From Consultation to Community-Based Decision Making: How Government Actors Can Drive Inclusive, Effective, and Equitable Community Engagement in Environmental Management

January 29, 2023 by Sy Baker

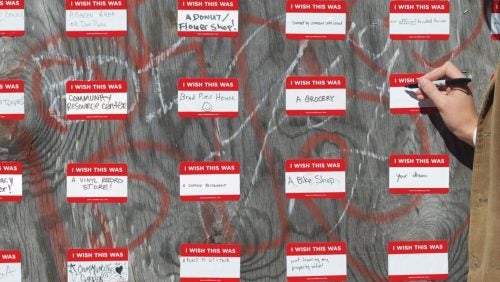

Picture depicting participatory art project developed by artist Candy Chang inviting community members to write in their hopes for abandoned sites. (Candy Chang, 2012)

Community-based decision making in environmental management is making headway in the United States and abroad, presenting a powerful opportunity to increase meaningful public input in environmental management. Yet, to be effective, practitioners seeking to adopt these models must thoroughly assess whether they serve their intended environmental justice and equity goals.

Community involvement in environmental management entails planning related to both the built environment (access to grocery stores, public transportation, and greenspaces) and the natural environment (natural resource management and habitat conservation). Across these different environmental management contexts, there has been movement towards embracing the longstanding efforts of communities already de facto managing environmental resources[1] by delegating decision-making powers previously guarded by governmental entities to the communities that live in and use the environmental resources.

Within these models, the extent to which community members are actively included in the decision-making process varies. The Spectrum of Community Engagement to Ownership presents one framework for understanding the varied goals and methods of these efforts.[2] On one side of the spectrum, the government simply seeks to inform the community of decisions being made.[3] The extent of “community engagement” proceeds from this point to consulting, involving, collaborating, and deferring to community partners.[4] Deferring to community partners involves investments in community-driven planning such as decision-making processes that use consensus building and participatory budgeting.[5]

On the international stage, many countries, like New Zealand, have passed legislation establishing community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) frameworks.[6] These frameworks often involve the community co-developing a resource management plan with government agencies.[7] This model often leads to both more effective management and more equitable development goals for local communities.[8]

Nationally, the Justice40 Initiative illustrates the growing ethos of integrating community input in environmental decision making. Justice40, under President Biden’s Executive Order 14,008,[9] seeks to redistribute forty percent of funding to disadvantaged communities within federal programs that impact the following: climate change, clean energy, clean transportation, housing, workforce development, legacy pollution, and clean water.[10]

Per last year’s Interim Implementation Guidance, programs covered by Justice40 must engage in stakeholder consultation to “ensure public participation and that community stakeholders are meaningfully involved in what constitutes the ‘benefits’ of a program.”[11] This language indicates that community engagement for this policy is primarily at the “consulting” level,[12] rather than requiring more profound involvement of communities. This policy nonetheless represents progress toward recognizing the importance of community involvement.

In recent years, Climate Action Plans (CAPs) have presented an opportunity for community engagement in environmental management at the local level. Today, numerous local jurisdictions produce CAPs, which are roadmaps that cities will take to reduce their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Oftentimes, city governments draw on community input in this Climate Action Planning. For example, in updating their CAP last year, the City of San Leandro, California, utilized 150 in-person and virtual meetings, community workshops, online surveys, and even games to more thoroughly “understand community needs and capacity, identify vulnerabilities and inequities, and build a leadership development infrastructure” for collaboration on climate planning.[13] The extensiveness of this process represents the growing strength and support of community-based decision-making.

However, despite this progress, there is much room for growth for existing community-based models, which are often limited to “stakeholder consultation.” As such, practitioners should consider four initial questions when planning a shift to a more community-based model:

- What support will be offered to the community? At times, community-based programs for environmental management are initially implemented in order to reduce government fiscal responsibility, rather than empower communities. For example, on the international stage, CBNRM was often proposed by international organizations with the initial goal of reducing the financial burdens of environmental management on national governments.[14] While saving money is a potential benefit, this unsupported decentralization has often left communities with few resources to effectively manage the natural resource or derive benefit from the arrangement.[15] As such, when delegating decision making, agencies and organizations should consider what needs the community may have moving forward and how government actors can offer support.

