Professor Abbe Smith on Jail Conditions amidst COVID-19, Teaching Criminal Defense and Her New Book, “Guilty People”

April 2, 2020

Professor Abbe Smith

Criminal defense lawyers “see the ravages of poverty, inequality, and mass incarceration up close,” Professor Abbe Smith writes in her latest book, Guilty People (Rutgers Univ. Press).

Today, as COVID-19 threatens the nation’s prisons and jails with a potentially massive public health crisis, Smith answered questions about the criminal justice system’s response to the pandemic, her book, and her work leading Georgetown Law’s Criminal Defense and Prisoner Advocacy Clinic and co-directing the E. Barrett Prettyman Fellowship program.

Do you feel that the nation’s correction officials are responding with proper urgency to the pandemic? What steps would you like to see?

Smith: No, I don’t, which is disappointing. I thought this might be a moment of common ground for the incarcerated and those who guard them, as both inmates and correctional officers are essentially living in the same dangerous place. Second only to nursing homes, jails and prisons are incubators for disease. But law enforcement in general seems to be resisting release of significant numbers of inmates. At best those who will be released will be the “usual suspects” of criminal punishment reform, or what scholar Marie Gottschalk calls the “non, non, nons” – non-serious, nonviolent, non-sexual offenders.

Corrections officials don’t have a lot of power compared to others in the criminal legal system, but they could insist that prisons and jails have working sinks, soap readily available, other hand sanitizer dispensers throughout the institution, disinfectant for surfaces in cells and common areas, increased infirmary beds for those with coronavirus – quarantined in a separate part of the infirmary – more medical resources and staff, and protocols for social distancing, including no double or triple bunking in cells.

The United States has a large population of older inmates. Because of their age, they face greater risks with the pandemic. What can be done for them?

Smith: We have a serious aging prisoner problem in this country because of the policies that gave rise to mass incarceration. In the past 30 years, more people are serving more time than ever before. The lifers at Jessup Correctional Institution [in Maryland] to whom clinic students teach legal research and writing are mostly middle-aged and older, and a couple of older men use either a walker or a wheelchair. We should be releasing older prisoners who have served decades in prison, have grown and changed, pose no risk of danger to anyone, and will likely die in prison.

We need to take a page from other western democracies and recalibrate sentencing practices. We also need to acknowledge what social science has shown: people age out of crime. Moreover, in those jurisdictions that have released people from jail and prison due to COVID-19, there has apparently been no uptick in crime.

Is there anything ordinary citizens can do to help avert this crisis?

Smith: Write to your state and local elected officials, including the governor of your state. Most prisoners in this country are in state and local jails and prisons. Write to members of Congress and maybe Jared Kushner—he was behind the First Step Act, which led to the release of some federal prisoners—about those in federal facilities.

How is the clinic operating and serving your clients during this time? Are cases being put on hold? How do you continue to represent clients while also practicing social distancing?

Smith: All cases have been rescheduled for May, including those of detained clients. Who knows what will happen in May and how many cases will actually go forward then. We are doing the best we can to try to get people out of jail and prison. Our misdemeanor clinic clients—represented by students and fellows under faculty supervision—are mostly, but not entirely, out of jail. Our felony clients—represented by fellows under faculty supervision—pose a greater challenge. Some are out but many are not. It is very difficult to represent people in jail under these circumstances.

We were going to the jail until very recently. But there have now been reported cases of coronavirus in both the Central Detention Facility and the Correctional Treatment Facility of the DC Jail. We can’t send students there. I expect that the fellows and faculty will go to the jail when we need to in order to effectively represent our clients. We are relying on old-fashioned letter writing and trying to arrange phone calls with clients who are locked up.

Sadly, we are not allowed in either of the two maximum security prisons in Maryland where we teach legal research and writing during the pandemic. We are doing our best to continue these classes by sending teaching materials and providing feedback on written materials through the mail.

