In New Book, Professor Brad Snyder Illuminates Overlooked History of Landmark Civil Liberties Case

April 10, 2025

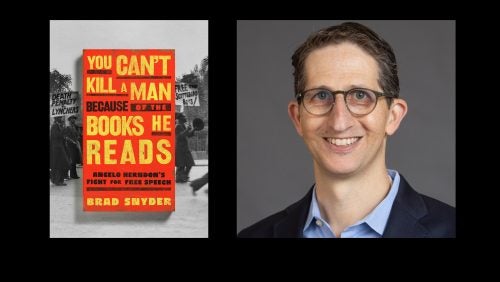

"You Can’t Kill a Man Because of the Books He Reads" (cover image left) is the newest book by Professor Brad Snyder.

Once among the most famous Black men in 1930s America, Angelo Herndon — a Communist Party organizer wrongly convicted of attempting to incite insurrection and sentenced to a chain gang by an all-white jury — has largely faded from public recollection in recent decades.

In You Can’t Kill a Man Because of the Books He Reads, Georgetown Law Professor Brad Snyder brings Herndon back into the spotlight, illuminating his years-long quest for freedom and the diverse coalition of lawyers who championed his cause — a legal journey ending with a landmark 1937 United States Supreme Court decision that freed him from prison and upheld the right to protest.

“Even though the protest that he led was peaceful, Herndon was a threat to the white political establishment,” Snyder says of the 1932 demonstration in Atlanta that Herndon, then 18 years old, organized on behalf of unemployed workers. He was then convicted under a slave insurrection statute at a time when such crimes were punishable by death. “That’s why he went on trial for his life.”

Below, Snyder discusses the ongoing relevance of Herndon’s case in light of free speech debates today, the role of courts in protecting civil liberties and how another Georgetown Law professor helped him unearth crucial archival details about Herndon’s life.

What inspired you to tell Angelo Herndon’s story?

After Black Lives Matter protesters were tear-gassed in front of the White House and the January 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol, I thought that the Herndon case was important and instructive when it came to understanding the difference between a constitutionally protected protest and one that devolves into incitement or violence.

In Herndon v. Lowry (1937), the Court established that if you’re going to abridge someone’s free speech rights and criminally charge them, there must be an imminent threat of physical violence. Herndon’s case is part of a vanguard of Supreme Court decisions that place limits on the states and their ability to punish people for political speech.

In light of the new presidential administration, free speech and the right to protest are top of mind for many. How can Herndon’s case help us understand these issues today?

I wrote this book before the change in political power in this country and as some of the newer free speech issues on college campuses were starting to emerge. I hope the book helps people understand that, together, the First Amendment rights to free speech and peaceable assembly create a right to protest that the Court established in Herndon’s case and others around that time. It’s only since these cases — in the last 100 years or so — that the courts have become the protectors of free speech rights and the right to peaceably assemble.

The book highlights the coalition of lawyers — including Black civil rights lawyer Benjamin J. Davis, Jr., leftist immigration lawyer Carol Weiss King and former Assistant Solicitor General Whitney North Seymour — who advocated on Herndon’s behalf. What lessons can we draw from their collaboration?

Lawyers from all across the country and all across the political spectrum freed Angelo Herndon. At the time, lawyers from the radical left and mainstream civil rights organizations were all working together to fight fascism at home and abroad. It’s important to remember that the rights to free speech and peaceable assembly are no accident: They were hard-won and fought for. Lawyers today need to remember that we can’t just sit back if we want to enforce our rights to free speech and assembly. That’s what we try to teach our students at Georgetown Law. Lawyers can make a difference in the world, just as they did in Herndon’s story.

The book also outlines Herndon’s life after the 1930s. Following the case, he rose to prominence as a Harlem literary star, but largely disappeared from the public record before his death in 1997. How did you research the later decades of his life?

Electronic newspaper databases were incredibly helpful, as were Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests. I also worked with Professor David Vladeck, who sued the National Archives in federal court so that I could have expedited access to a redacted version of Herndon’s FBI file. The FBI had been tracking Herndon from 1936 to about 1971, and their file was critical for me to be able to piece together Herndon’s life during that time. This is not the first time Professor Vladeck helped me recover FBI files. It was amazing that he was able to do that.

What are you working on next?

I’ve been working on a book about the Civil Rights Act of 1875, much of which the Supreme Court gutted eight years later with the Civil Rights Cases of 1883. In the majority opinion, Justice Joseph P. Bradley wrote that it was time for Black people to stop being the “special favorite of the laws.” My book, which is tentatively titled Special Favorite of the Laws, is about the story of the 1875 Civil Rights Act, how the Supreme Court overturned it and the damage that decision did to American law up until the 1990s.