1Ls Build Practical Skills Early with Week One Simulations

January 13, 2019

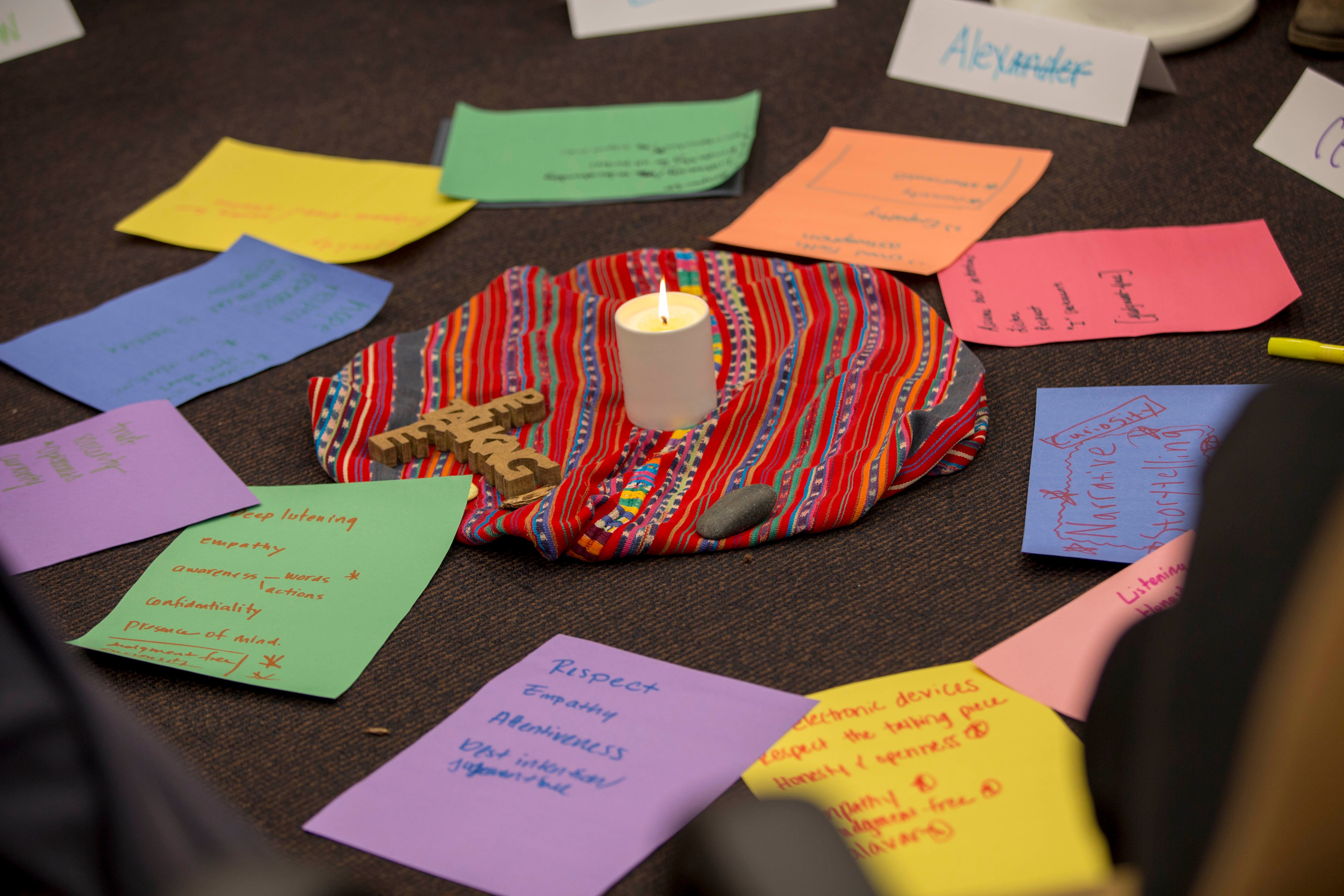

Georgetown Law 1Ls in Professor Thalia Gonzalez's “Restorative Justice” class participate in a talking circle during Week One. Week One classes are developed by Georgetown Law faculty to mirror situations that lawyers may face in the real world, from conflict resolution to teambuilding.

One week into the new year, Georgetown Law students sat in a rearranged classroom, in two concentric circles. In the center, the flame of a small candle flickered on the floor, surrounded by a wooden elephant from India, a frisbee, a running shoe, a ring from Rwanda made from melted down padlocks, a family photo and a watch.

Thalia González, a senior visiting scholar at the Law Center’s Center on Poverty and Inequality, had brought the candle and a quote to share.

“It says that peace is not a moment without tension, concern and noise,” she said. “It’s finding that moment despite all those  things. Law school is a place of competing ideas and frustration, and it can be messy and loud. But making time and space for peace is really important.”

things. Law school is a place of competing ideas and frustration, and it can be messy and loud. But making time and space for peace is really important.”

The students around González were gathered in a talking circle, the most widely used model of restorative justice in the U.S., designed to help participants explore a particular issue from multiple perspectives and think about human relationships in new ways.

The class, “Restorative Justice,” offered at the Law Center for the first time this year, was among the elective courses offered during Week One, a one-credit, optional four-day mini-session held every January before the spring semester.

Fast-paced introductions

The courses for first-year students, largely simulations, are developed by Georgetown Law faculty to mirror situations that lawyers may face in the real world, from conflict resolution to teambuilding. They serve as fast-paced introductions to experiential learning and—because they are pass/fail—offer a supportive environment in which students can make mistakes and receive immediate feedback.

