Celebrating Georgetown Law Professor Ladislas Orsy, S.J. — at 96 Years Young

January 23, 2018

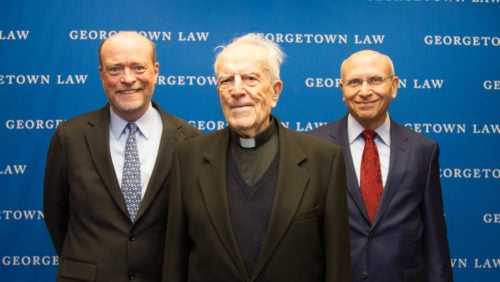

Georgetown Law Dean William M. Treanor, Visiting Professor Ladislas Orsy, S.J., and Professor David Luban at a January 24 conference celebrating the 96-year-old Orsy's life and work.

The polarities between political parties are not fundamentally different than those between Plato and Aristotle, according to Visiting Professor Ladislas (“Les”) Orsy, S.J.

One side, like Plato, dreams of a utopia with many kings — creating jobs for others. The other side, like Aristotle, seeks a redistribution of wealth.

“Everything that has happened ever since Aristotle and Plato is a struggle between those two,” explains Father Orsy, who spent part of December grading exams for the 20 students in his Fall 2017 “Great Philosophers on Law, Human Rights and Obligations” class.

“The ideal socialist regime in Russia was a dream where everybody’s happy, everyone has everything,” he says. “But so many ended up in misery. Western democracies relied more on experience. You can see those two inspirations today in modern political parties, even in Congress. There is an ongoing conflict. Aristotle says that when somebody gets very rich, the state has to intervene and make sure that what is superfluous for him is fairly distributed among the others. He was not against competition, but up to a point.”

New discoveries

At the age of 96, Father Orsy is gearing up to teach two courses in Spring 2018: one on Roman Law and one on the role of the Vatican and the Holy See in international law, looking at their relationships to the United Nations.

But don’t even think that Orsy — who joined the Georgetown Law faculty in Fall 1994 at the age of 73 after (supposedly) retiring from Catholic University — is just dusting off ancient texts and syllabi. “You see this?” he says, indicating an impressive collection of materials for his philosophy class. “These are the handouts, but the handouts change always; what was there five years ago is not what is there now. There are new discoveries.”

His spring course on the Vatican City State and the Holy See, in fact, is a completely new class. “The Holy See is accepted by the UN as an international corporation, not as a state…a corporation that happens to be religious,” Orsy explains. “It has the status of a privileged observer. On some issues it can vote, but never on political issues. Otherwise it has virtually identical or similar rights as states—voting on the protection of children, protection of women.”

Vision

And on January 24, Georgetown Law will host “Vision, Law and Human Rights, A Celebration of the Work of Professor Ladislas Orsy, S.J.” Professors David Luban, Robin West and Naomi Mezey will host a lineup of philosophers, theologians, lawyers and human rights advocates to examine Orsy’s scholarship on Vatican II, canon law and international human rights — as well as his life as a professor, lawyer and priest.

Orsy, who grew up in Hungary, entered the Society of Jesus in 1943. He was ordained to the priesthood in Louvain, Belgium, in 1951 and came to the United States in 1966. In the meantime, he earned at M.A. in Law at Oxford University (the equivalent of a J.D. in the United States) and a doctor of canon law at Gregorian University in Rome. He also earned degrees in philosophy and theology in Rome and Leuven, Belgium, allowing him to teach at Catholic universities worldwide. He taught at Gregorian, Fordham and Catholic University before landing at Georgetown Law.

In anticipation of the upcoming conference, we sat down with him to talk about philosophy, religion, writing and teaching over the course of his long career.

Let’s start with your background — you grew up in Hungary?

I did all my first studies from elementary school to high school, and first years of university, in Hungary. I was born in Egres, but the place I [grew up] and as it were, marked my life, was Szekesfehervar, an ancient city, a thousand years old, originally the capital of Hungary, and the great kings of Hungary reigned from there. The English translation is “Royal White Fort,” because it was a fortress in those days and it was the capital city for over three hundred years. I grew up surrounded by the ancient ruins of buildings and it gave me a perspective on history. Every day you are walking by the foundations of a basilica built a thousand years ago. And it shapes you. Parts of the old walls are still there.

Did you envision yourself as a teacher, lawyer, priest?

I enjoyed what I was doing [in school]. Of course, various ideas and images ran through my mind. But I was not one of those who from the age of 10 discovered my future profession. That was later on.

How did each one of these life events come about? What came first?

I joined the Jesuits in 1943, when I was studying [in college]. I liked the work of the Jesuits. They did campus ministries at the university, publications. I always liked literature and I was a fledgling writer. This was the starting point.

This was during World War II…

The war reached us, believe it or not, on Christmas Eve, 1943; the Soviet army arrived in the house where I was.

