Is a Library-Centric Economy the Answer to Sustainable Living?

October 23, 2023 by Philip Vachon

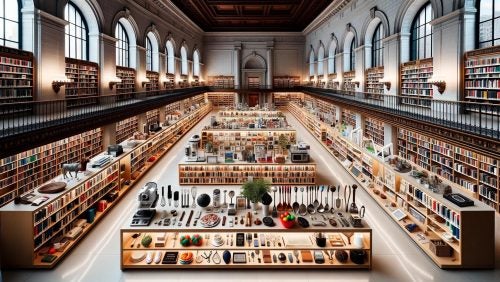

An AI reimagining of the renowned New York Public Library shelved with borrowable tools, cookware, and other amenities.

We need a consumer economy centered around "libraries of things" so we can do more with less.

What would it look like to restructure our economy with the library as its core? That is the question being asked by those in the nascent Library Economy movement. This movement is centered on the idea that building local “libraries of things” is a more sustainable, communal, and equitable way to manage resources in our economy. This would be done by expanding existing library systems as well as incentivizing the creation of non-profit businesses who follow guidelines for libraries of things.

Imagine: your Sunday morning begins with a coffee made in a French press you checked out from the Cookware Library down the block. You may swap it out for a teapot in a couple of weeks. You head out the door with some tennis racquets you borrowed from the Sport & Fitness Library to volley with a friend. Afterwards, you finally get around to hanging those new prints you got from the Art Library and you use tools from the Tool Library to do it. In the evening you checkout a giant Jenga set and an outdoor Bluetooth speaker to bring to your friend’s picnic.

THE FIVE LAWS OF A LIBRARY ECONOMY

Modern library science has five key tenets that would also guide a future library economy. Developed by S. R. Ranganathan in his 1931 book, “Five Laws of Library Science,” these concepts are some of the most influential in today’s library economy. Let’s discuss these laws and how they would apply to the broader library economy.

1. Books are for use

While preservation of certain original works is important, the purpose of a book is to be read. More broadly, a hammer’s purpose is to hammer, a tent to shelter, a children’s toy to be played with. Americans buy a lot of stuff, much of which spends more time idle in storage than in productive use. This law guides libraries to prioritize access, equality of service, and focus on the little things that prevent people from active use of the library’s collection.

2. Every person has their book

This law guides libraries to serve a wide range of patrons and to develop a broad collection to serve a wide variety of needs and wants. The librarian should not be judgmental or prejudiced regarding what specific patrons choose to borrow. This extends to aesthetics of products, ergonomics, accessibility, topics, and the types of products themselves.

3. Every book has its reader

This law states that everything has its place in the library, and guides libraries to keep pieces of the collection, even if only a very small demographic might choose to read them. This prevents a tyranny of the majority in access to resources.

4. Save the time of the reader

This law guides libraries to focus on making resources easy to locate quickly and efficiently. This involves employing systems of categorization that save the time of patrons and library employees.

5. The library is a growing organism

This law posits that libraries should always be growing in the quantity of items in the library and in the collection’s overall quality through gradual replacement and updating as materials are worn down. Growth today can also mean adoption of digital access tools.

ENVIRONMENTAL BENEFITS

The most obvious benefit of a library economy is resource conservation. At the heart of many of our environmental problems is a rate of extraction of raw materials from our earth that exceeds our ability to regenerate. Through the library economy model, it is feasible to decrease the amount of raw materials like metals, minerals, and timber we extract and consume with neutral or positive impact on quality of life. This would have a cascading positive effect on ecosystems, as less land is required for resource extraction and less chemical waste is created in the processes of creating plastics and other synthetic materials.

This model further encourages waste minimization and a circular economy where goods are designed to be reused and recycled. Libraries looking to purchase products for their collection will have the ability to prioritize quality craftsmanship, ethical production, reparability, and durability. This will reward manufacturers and companies who create sturdy and well-made goods while disincentivizing planned obsolescence, throwaway culture, and products that are impossible to repair on one’s own. This will further decrease raw material extraction and will significantly reduce the amount of waste that ends up in landfills, including electronic waste materials that can seriously contaminate nearby soil and water.

Finally, the library economy could significantly lower greenhouse gas emissions by reducing the need for fossil fuels in the manufacturing and transportation of new goods. The industrial sector made up 23% of total U.S. GHG emissions in 2022, and since many industrial processes cannot yet feasibly be done without fossil fuels, it is vital that we find ways to reduce total industrial production.[1]

Real world evidence backs up the intuitive environmental and social benefits of a library economy. The Tool Library in Buffalo, New York, recorded over 14,000 transactions in 2022 and saved the community $580,000 in new products that would have otherwise been purchased for short-term use.[2] The non-profit also partnered with the City of Buffalo Department of Recycling to create pop-up “Repair Cafes” that diverted 4,229 pounds of waste from landfill by teaching residents how to repair their items, demonstrating the potential of complementary programming in library economies .[3] Borrowers at the UK Library of Things have saved more than 110 tons of e-waste from going to landfills, prevented 220 tons of carbon emissions, and saved a total of £600,000 by borrowing rather than buying since the library’s inception in 2014.[4] Information on the storage space, money, and waste saved is made available for each item borrowed.[5] The Turku City Library in Finland even has an electric car available for borrow.[6] In short, people are spending less, doing more, preventing massive amounts of carbon emissions, and reducing the need for needless resource extraction. An expanded nationwide or global library economy would be a multi-faceted boon for the health of the environment.

