Disney, NBC Universal, and DreamWorks File Major IP Lawsuit Against AI Image Generator Midjourney

June 24, 2025

Matthew Sparks

The intellectual property world’s most notorious litigator has joined forces with two of its arch-rivals to bring another legal challenge to generative AI’s use of copyrighted material, alleging that a major AI image generator has engaged in mass copyright infringement.

Bottom Line: With the filing of this lawsuit, Disney and Universal have opened up another front in major IP holders’ war to rein in generative AI’s use of their property as training data. Additionally, this lawsuit marks the first time that major Hollywood studios have sued AI companies.

Analysis

On June 11, Disney, NBC Universal, and DreamWorks filed a major copyright infringement lawsuit against AI image-generation company Midjourney, alleging mass infringement of the companies’ intellectual properties. The companies seek injunctive relief barring Midjourney from offering its imagegeneration services without the implementation of copyright protections preventing the reproduction of the plaintiffs’ IP. If granted by the court, this would effectively force at least a temporary shutdown of the entire Midjourney service. Midjourney, however, is likely to fight these claims in court.

In a 110-page complaint (link to PDF) filed in federal court in the Central District of California, the plaintiffs make the case that Midjourney, whose site allows users to create AI-generated images based on written prompts, has effectively engaged in mass piracy of Disney, Universal, and DreamWorks’ IP, and used said IP as training data. The complaint does not mince words:

“…Midjourney is the quintessential copyright free-rider and a bottomless pit of plagiarism. Piracy is piracy, and whether an infringing image or video is made with AI or another technology does not make it any less infringing.”

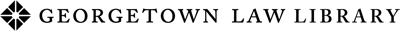

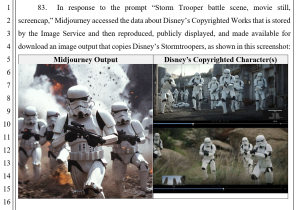

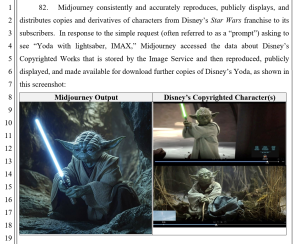

The plaintiffs further allege, with numerous examples, that Midjourney has done this to such an extent that the image generator can reliably generate downloadable, high-quality images of copyrighted characters that are nearly indistinguishable from official artwork.

The plaintiffs underscore the fact that Midjourney is consistently capable of generating images of specifically named characters. That is to say, as shown in the example above, the AI is willing to produce fairly realistic depictions of Star Wars character Yoda in response to the prompt “Yoda with lightsaber, IMAX,” (a prompt which contains no fewer than three copyrighted or trademarked phrases). The user need not engage in any circumlocution or prompt engineering.

The plaintiffs additionally show the AI’s ability to replicate specific scenes and frames from particular movies with remarkable accuracy. To be fair, it is possible that at least some of Midjourney’s output is attributable to the thousands of media articles covering Avengers: Infinity War, many of which likely used the same (or similar) promotional stills from the movie. Yet, this would probably still constitute a misuse of Marvel’s IP.

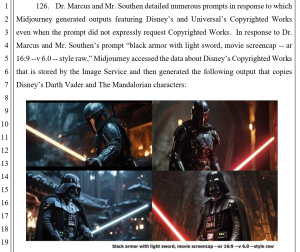

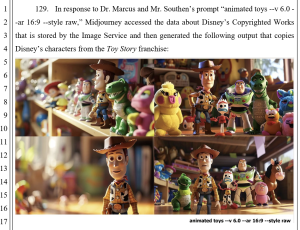

Perhaps the most damning part of the plaintiffs’ accusations, however, is that Midjourney is capable of generating highly realistic depictions of copyrighted characters without being instructed to do so. While some of the prompts shown in the complaint are fairly specific – for instance, “black armor with light sword” or “man in robes with light sword,” others are exceptionally generic “animated toys” or “popular movie screencap,” and yet result in exceptionally specific depictions of copyrighted characters.

GenAI vs. IP Law: The State of Play

The generative AI field is already fighting multiple major IP lawsuits. Two of these are especially noteworthy:

New York Times v. Microsoft

Of these, the most reported-on is undoubtedly New York Times v. Microsoft in the federal Southern District of New York, in which a coalition of newspapers and publishing companies are suing Microsoft and OpenAI for alleged mass infringement of their written material. The defendants, for their part, argue that training data falls under the category of “fair use” under U.S. copyright law. Though filed in 2023, the case still has yet to go to trial, as the litigants have been mired in pre-trial procedural issues and discovery requests. This case poses a very real risk to the OpenAI and Microsoft’s businesses, as the remedy requested by the plaintiffs includes (potentially) a court-ordered shutdown of GPT-4, as well as all other OpenAI and Microsoft LLMs which have used the plaintiffs’ works as training data.

Getty Images v. Stability AI

The other major case pitting generative AI against intellectual property rights is Getty Images v. Stability AI, filed in the federal District of Delaware. In this case, stock photo owner Getty Images has sued AI image generator StableDiffusion for allegedly using Getty’s proprietary stock photos as training data. In legal terms, this case is largely similar to New York Times, except it applies the same reasoning (training data as not constituting “fair use”) to images (along with image metadata and captions), as opposed to text. The other main difference between Getty Images and New York Times is that Getty is additionally pursuing a trademark infringement claim, owing to the fact that the StableDiffusion AI has, on occasion, reproduced the Getty Images watermark. (This is significant because trademark infringement, in which one company passes off its products as those of another company, is a significantly more serious intellectual property violation than copyright infringement, and allows the plaintiff to seek triple damages.) Getty’s requested damages, amounting to over $1 billion, would likely bankrupt Stability AI.

