. Generative AI boosts individual scientists’ careers but slows scientific progress;[27] it improves individual creativity but homogenizes content. Individuals are incentivized to use generative AI because the individual benefit outweighs their share of the collective harm.

Because “[f]reedom in a commons brings ruin to all,”[28] mitigating the collective harms of generative AI requires regulation. Congress has yet to establish broad regulatory authority over AI,[29] and the limited regulatory progress under Executive Order 13859[30] suggests a need for a more centralized and comprehensive approach.[31]

Drawing inspiration from federal environmental law, future legislation regulating generative AI could vest regulatory authority in a single agency, include a savings clause to prevent preemption of state regulatory efforts, [32]and establish a private cause of action, like a citizen suit provision, authorizing the public to sue for violations.[33]Generative AI legislation could require notice and disclosure of generative AI usage,[34] prohibit high-risk uses,[35] and regulate use of generative AI across the federal government.[36]

Allowing the use of generative AI to continue unchecked is choosing a free-for-all over sustainable growth, convenience over honest communication, productivity over potency, and individual benefit over societal good.[37] These same value choices pose a threat to meaningful environmental reform. Creating and implementing effective and just environmental solutions requires intervening in the unbridled proliferation of generative AI.

[1] Kevin Roose & Casey Newton, Everyone Is Using A.I. for Everything. Is That Bad?, N. Y. Times (June 16, 2025), https://www.nytimes.com/2025/06/16/magazine/using-ai-hard-fork.html; Ian Bogost, College Students Have Already Changed Forever, Atlantic(Aug. 17, 2025), https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2025/08/ai-college-class-of-2026/683901/.

[2] Adam Zewe, Explained: Generative AI’s Environmental Impact, Mass. Inst. Tech. News (Jan. 17, 2025), https://news.mit.edu/2025/explained-generative-ai-environmental-impact-0117. GPUs are processors that manage generative AI workloads, and their production is energy-intensive and requires raw materials mined through often environmentally harmful processes. Id. See also Schumpeter, Generative AI Has a Clean-Energy Problem, Economist (Apr. 11, 2024), https://www.economist.com/business/2024/04/11/generative-ai-has-a-clean-energy-problem; Shaolei Ren & Adam Wierman, The Uneven Distribution of AI’s Environmental Impacts, Harv. Bus. Rev. (July 15, 2024), https://hbr.org/2024/07/the-uneven-distribution-of-ais-environmental-impacts.

[3] See, e.g., Daniel Richards et al., Harnessing Generative Artificial Intelligence to Support Nature-Based Solutions, 6 People and Nature 883, 883–84 (finding that generative AI can facilitate identifying nature-based solutions to environmental problems on a local level); AI Has an Environmental Problem. Here’s What the World Can Do About That, U.N. Env’t Programme (Sep. 21, 2024), https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/ai-has-environmental-problem-heres-what-world-can-do-about (suggesting that AI can help address some aspects of climate change, nature and biodiversity loss, and pollution and waste because it can be a helpful tool for environmental monitoring, helping institutions and individuals make sustainable choices, and improve efficiencies).

[4] Richard J. Lazarus, Restoring What’s Environmental About Environmental Law in the Supreme Court, 47 UCLA L. Rev. 703, 744–48 (2000).

[5] One mechanism of the destabilizing impact of climate change is “climate tipping points,” where warming causes critical thresholds to be crossed, which can “tip a natural system into an entirely different state and lead to potentially irreversible, catastrophic impacts for the planet.” Courtney Lindwall, Climate Tipping Points Are Closer Than Once Thought, Nat. Res. Def. Council (Nov. 15, 2022), https://www.nrdc.org/stories/climate-tipping-points-are-closer-once-thought.

[6] See Juanita Constible, We Can and Must Adapt to Climate Impacts Now, Nat. Res. Def. Council (Feb. 28, 2022), https://www.nrdc.org/bio/juanita-constible/we-can-and-must-adapt-climate-impacts-now (reviewing the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Working Group II report and arguing that action is needed to respond to “unavoidable and compounding climate hazards”).

[7] Qianyue Hao et al., AI Expands Scientists’ Impact but Contracts Science’s Focus, arXiv (2024), 10.48550/arXiv.2412.07727 (empirical study finding that AI-augmented research benefitted individual scientists’ careers but narrowed the topics studied, suggesting that AI may reduce scientific diversity and broad engagement). “On average, the use of AI helps individual scientists publish 67.37% more papers, receive 3.16 times more citations, and become team leaders 4 years earlier.” Id. at 8.

[8] Sayash Kapoor & Arvind Narayanan, Could AI Slow Science?, AI As Normal Technology (July 16, 2025), https://www.normaltech.ai/p/could-ai-slow-science.

[9] Id.

[10] But see, Michael H. Huesemann, Can Pollution Problems Be Effectively Solved by Environmental Science and Technology? An Analysis of Critical Limitations, 37 Ecological Econ. 271, 271 (2001) (“[S]cience and technology have only very limited potential in solving current and future environmental problems. Consequently, it will be necessary to address the root cause of environmental deterioration.”)

[11] Nataliya Kosmyna et al., Your Brain on ChatGPT: Accumulation of Cognitive Debt When Using an AI Assistant for Essay Writing Task, arXiv (2025), https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2506.08872. The study is yet to be peer reviewed. Andrew R. Chow, ChatGPT May be Eroding Critical Thinking Skills, According to a New MIT Study, Time (June 23, 2025), https://time.com/7295195/ai-chatgpt-google-learning-school/. See also Michael Gerlich, AI Tools in Society: Impacts on Cognitive Offloading and the Future of Critical Thinking, 15 Societies 6 (2025), https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15010006 (finding a “significant negative correlation between frequent AI tool usage and critical thinking abilities, mediated by increased cognitive offloading” from surveys and interviews with 666 participants).