LEGAL FRAMEWORKS FOR A LIBRARY ECONOMY

Existing law in the United States can enable the development and expansion of a library economy centered around efficient and communal resource management. In fact, limited versions of a library of things are fairly prevalent in existing library systems in many states. In Washington, D.C., the library operates a makerspace where specialized tools like 3D printers and sewing machines can be used but not brought home. The library’s 2022 proposed rulemaking creating a tools library policy, along with its existing makerspace structure, offers a glimpse of the core elements of any library of things’ legal framework.[7] First, waivers are required from all borrowers in order to limit the library’s liability if any injuries or accidents occur while using something from the collection.[8] Release agreements indemnify third parties and include an assumption of risk clause. Second, the proposed tool library policy[9] establishes how borrowing works. The policy is built to incentivize respectful and responsible use of the collection by setting a default borrowing term of seven days, which can be renewed two additional times if the tool is not on hold. The library also lays out a fee structure for late returns or damage to tools. Borrowing privileges are suspended until tools are returned and fees are paid.

The ancient concept of usufruct could also be modernized to manage communal resources like nature areas, fruit and vegetable gardens, or public lands that should be enjoyed by the public without the need of individual waivers and bureaucracy. Usufruct, found in civil law systems, is the “right of enjoying a thing, the property of which is vested in another, and to draw from the same all the profit, utility, and advantage which it may produce, provided it be without altering the substance of the thing.”[10] Legislation creating this limited right for certain communal resources could allow people to eat fruit off of a park tree or utilize fleets of electric cars to profit off of ride-share services, so long as they don’t degrade or overuse the resource such that it is no longer communal or productive. This creates a legal right enforceable by anyone who finds overly extractive resource use occurring.

Additional changes could help institutionalize the library economy. Zoning laws could be revised to allocate public spaces specifically for the purpose of sharing resources. Land use plans could incorporate unique designations for Libraries of Things to ensure accessibility based on proximity to transit, set neighborhood requirements for libraries, or even create library districts in which access to various libraries are centralized. Like all zoning and placement decisions, equity and true community buy-in are essential.

ENSURING EQUITY AND COMMUNITY PARTICIPATION

While the library economy has numerous benefits, it is necessary to address and minimize potential risks. The library economy would prove to be cheaper, but economic justice and racial equity are still serious concerns. A study on Portland, Oregon’s community garden initiative provides an applicable structure to understand barriers to active participation that can inform the specific policies and regulations around the creation of Libraries of Things.[11]

This diagram shows the barriers that researchers found kept community members from participating in the program.[12] These barriers fall into three categories: structural, social, and cultural. Lawmakers, administrators, and staff would be wise to analyze these areas when creating a library and setting relevant guidelines and policies.

Two key issues illustrate the importance of potential barriers and their effect on equity of access and use. First, monetary penalties should be only imposed for very high-value things and should be used with caution. The specter of militant collections or unjust financial penalties could deter borrowing for marginalized groups and the poor, who already know the histories of predatory government fees and fines. Universal participation by communities is essential to avoid perpetuating the ongoing reality in the United States that it is more expensive to be poor and it’s cheaper to be rich.

Second, cultural barriers including language accessibility and a welcoming, diverse staff hired from the community will keep these libraries from becoming the seeds of gentrification. Research from the Portland study showed that lack of inclusionary space was the highest-reported barrier to participation in interviews with residents.[13] The study highlights an example where a community organizer threw a block party at a newly opened community garden and actively invited black community members to celebrate, connect, and learn about the space.[14] This was highly effective in getting community participation and could be a model for library launches.

CONCLUSION

The library economy offers an innovative but familiar approach to resource management. By expanding existing library systems and incentivizing non-profit libraries of things we can address the environmental crisis through legal avenues, fostering a sustainable and equitable future. A library economy will let us do more with less, improve the environment, and possibly make the world a bit more equitable in the process. What will you borrow?

[1] EPA, EPA 430-R-23-002, Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks: 1990–2021 (2023), https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/inventory-us-greenhouse-gas-emissions-and-sinks-1990-2021.

[2] The Tool Library, 2022 Annual Report 3 (2023), https://thetoollibrary.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/TL_AnnualReport_2022_compressed.pdf.

[3] Id. at 11.

[4] Library of Things, https://www.libraryofthings.co.uk (last visited Oct. 21, 2023).

[5] Id.

[6] Turku Abo, Borrow An Electric Car With A Library Card – Turku City Library Makes An Electric Vehicle Available to Everyone, as the First Library in the World, Turku City Leisure Service Bulletin (4.5.2023, 09:00), https://www.epressi.com/tiedotteet/kulttuuri-ja-taide/borrow-an-electric-car-with-a-library-card-turku-city-library-makes-an-electric-vehicle-available-to-everyone-as-the-first-library-in-the-world.html.

[7] Tool Library in the Labs Policy, D.C. Mun. Reg. 19-8 (proposed Sept. 28, 2022) (to be codified at 19 D.C.F.R §823), https://www.dclibrary.org/library-policies/tool-library-labs-policy.

[8] The Labs at DC Public Library, Waiver and Release of Liability, 1https://dcgov.seamlessdocs.com/f/LABSParticipantRelease (last visited Oct. 22, 2023).

[9] Id.

[10] Usufruct, Black’s Law Dictionary (11th ed. 2019).

[11] Jullian Michael Schrup, Barriers to Community Gardening in Portland, OR (Portland State Univ. 2019), https://doi.org/10.15760/honors.786.

[12] Id. at 18.

[13] Id. at 26.

[14] Id. at 34.