What kind of work were the Jesuits doing in Hungary?

About the same as here. They had schools and they did a lot of publishing, they did a lot of preaching. At that point, there was no firm planning about what I was going to do. I was going into the basic training for the Jesuits.

And your studies?

I studied philosophy in Rome, then undertook my theology studies in Leuven, Belgium; that’s where I got my degrees. I reached Rome in 1946, one year after the war ended, and there was a great poverty in the city. People were taking shelter in old ruins. But the recovery was extremely swift.

How did you get involved in the law?

I was already doing some legal studies in Hungary, and [the Jesuits] simply needed people to teach. They needed to train lawyers — they have a faculty of church law, canon law, in Rome and they needed people for that. They asked me if I would take on that job.

Did you envision where it was going to take you?

No. The world was very unsettled. You could not plan with much certainty. In general, the intent was that I should be in Rome and teach at the Jesuit university. That was certainly contemplated as one of the possibilities, but not exclusively.

Then you got a degree in law from Oxford…

That had an impact on the way I think…it was very different from everything else I had known. They have three terms, not semesters. You arrive and you are assigned to a tutor who takes you through that semester and as a rule, within the semester you are taking all of the principal subjects under that tutor. They want to bring out any creativity that may be in you by compelling you to produce an essay every week. And then the tutor is bound to spend one hour with you over that essay every week.

How did you get to the United States?

I came to the United States in 1966 — I was already teaching in Rome in the faculty of canon law of Gregorian University. The first step was an invitation from the Catholic University here, to come over as a visiting professor for a year. And while I was here, I got a [permanent] invitation from Fordham. Then Catholic University wanted me back.

What made you decide to come to Georgetown?

[Former Dean] Judy Areen invited me. I was at Catholic University and in 1991, I reached the age of 70. At that time it was compulsory to retire, and because I joined the New York Jesuits, I packed up everything and went up to New York. I was asking myself what to do now, and I got a phone call from Judy Areen. She knew me, because earlier [Georgetown Law] deans had invited me to be a visiting lecturer. And [I’ve been here] ever since.

I started teaching canon law, but I noticed different things about the students, their interests. I had other interests as well. The [subject] into which I drifted was the history of philosophy of law, because that reaches very far and touches the whole culture. It was interesting for me to see the European cultural context in which I was educated, and compare it to the American cultural context, albeit within a university, albeit on a broader scale — to think about it, speak about it.

You have been teaching the Great Philosophers of Law seminar for 20 years. How do you make it relevant to students today?

My courses are introductions into a new field: philosophy of law and also Roman Law. With Great Philosophers, I make them confront philosophers of antiquity and philosophers of modernity. I begin with Socrates and Plato and I try to bring them to a point where they achieve at least a partial understanding of the main points of their philosophy. It’s not difficult to understand a philosopher if you know how they started out thinking and where from. You have to work as a detective. They lay down the foundations and on that foundation they build a complicated system. In universities, that’s what they tell you, [the system]. It’s like taking you to the Capitol and showing you the dome and the meeting chambers but never showing you the foundations. Once you have seen the foundations, you can understand what can be built and what cannot be built — what you can expect and what you cannot expect.

How and why did you get interested in human rights?

Partly because it was in the air. Here, and everywhere. The students have an interest in it — I am trying to enter into their world by a door that they have opened. They are very open if you begin to speak about human rights… In Rome, in the third century before Christ, they set up a new court to take care of foreigners — any foreigners, because it was becoming a worldwide city with commerce going through it. And any foreigner, irrespective of color or nationality, had a right to approach the tribunal if they had suffered any kind of injury — anybody could do that. The community has a duty and obligation to protect citizens and foreigners equally. It was a special court for that.

What fires you up about teaching?

The shaping of the minds — much more than conveying the knowledge. Which is necessary, but one day you leave this place. What kinds of minds do they carry with them? Is it an open mind? Is it a creative mind? With myself, I go through it [indicating syllabus]. The handouts keep changing always. The gist of it remains the same.

The conference on January 24 will talk about your scholarship regarding the Vatican II Council in the 1960s. [Father Orsy was present for the preparation of a new Code of Canon Law that was written at the time and took effect in the 1980s.] Is there anything that you want to say about Vatican II?

It was, and remains, a good part of my work. I published a couple of books on it. The issue was setting a new course for the church for the coming decades or maybe centuries. It was an interesting event because you had over two thousand bishops there from all over the earth and peacefully and quietly agreeing to a number of things. At that time I was teaching in Rome, from 1960 to 1966. Because I was teaching at the Vatican University I consulted with the bishops and knew the papers.

You have published nine books?

Something like that. [And hundreds of scholarly articles].

Are you looking forward to the conference?

Yes. With all praise to those who are organizing it, I would have liked a good debate [but Father Orsy will of course be responding to the panelists, in a good conversation.]

Read about the conference honoring Father Orsy in the National Catholic Reporter.