[12] Zewe, supra note 2.

[13]Robert Costanza & Sven Erik Jørgensen, Understanding and Solving Environmental Problems in the 21st Century: Toward a new, integrated hard problem science 1 (Robert Costanza & Sven Erik Jørgensen eds., 2002).

[14] See, e.g., Hans-O. Pörtner et al., Summary for Policymakers, Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (“Climate resilient development is facilitated by international cooperation and by governments at all levels working with communities, civil society, educational bodies, scientific and other institutions, media, investors and businesses; and by developing partnerships with traditionally marginalised groups, including women, youth, Indigenous Peoples, local communities and ethnic minorities.”).

[15] Jason W. Burton et al., How Large Language Models Can Reshape Collective Intelligence, 8 Nat. Hum. Behav. 1643, 1649–51 (2024), https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-024-01959-9.

[16] Id.

[17] Id. at 1651 (“What may be perceived as inefficiency or conflict in the moment could instead be necessary to cultivate the transient diversity needed to reach a high-quality solution.”).

[18] Oran R. Young & Olav Schram Stokke, Why Is It Hard to Solve Environmental Problems? The Perils of Institutional Reductionism and Institutional Overload, 20 Int’l Env’t Agreements 5, 8–9 (2020), https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-020-09468-6 (defining reductionism as the oversimplification of a problem).

[19] Anil R. Doshi & Oliver P. Hauser, Generative AI Enhances Individual Creativity But Reduces the Collective Diversity of Novel Content, 10 Sci. Adv. 28 (2024), https://doi/10.1126/sciadv.adn5290.org (The effect was especially pronounced for the less-creative participants); Id. at 7.

[20] Id. See also Kosmyna et al., supra note 11 (finding that essays written with ChatGPT were less diverse as a group than those written without the technology).

[21] Burton et al., supra note 17 at 1656.

[22] Cal. Gov’t Operations Agency, Benefits and Risks of Generative Artificial Intelligence (Nov. 2023).

[23] This is especially concerning because Indigenous communities and non-English-speaking populations are among the communities most vulnerable to the effects of climate change. See Constible, supra note 6. Further, the IPCC found that “[p]rospects for climate resilient development are increased by inclusive processes involving local knowledge and Indigenous Knowledge.” Pörtner et al., supra note 14 at 33.

[24] Automation bias, the seeming phenomena wherein users of generative AI are more likely to favor its output over human-generated content, may serve to further this effect. Irina Carnat, Human, All Too Human: Accounting for Automation Bias in Generative Large Language Models, 14 Int’l Data Priv. L. 299, 299 (2024).

[25] “Large language models like Claude cannot make any connection between the words they produce and the things in the world that those words refer to, for the simple reason that LLMs have no conception of the world.” Adam Becker, The Useful Idiots of AI Doomsaying, Atlantic (Sep. 19, 2025), https://www.theatlantic.com/books/archive/2025/09/what-ais-doomers-and-utopians-have-in-common/684270/.

[26] Garrett Hardin, The Tragedy of the Commons, 162 Science 1243, 1244 (1968). Individual use of a common resource, such as a pasture open to all, has a positive benefit to that individual but a negative impact on the resource. Id. Because, however, the negative impact of the resource is spread across all users, the magnitude of the negative impact is significantly smaller than that of the benefit to the individual user. Id.

[27] Hao et al., supra note 7.

[28] Hardin, supra note 29.

[29] Laurie Harris, Regulating Artificial Intelligence: U.S. and International Approaches and Considerations for Congress, Cong. Res. Serv.(2025), https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R48555 (finding that federal regulatory efforts currently focus more on assessing potential regulatory authority and federal governmental use of generative AI than on regulating private industry).

[30] Exec. Order No. 13,859, 84 Fed. Reg. 3967 (Feb. 11, 2019). But see Disclosure and Transparency of Artificial Intelligence-Generated Content in Political Advertisements, 89 Fed. Reg. 63381 (Aug. 5, 2024).

[31] Alex Engler, The EU and U.S. Diverge on AI Regulation: A Transatlantic Comparison and Steps to Alignment, Brookings (Apr. 25, 2024), https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-eu-and-us-diverge-on-ai-regulation-a-transatlantic-comparison-and-steps-to-alignment/ (highlighting the benefits of the more “more centrally coordinated and comprehensive regulatory coverage” of the EU’s approach to generative AI regulation as compared with the approach in the United States).

[32] See, e.g., 33 U.S.C. § 1251(g).

[33] See, e.g., 42 U.S.C. § 7604.

[34] See, e.g., Engler, supra note 31 (explaining the proposed AI Act in the EU, which requires disclosure of certain AI applications, like chatbots and deepfakes); Office of Sci. & Tech. Pol’y, Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights, White House, https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/ostp/ai-bill-of-rights/ (2022) (calling for notice and explanation of automated systems); Kevin C. Desouza, How Different States are Approaching AI, Brookings (Aug. 18, 2025), https://www.brookings.edu/articles/how-different-states-are-approaching-ai/ (describing state legislation requiring for consequential decisions in which generative AI is a substantial factor, disclosure and explanation of the technology’s role in decision-making).

[35] See, e.g., Engler, supra note 31 (describing the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation, which prohibits the use of algorithmic systems without human supervision to make significant decisions that affect legal rights, like firing employees).

[36] See, e.g., Desouza, supra note 34 (describing various state legislation limiting and requiring disclosure of generative AI use by local and state government).

[37] See Hardin, supra note 29 at 1247–48 (arguing that choosing to continue the status quo is itself action, such that the advantages and disadvantages of choosing the status quo ought to be weighed just the same as the advantages and disadvantages of disrupting it).