Bridging Language and Law at Georgetown

January 17, 2024

Stephen Horowitz (center) instructs students in Georgetown Law's Two-Year LL.M. Program with a Certificate in Legal English.

When lawyer and linguist Stephen Horowitz was teaching an online legal English course for Ukraine's Chernivtsi National University in fall 2022, he struggled to find appropriate topics to discuss with students living in a country at war.

The unexpected solution? Basketball. “The Ukrainian professor for the class was a big sports fan,” he said. “We began talking about the NBA at the beginning and end of each class. It was a welcome distraction and provided a much-needed connection to the outside world.”

Fostering that kind of cross-cultural connection is at the heart of Horowitz‘s work in the legal English field. As a professor at Georgetown Law, he runs the Georgetown Legal English Blog and instructs students in the Two-Year LL.M. Program with a Certificate in Legal English, the first program of its kind to pair a master of laws degree with an innovative legal English curriculum. This fall, some 40 new students began the program, which has enrolled nearly 500 students since it was founded in 2008.

Off-campus, Horowitz is involved in additional legal English projects designed for Ukrainian law students, Afghan judges in the U.S. and LL.M. students preparing for the bar exam.

We spoke with Horowitz about his work at Georgetown Law and beyond.

What is legal English, and how do you approach teaching it?

Legal English refers to working with students who don’t have English as a first language, like many LL.M. students and other foreign-trained attorneys, to help them get the most out of law school in the United States. For example, one of the biggest differences between legal writing in the U.S. and in most of the rest of the world is that the culture here is “writer-responsible,” meaning it is the writer’s job to make sure the reader understands. In other places, it’s the reader’s job to infer meaning. So I want my students to learn how to communicate effectively with their intended audience. We focus on questions like: What are the audience’s expectations for what you’re writing? What is the discourse style? And what language and grammar will accomplish the writing moves needed for the discourse style?

With our students, we like to reverse-engineer a lot of texts, including legal memos, exam-style essays and court opinions. For example, students might go through a law review article and try to notice the language differences between sentences with footnotes and those without. That kind of activity gives LL.M. students concrete experience in U.S. legal writing culture.

What sparked your interest in the field? What makes Georgetown Law’s approach unique?

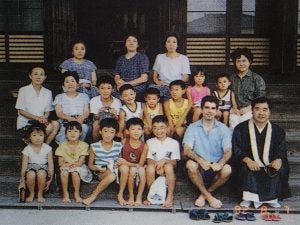

In the 1990s, Horowitz (bottom right) taught English abroad as part of the Japan Exchange Teaching (JET) Program.

I became interested in the relationship between legal studies and language after living and working in Japan, where I taught English for two years as part of the Japan Exchange Teaching (JET) Program. When I returned to the U.S., I went to law school and ended up working in bankruptcy law, but found myself missing cross-cultural interactions.

After hearing a friend describe her experience teaching English as a second language, I thought: That’s what I should be doing. I wanted to combine law and ESL and later learned that Georgetown Law was a pioneer in the field and the first U.S. law school to offer a legal English program.

At Georgetown Law, all of the two-year LL.M. classes are taught by a combination of lawyers and linguists. That is, half of the faculty have a Ph.D. in linguistics. The other half have J.D. degrees and legal practice experience. And several of us are lawyers who also have linguistics training or degrees in teaching English to speakers of other languages.

Professor Craig Hoffman, who directs the Georgetown Legal English program, has a wonderful approach to basing our work in the discourse of law. This is much bigger than simply teaching grammar or vocabulary – we want our students to understand how the word choices they make support their communication strategy and beyond that, tie into the discourse of law as it is practiced in the United States. When I was studying for my Masters in Teaching English as a Second Language, I read an article he’d written that completely changed my idea of what it meant to teach legal English.

What work are you doing with Ukrainian law students and professors?

As a result of the Russia-Ukraine war, as well as a new law pushing Ukrainian law faculty to start teaching their courses in English in the next year or two, there’s an increased need for legal training and English instruction in Ukraine.

I’m working with a peer-tutoring initiative with National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy in Ukraine. The program pairs Ukrainian students with those from Georgetown Law and other U.S. law schools, who served as mentors for a legal memo-writing project. I’ve also co-taught online legal English courses for Ukrainian law schools such as Chernivtsi National University and am part of an ongoing series of series of legal English training sessions for Ukrainian law faculty.

Like several of your Georgetown Law colleagues, you’re also a podcast host.

I co-host the USLawEssentials Law & Language Podcast with Dan Edelson, a professor at Seton Hall University School of Law and former colleague from St. John’s University School of Law.

Horowitz co-hosts the US Law Essentials Law & Language Podcast.

The podcast is aimed toward non-native English speaking law students and lawyers and is intended to provide listening and vocabulary practice. We pick an interesting legal news story – for example, Kim Kardashian trying to take the bar exam – and talk about it in an engaging, but slightly slower, way.

We also interview multilingual lawyers, an idea that was inspired in part by Professor Jonah Perlin‘s “How I Lawyer” podcast, and in part by Professor Hoffman, who instead of seeing international students as lacking English, encourages a view that values their multilingualism. LL.M. students may not be aware of the expansive range of law practice areas and law-related careers in the U.S. Among other things, our guests have worked at American law firms abroad, served as translators and practiced immigration and family law. My colleague Yi Song has also done a fantastic job in this vein with her “Master of Laws” series of interviews with lawyers from a range of international backgrounds.

What other legal English projects are on your roster?

Last semester, I helped design and carry out language assessments for a pilot program that provides funding for Afghan judges studying in the U.S. As part of that, Professor Edelson and I have developed an online legal English curriculum, some of which is based on the podcast.

For the past two summers, Professor Edelson and I have also offered an online bar exam essay skills writing course for LL.M. students, which is free for those in need.

What advice would you offer prospective LL.M. students?

Students often ask, “What should I read to prepare for law school?” The answer I generally give: Just read things in English that you enjoy. The cases you study in law school touch on so many different topics, from medicine to farming to transportation to fashion to technology and beyond. We also know that judges love to make cultural references in court opinions. So reading books and even watching movies and television in English is actually extremely helpful, both in terms of building cultural knowledge and improving reading speed.

Much of your work is focused on supporting students. What keeps you motivated?

Each spring, Horowitz (center) hosts a barbecue for students at his home.

I love connecting with others, especially cross-culturally. At the end of the fall semester, the legal English program has a potluck dinner where everybody brings some sort of food from their culture. Students take great pride in what they prepare, and everyone enjoys trying each other’s dishes. During the last potluck we had a raucous time playing an online language-guessing game called Language Squad. At the end of the spring semester, I also host a barbecue at my home for all of the students. That’s always a lot of fun.

Students from foreign language and cultural backgrounds often feel a tremendous amount of stress. When I lived in Japan, it was hard to adjust at first — but there were some people along the way who were kind and helpful in ways I could not have previously fathomed. So it’s always been important to me to try and pay that forward.