- Do participatory processes use the input generated? There is a real concern that community members might be asked to spend valuable time consulting with an agency, or building management plans alongside it, and that their plans will “sit on a shelf” and the agency will fail to truly integrate the changes sought. Agencies should thus develop metrics to analyze how much community input turns into real decision-making power.

- Are all in the community equally represented? Why or why not? Community management programs may amplify the voices of some in the community and fail to include others, either reflecting or broadening already existing inequities.[16] As such, governments should consider how the decision-making processes that they employ may have unequal outcomes. For example, much has been said about the need to compensate people for their time spent contributing to planning processes, either financially or through skills-based training, to create reciprocity.[17]

- How much real decision-making power is currently delegated, and could there be more delegation? When possible, agencies should consider how they can delegate more decision-making power to community partners to both utilize community expertise in planning decisions and create more equitable outcomes. For instance, Justice40 could use a participatory budgeting framework, akin to that of New York City.[18] This may serve to somewhat democratize the initiative and give voice to the “disadvantaged communities” that this initiative seeks to serve.

[1] See Meghna Agarwala & Joshua R. Ginsberg, Untangling Outcomes of De Jure and De Facto Community-based Management of Natural Resources, 31 Conservation Biology 1232 (2017).

[2] Rosa Gonzalez, The Spectrum of Community Engagement to Ownership, Facilitating Power (2019), https://movementstrategy.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/The-Spectrum-of-Community-Engagement-to-Ownership.pdf.

[3] Id.

[4] Id.

[5] Id.; New York City uses a participatory budgeting model to some extent, where city officials work with residents to brainstorm ideas, develop proposals, and implement a community vote. See Participatory Budgeting, N.Y. City Council, https://council.nyc.gov/pb/ (last visited Jan. 22, 2023).

[6] See, e.g., Marine and Coastal Area Act 2011, s 2 (N.Z.).

[7] See id.

[8] See, e.g., Violeta Gutiérrez-Zamora, The Coloniality of Neoliberal Biopolitics: Mainstreaming Gender in Community Forestry in Oaxaca, Mexico, 126 Geoforum 139, 140 (2002).

[9] Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad, Exec. Order 14,008, 86 Fed. Reg., 7619 (Feb. 1, 2021).

[10] Id.

[11] Memorandum from Shalanda D. Young, Acting Director, Office of Management and Budget, Brenda Mallory, Chair, Council of Environmental Quality & Gina McCarthy, National Climate Advisor to the Heads of Departments and Agencies, Interim Implementation Guidance for the Justice40 Initiative (July 20, 2021), https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/M-21-28.pdf.

[12] Rosa Gonzalez, The Spectrum of Community Engagement to Ownership, Facilitating Power (2019), https://movementstrategy.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/The-Spectrum-of-Community-Engagement-to-Ownership.pdf.

[13] City of San Leandro, Cal., 2021 Climate Action Plan, Res. 21-437 (July 9, 2021), https://www.sanleandro.org/DocumentCenter/View/6490/San-Leandro-CAP-ADOPTED-2021-08-06.

[14] See, e.g., Moira Moeliono, Social Forestry – why and for whom? A comparison of policies in Vietnam and Indonesia, 1 Forest & Soc’y 10 (2017).

[15] Id.

[16] Johanna Kujala et al., Stakeholder Engagement: Past, Present, and Future, 61 Bus. & Soc’y 1136 (2022).

[17] Id. at 1158.

[18] See Participatory Budgeting, N.Y. City Council, https://council.nyc.gov/pb/ (last visited Jan. 22, 2023).