Where does the Disney lawsuit fit in?

In terms of the law itself, Disney’s lawsuit has far more in common with Getty Images – both suits deal with visual media as opposed to the written word, and, as such, hinge on the same legal issues.

However, in some ways, the Disney lawsuit is potentially much more compelling (and, arguably, dangerous for the AI industry) than either New York Times or Getty. In the NYT case, while the full, unaltered text of copyrighted written works can be regurgitated by GPT-4, doing so requires a bit of prompt engineering (specifically, pasting parts of the text of a given written work into ChatGPT, causing ChatGPT to supply the remainder of the text.) Midjourney, by contrast, will readily generate images of copyrighted characters by name. That is, a user need only prompt the AI with “Yoda,” and not, say, “a short, elderly, green, humanoid alien with pointed ears dressed in a brown robe and carrying a laser sword.” It would, indeed, appear that Midjourney has no internal protocols intended to prevent such use of the platform.

Additionally, the Disney lawsuit has something else working in its favor: pictures. The saying “a picture is worth a thousand words” exists for a reason, as humans tend to find visual media inherently compelling. Disney and the other plaintiffs thus have a powerful weapon in their arsenal—the ability to show a court (and a jury) images of alleged infringement, rather than simply text excerpts.

Compared to the Getty lawsuit, Disney’s case also has some critical advantages. The reason for this is the subject matter. Getty deals with stock photos – images which are, by design, so generic as to be fundamentally unremarkable. The Disney case, by contrast, deals with highly recognizable popculture icons. This is beneficial, because it makes the subject matter much more recognizable, and also makes the degree of Midjourney’s mimicry all the more evident.

Should we have seen this coming?

It was, frankly, almost inevitable that Disney would eventually step into the ring with a generative AI platform. Disney has a well-earned reputation as one of the most dreaded and aggressive IP litigants in existence. This is for two reasons.

First, Disney is, to put it bluntly, a cultural powerhouse, with a portfolio so broad as to border on monopolistic. Aside from its original IPs like Mickey Mouse, the company owns a vast array of other highvalue properties across various genres, including the Star Wars franchise, the Marvel Cinematic Universe, Pixar Studios’ films, Avatar, Indiana Jones, Pirates of the Caribbean, and countless others. Along with this, Disney has acquired 20th Century Studios (formerly 20th Century Fox), including with its entire catalog of films and TV shows stretching back to the 1930s, as well as indie film distributor Searchlight Pictures. The company is also the owner of National Geographic and its documentary programming, and is the majority stakeholder in sports broadcasting giant ESPN, which itself holds the broadcast rights for countless sporting events. Finally, the company has also become a major player in the streaming space, with the launch of its Disney Plus service. All in all, Disney has a staggering number of properties on which it can make IPrelated claims.

The second reason Disney has this well-earned reputation is the way it protects these IPs—extremely proactively. The company is known for not hesitating to send “cease and desist” notices or threaten litigation against threats to its IPs, real or perceived. This policy has traditionally been enforced in an extremely strict manner.

Disney is, indeed, quite notorious for issuing legal threats over even relatively minor or small-scale uses of its IP. In 1989, the company threatened to sue three Florida day-care centers for painting likenesses of copyrighted Disney characters on their walls as decoration. Disney arch-rival Universal, smelling a minor PR coup, swept in and offered the day-cares the rights to use Universal Studios characters instead. Ultimately, no legal action occurred, as the Disney characters were quickly replaced with Universal characters, rendering the matter moot.

In 2020, the company attempted to charge an elementary school’s parent-teacher association $250 for holding an unauthorized screening of The Lion King as a fundraiser. Uncharacteristically, the company ultimately reversed course, with CEO Bob Iget ultimately apologizing for the incident.

By far, however, the most infamous case of Disney’s aggressive protection of its IP came in 2019, when the company’s legal representatives denied a grieving family in the UK permission to place an image of SpiderMan on their deceased 4-year-old’s tombstone, citing a company rule apparently promulgated by Walt Disney himself. The company ultimately ordered the family to remove an image of the character from their child’s grave.

Why Midjourney?

Simply put, Midjourney posed an almost-perfect target for Disney’s lawsuit. To begin with, the two other giants of the AI image-generation world, Stability AI and OpenAI, are both already embroiled in IP litigation of their own. Since those suits are already much further along in the litigation process, this would leave Disney with the company’s financial leftovers if it prevailed and received damages. Midjourney, however, has managed to avoid any major IP suits up to this point, while still bringing in enough revenue (around $200 million) to at least be able to pay the plaintiff’s attorneys’ fees if it loses. Thus, the focus here is probably not so much Midjourney’s specific actions as it is the actions of AI as a whole. Indeed, Disney’s General Counsel has suggested as much, stating that “[t]his is our first case, but it likely won’t be the last.”

The real motive for Disney here is not money – at least, not directly. Rather, it is the preservation of the legal principles upon which the company’s business model depends. It is not without good reason that the company has joined forces with two of its most bitter arch-rivals to defend their collective intellectual properties. Generative AI, and especially generative video AI (a version of which was just launched by Midjourney, only days after the filing of the lawsuit), pose a massive, and potentially existential threat to Hollywood studios and creatives. The objective here, like in the New York Times case, seems to be to set a precedent for the entire AI industry, and ensure that it is one which protects the rights of intellectual property holders.

Matthew Sparks was a Justice Fellow at the Tech Institute 2023-2024.