González, who sat in the inner circle of 10 students and teaching fellows as the outer circle of students observed, passed a small grey stone with “COURAGE” written on it to a student sitting to her right. One by one, with the pass of the stone, each spoke about the possession they had been asked to bring that day and why it was important to them.

When the talking piece reached Alex Bodaken (L’21), he held up his frisbee and explained how ultimate frisbee, a sport that keeps him grounded, is self-officiated. “A lot of the values are the same as those we have in the circle,” he said. “You have to respect each other and assume best intentions.”

González’s course attracted a diverse group of 1Ls, including a former Politico reporter, Peace Corps volunteer and researcher-turned-novelist. Many said they were drawn to the class to learn about this alternative form of conflict resolution that reduces recidivism and addresses issues through dialogue and problem-solving. Restorative justice also leads to increased emotional literacy, social connectedness and victim satisfaction, González said. During the week, students participated in a simulation around a first-time juvenile shoplifting case for which the restorative process was a community harm-repair circle.

“Increasingly in the United States as lawyers, you will come in contact with restorative justice, and it’s important to know what it is,” González told the students during the first hour of the class. “Is it a principle? A practice? A project? A program?” She explained that it’s different from negotiation and mediation, and while restorative justice not a typical law school subject, it’s important for law students to learn because it cuts across so many communities, including law enforcement, schools and child welfare.

González, also an associate professor at Occidental College in Los Angeles, said restorative justice’s roots go back to the 1970s, with victim offender mediation. Today, 45 states have nearly 300 restorative justice laws.

Learning to listen

González told the students that lawyers tend to think they’re good listeners, but restorative justice can challenge listening competency at a higher level. “Learning to listen deeply—and then learning to synthesize that information together in a holistic way—is an incredibly difficult skill,” she said.

Much of the time spent in a circle focuses on relationship- and trust-building, which require deep listening. After students agreed on values and guidelines for their circle, González asked them a variety of questions. Who or what makes them laugh? How they would spend 24 free hours? What they would title their autobiography and what brought them to law school?

In the last phase, González asked for three talking rounds, addressing why law school’s great, why it’s difficult and what students could to do better support themselves or others in school.

Bodaken, the ultimate-frisbee player, said he never expected to experience anything like a talking circle in law school. “1L is very much reading old opinions—which are important—but it’s not a lot of learning about what the law could be or should be,” he said. “These are interesting questions you don’t normally get to explore as a first-year law student.”

How to investigate, litigate and regulate

Other Week One simulation courses covered evaluating corporate corruption, internet defamation, designing post-crisis financial regulation and social intelligence in dealing with clients, colleagues and opposing counsel.

Students in the “Internal Investigation Simulation: Evaluating Corporate Corruption” class role-played lawyers investigating a French pharmaceutical company. The company, listed on the U.S. stock exchange, has discovered evidence of bribe-like payments made to a charity linked to government officials as part of its operations in Africa.

Students interviewed key witnesses and assessed the risks posed to their clients under the provisions of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA). The simulation was designed with enough characters that the students lost track of them at times—simulating real life.

Professor Michael Cedrone explained that there were a lot of grey areas in the case. “The bribe is not a suitcase full of money handed to the minister of health,” he said. “You don’t need a course for that. But how about a donation to your favorite charity? We’re teaching them to learn and act in areas in which they have a lot of legal and factual uncertainty.”

Practical professional skills

Cedrone, who has taught this class for five years (professors Erin Carroll and Susan McMahon taught other sections of the course), said Week One is the first opportunity for 1Ls to learn practical professional skills. His course exposes them to areas such as interviewing and client counseling, speaking to a client (and deciding how much detail he or she needs) and the critical skill of delivering bad news to a client.

Students take ownership of their learning, said Cedrone. “I coach them, but they’re figuring it out on their own and coming back to me in the classroom. That’s a paradigm shift,” he said.

During the week, small groups of students tried to determine whether a FCPA violation occurred by interviewing upperclass teaching fellows who played the parts of witnesses: the French company’s compliance officer and the area director for Africa.

Students started the area director interview by reading what’s known as the Upjohn Warning, letting her know that legal representation covered the company only, not her as an individual. They asked her about her background and questioned her relationships with the head of the charity and the timing and amounts of donations.

The lawyers learned that documentation was missing, the employee who approved large donations had mysteriously left the company, and a board member at the charity had specifically asked for donations, telling the area director, “Loyalty has its rewards.”

“What does that statement actually prove?” Cedrone asked the class later.

“It was interesting, and I tried poking at it, but alone, it doesn’t really prove much,” said Jordan Foley (L‘21). “I tried to go down a few rabbit holes like asking if they were childhood friends, and it didn’t work.”

In the simulation debriefing, Adam Silow (L ‘21) told Devlin Woods (L’20), the teaching fellow he interviewed, that he wasn’t sure how much to push her as a witness. “When I heard you say things like, ‘I don’t have the documentation,’ I was trying not to sound incredulous.”

Successful alumni offer counsel

On the fourth day of class, students presented their findings and recommendations to their client’s general counsel, played by practicing lawyers from Georgetown Law’s alumni network. Among them were four judges and the head of mergers and acquisitions for Skadden Arps, Ann Beth Stebbins (C’86, L’94), who sits on the Law Alumni Board.

In these client counseling sessions, students shared what they learned in their investigation and offered their conclusions on whether the payment was a FCPA violation. At times, alumni stepped in and guided the students.

Cedrone said the logistics of this course are challenging, but he never has to worry about motivating students. “I’ve got successful alumni coming in on Day 4,” he said, smiling. “They are the motivation.”