Clinic Students Win ‘Compassionate Release’ for Incarcerated Clients

April 13, 2021

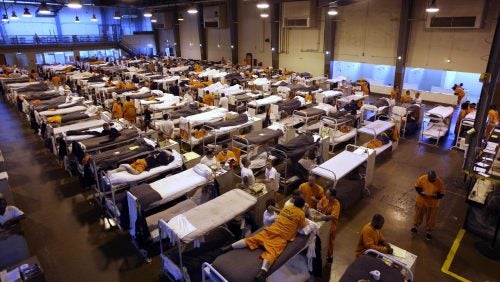

Several hundred inmates crowd the gymnasium at San Quentin prison in San Quentin, Calif.

When Nardos Bekele (L‘21) learned about the opportunity to seek “compassionate release” for incarcerated people with underlying health conditions during the pandemic, she jumped at the chance.

Nardos Bekele (L‘21)

“I am a Black woman, and I believe that it’s important that people within the criminal justice system are represented by people that look like them,” she said.

This fall, she enrolled in Georgetown Law’s Criminal Justice Clinic, a year-long experiential learning program in which students develop practical litigation skills like writing opening and closing arguments and negotiating with prosecutors. Bekele and her classmates were assigned “medically vulnerable” clients who were serving out sentences in crowded and unsanitary prison conditions, putting them at elevated risk of contracting and dying from COVID-19.

During the year, students and fellows interviewed clients, sought statements of support from family members, and drafted motions for their compassionate release — a federal program that allows inmates to be released early under certain “extraordinary and compelling” reasons, including serious health conditions.

After Bekele filed her motion, the government filed an opposing motion, which Bekele appealed. Ultimately, though, the judge sided with Bekele and her client. The verdict came on Dec. 23 — and Bekele’s client spent the holidays at home.

“It was the best gift ever,” Bekele said.

Bekele has since taken on another client, giving her a continued sense of purpose during an otherwise bleak time. “Giving someone a second chance has been the best part of my COVID experience,” she said.

Numerous Clients Released

All told, Bekele and her fellow students in the Criminal Justice and Criminal Defense & Prisoner Advocacy clinics have helped secure early release for more than a dozen clients this year.

Associate Professor Vida Johnson

“It ended up being the perfect type of work for the students who couldn’t go to court or meet clients face to face,” said Associate Professor Vida Johnson, who co-leads the clinics.

The work builds on a string of similar successes last year, when students in the clinics secured compassionate release for 15 clients serving out sentences for misdemeanors, such as theft and trespassing.

Typically, students in the two criminal clinics represent defendants charged with misdemeanors in the District of Columbia Superior Court and before the U.S. Parole Commission. But when area courtrooms shut their doors and suspended activities last spring, the clinics shifted focus. Johnson and Professors John Copacino and Abbe Smith — who co-lead the clinics — obtained a list of people serving sentences for misdemeanors, and students advocated on their behalf.

“The fellows really did an amazing job, cranking out motions and winning releases,” Johnson said. “The judges were also really good about understanding the risk.”

D.C. Emergency Measure Shifts Student Work

When the District of Columbia suspended misdemeanor prosecutions in late March, the clinics pivoted again. “There was this flurry in the spring, and then we thought, what can we still do?” Johnson said.

The answer lay in an emergency measure passed by the D.C. Council last April that made it possible for the first time for clinic students at area law schools to work on compassionate release cases for individuals convicted of felonies, such as burglary, rape, and murder.

Natalie Bayer (L’21)

Like Bekele, Natalie Bayer (L’21), a student in the Criminal Defense & Prisoner Advocacy Clinic, is seizing the opportunity to pursue justice from a distance. She currently represents two clients, one of whom is at a facility that went in full lockdown due to a severe spike in COVID-19 cases.

As a result, her client, who has been in prison for decades, has had fewer opportunities to exercise, contact his lawyers, see visitors, and access other legal and human rights. Not only is he at higher risk of death due to his illness, Bayer said, but his freedom is severely limited.

Bayer filed a motion seeking release for his conviction in D.C. Court, was granted a hearing, and convinced the judge to grant her motion to reduce her client’s D.C. sentence over opposition from the government.

“We were all just so happy,” said Bayer, adding that her client was thrilled that a judge finally “recognized the work he had put in” to rehabilitate himself in prison.

Bayer is now trying to secure her client’s early release in federal court while also advocating for another client in similar circumstances. Working in the clinic has confirmed her desire to pursue a career in public defense after she graduates this spring.

“I’m really excited to have had this experience before going into a job,” she said.

The silver lining, she added, is helping restore individuals to their families. “That’s not something that a traditional public defender in a misdemeanor clinic … gets to experience. It’s really motivating.”

“The Call of the Moment”

While the wins have been incredibly rewarding, they also come with some difficult realizations about the challenges of long prison sentences, Johnson said. She herself worked as a public defender before coming to Georgetown, and had little previous experience with people who had already spent years, even decades, incarcerated.

“Prison is terrible for your health in ways that I hadn’t really imagined,” she said. With limited access to fresh food and exercise, conditions like high blood pressure, diabetes, and obesity are rampant in the prison population. Regular check-ups are rare, and routine screenings like colonoscopies even rarer. “Guys in their 50s seem like guys in their 70s or 80s.”

Making matters much worse, prisons and jails are a “breeding ground for Covid-19,” Bekele added, noting that death rates from the virus are “significantly higher” among incarcerated people than in the general population.

While winning cases has been uplifting, losing them — knowing the dangers their clients face — has been devastating to the students and staff. “It feels like I went from teaching a misdemeanor clinic to a death penalty clinic,” said Johnson.

How, when, and whether these two clinics go back to “normal” operations is very much an open question, and depends on what misdemeanor prosecutions look like in D.C. after a year or longer with none. For now, they will continue to focus on the situation before them.

As Johnson put it, “This is the call of the moment.”