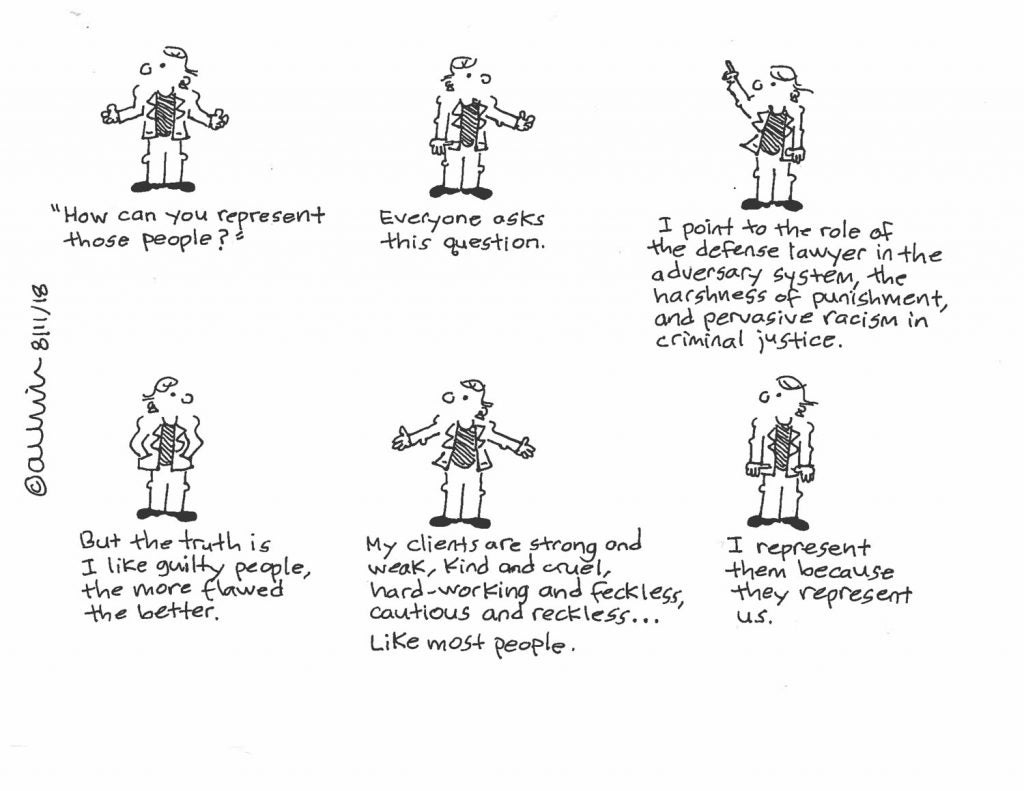

In your book’s introduction, you write, “The truth is, I like guilty people.” What do you most hope to get across to your readers?

Smith: Guilty People is about the humanity of my clients – whether they’re petty criminals, murderers, or something in between — and the absurdity of the criminal legal system.

I do a little exercise every time I have a chance to talk to young people about criminal defense. I pass out index cards, and I ask the students or the interns to write on the index card the worst, most shameful thing they’ve ever done. I assure them nobody will see what they’ve written and they should turn it over as soon as they’ve written it, and after this exercise, they can tear it up. I say, now imagine that what you’ve written on that card is all anybody ever thinks about you. Not your sparkling personality, not your generosity to friends, not your various talents, interests, not how you see your future, not the impact you want to have on the world. But just what you wrote on that card.

It’s not a very subtle exercise. But that’s how my clients feel. They feel that they’re reduced suddenly to this one thing. So I suggest that we all have regrets, and if we’re lucky, we get second chances. My clients very seldom do.

In your book you say a combination of three things keep long-term defenders going: respect for the client, dedication to professional craft, and a powerful sense of outrage. How do you teach these things?

Smith: Spending any amount of time in poor people’s courts develops outrage in anybody who’s paying attention because the outrages just keep coming: the unfairness, the inequality, the very limited access to justice.

Respect is part of teaching counseling, in particular. One of the things I try to teach students and fellows is when you meet a client and you introduce yourself, one of the most important things you can say to a client is, “I work for you.” Also, our clients experience so little respect in their lives. It’s important for the lawyers to at least show that respect.

Craft runs the gamut. Craft is everything from learning how to be a good trial lawyer: skills of advocacy which include the ability to give a good opening statement, to conduct a cross-examination that’s effective, a direct examination that’s effective, to make good legal argument, to give a passionate and convincing closing argument. It also includes the skills of interviewing and counseling, negotiation, creative motions practice, and creative trial theories.

Criminal defense lawyering is intensely inventive. I often say to students and fellows, the job of a criminal defense lawyer is either to make nothing of something or something of nothing. There’s a little magic in there; there’s a lot of creativity. We are storytellers at our best.

In the last chapter, you focus on criminal defense lawyers and discuss a trend toward martyrdom in the profession. You say the “image of the public defender as all-sacrificing and long-suffering” is not a good thing.” Why?

Smith: I have a not-very-subtle agenda in being a clinical law teacher: I mean to create public defenders. I mean to draw people to this work and to enable them to do it for the long haul. I don’t think it’s helpful to have people who are public defenders for three years, are very good at it, give it their all, and then, at the point at which they’ve developed some expertise, leave because they’re burned out. Offices suffer when there’s too much attrition.

I realize that doing this work for the long haul is not for everyone. I also realize that criminal defense is not for everyone. But part of the craft I’m interested in teaching is sustaining a career in indigent criminal defense. I want to give people the tools to hang in there.

Have a lot of clinic students gone on to long careers in criminal defense?

Smith: So far, so good. Increasingly, the students who take the Criminal Defense and Prisoner Advocacy clinic are committed defenders. I feel really lucky. Some of the students in the clinic are as talented as anybody I’ve ever had in the fellowship program. I would say that lately, in the past ten years, the vast majority of my clinic students go on to public defender offices and most are still there.

One of my favorite former students, Alaric Piette, who was a Navy SEAL, is now representing the person accused of the U.S.S. Cole bombing. He came to law school thinking he might want to be a prosecutor, and I’m proud to say he took the criminal defense clinic and decided, he’s kind of a natural defense lawyer.

One of the most moving things he says when people ask him is: How can you go from being a Navy SEAL to representing someone who’s accused of bombing a Naval ship? He says, “Here’s the thing: when I joined the Navy as a young man out of a small town in Wisconsin, I swore to uphold the Constitution of the United States. And now as a criminal defense lawyer, I swear to uphold the Constitution of the United States. It feels the same.” I find that so powerful. I’m so proud of him.

The book includes a handful of your very wry cartoons. What’s the story there?

Smith: I’m really happy about the cartoons. I’m an erstwhile cartoonist. I was a cartoonist for the Yale Daily News in college and also for my law school newspaper. I have had cartoons published in a bunch of places, including Ms. Magazine and I had a book of cartoons published when I was a public defender called Carried Away: The Chronicles of a Feminist Cartoonist. This was kind of a dream – to have a book that included my cartoons. One of the things that makes me really happy about this book is that I finally accomplished that.

Watch a video of Professor Abbe Smith explaining why she chose a career defending the guilty: