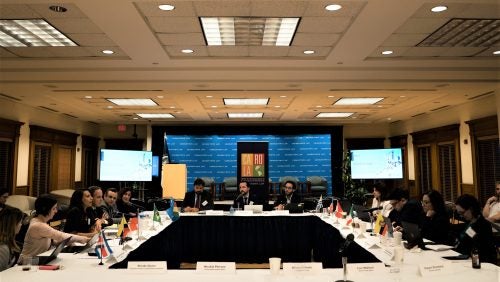

On September 16, 2019, Georgetown Law’s Center for the Advancement of the Rule of Law in the Americas (CAROLA) hosted a one-day conference on “ISDS Reform in Latin America.” The program brought together delegates from Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Mexico, Peru, and Uruguay to share their experiences in the negotiation, administration, and litigation of investment treaties and to identify areas of concern and potential reform. The workshop is part of a broader initiative to provide delegates from Latin American countries a permanent platform for deliberation and regional cooperation as they seek to reform the international investment system. Although workshop discussions were closed-door, a lunch keynote lecture "ISDS and Development: Lessons for a Reform Agenda" with Professor Jeffrey Sachs of Columbia University and a closing session with a presentation of the main workshop conclusions were open to the public.

Workshop on ISDS Reform in Latin America

In recent years, investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) has been at the center of the debate over globalizations’ effects and the entrenchment of corporate power worldwide. As the number of ISDS cases has grown, so too has skepticism over the investment regime’s benefits. Concerns about investors’ power and the reduction of governments’ policy space have emerged, in tandem with incoherent, sometimes contradictory, decisions by investment tribunals. Latin American countries have taken different approaches. For example, as a result of their experiences with ISDS, Argentina, Ecuador, and Uruguay are all currently debating revisions to their treaty models and investment policies to ensure that they pursue the public interest. Colombia’s Constitutional Court recently issued two judgements conditioning the ratification of international investment agreements with France and Israel on the treaties not providing more favorable treatment to foreign investors over national ones. Brazil has so far rejected the ISDS model and instead proposed creating Cooperation and Facilitation Investment Agreements that prioritize inter-governmental cooperation and dispute prevention as a choice to attract and retain investment.

Meanwhile, in the United States, criticism of ISDS has come from both sides of the political spectrum, in voices as diverse as Public Citizen and Cato Institute, the U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer and Senator Elizabeth Warren, and Chief Justice John Roberts and economist Joseph Stiglitz. Opposition to TPP in the U.S., for instance, was largely fueled by the critiques of ISDS. Additionally, as emerging economies now account for more than half of global foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows and almost one third of outflows, rich countries are increasingly concerned about the system’s restrictions on their own regulatory space.

Against the backdrop of the ISDS backlash, a number of proposals for reform have begun to surface. The European Union and international institutions such as UNCITRAL and UNCTAD are leading the agenda for reform. At CAROLA, we would like to explore how the international investment regime could be reshaped from the global south, reflecting the interests of developing countries, and in particular of Latin America. What has been the experience of Latin American countries with ISDS? What version of international investment ordering are countries in Latin America interested in pursuing? Is there enough common ground between the nations of the region to follow a unified agenda for reform? Capitalizing on the momentum generated by UNCITRAL’s Working Group III October 2019 meeting on Investor-State Dispute Settlement Reform, CAROLA seeks to provide a platform for Latin American stakeholders to discuss these questions.

Workshop Conclusions

The group reached five conclusions on which there was general agreement:

- With the exception of Brazil (country that would prefer no version of ISDS), there is consensus on procedural aspects that need reform. They include reforms pertaining to arbitral awards, the conduct of arbitrators, and the duration of proceedings, all of which fall squarely in the agenda of UNCITRAL and should be “early harvests.” There is also consensus that a comprehensive agenda for reform would eventually need to take account of substantive issues as well.

- A multilateral mechanism for reform would be desirable. In this regard, Colombia’s submission to the 38th session of UNCITRAL’s WG III proposes a multilateral convention and points to the OECD’s BEPS Multilateral Tax Convention and the Mauritius Convention on Transparency as possible models. The virtue of a multilateral instrument of this type is that it offers countries the possibility to reform their network of investment treaties simultaneously rather than bilaterally and one-by-one.

- Delegates emphasized the importance of “flexibility” in the reform process, so that it can proceed at a pace and on the subject-matters that respond to each country’s needs. A multilateral mechanism for reform like the one discussed in the workshop incorporates this principle of flexibility.

- There is strong interest in dispute prevention and in amicable resolution of disputes as a key element of reform. Delegates took notice of Brazil’s approach, which has made these principles central to its strategy of attraction and retention of foreign direct investment. Brazil will continue to engage with the group and support discussions while continuing to follow its own approach.

- Delegates discussed the desirability for a review mechanism of arbitral awards but did not agree on any one mechanism or format.