Professor Cliff Sloan Explores ‘A Tale of Two Courts’ in New Book on FDR, the Supreme Court and World War II

November 14, 2023

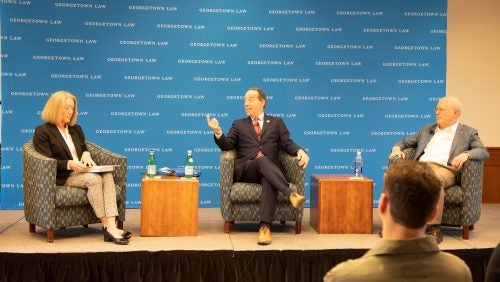

L-R: Prof. Mary McCord, Rep. Jamie Raskin and Prof. Cliff Sloan discuss Sloan's new book, "The Court at War"

By the summer of 1941, months before the United States entered World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt had appointed seven of the Supreme Court’s nine justices and handpicked an eighth for the role of chief justice. A new book by Professor Cliff Sloan is the first definitive account of the years following those appointments, which included landmark rulings on issues as varied as reproductive choice, voting rights and religious liberty.

By the summer of 1941, months before the United States entered World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt had appointed seven of the Supreme Court’s nine justices and handpicked an eighth for the role of chief justice. A new book by Professor Cliff Sloan is the first definitive account of the years following those appointments, which included landmark rulings on issues as varied as reproductive choice, voting rights and religious liberty.

“It was really a tale of two courts — the best of courts and the worst of courts — and they both very much related to the war,” said Sloan in a recent conversation about the book, “The Court At War: FDR, His Justices, and the World They Made,” delivered to an enthusiastic student audience at Georgetown Law.

Sloan was joined by U.S. Representative Jamie Raskin (D-Md.), ranking member of the House Committee on Oversight and Accountability and Professor Mary McCord, L’90, executive director of Georgetown Law’s Institute for Constitutional Advocacy and Protection, for a lively discussion about the Roosevelt court’s impact and legacy.

“When people usually talk about Roosevelt and the Supreme Court, they’re talking about the ‘court-packing’ plan,” Raskin said, referring to the president’s failed attempt to add as many as six justices to the bench. “But it’s very clear from the book that he was intensely interested in the work of the Supreme Court and appointed an all-star roster of justices who transformed the jurisprudence of the court and the court as an institution.”

A mixed legacy

As detailed in “The Court at War,” the Roosevelt court issued a series of decisions in which the court expanded constitutional rights, such as Skinner v. Oklahoma (1942), which struck down forced sterilization.

But cases like Korematsu v. United States (1944), which upheld the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II, highlight what Sloan called “the catastrophe that results when justices are unwilling to confront the president who appointed them.”

Many of the justices appointed by Roosevelt were “excessively close” to the president, Sloan explained – and thus were reluctant to oppose his wishes, particularly in war powers cases like Korematsu.

The trio also discussed how the shortcomings of the Roosevelt court illuminate contemporary debates over court ethics, such as the drawbacks of the presidential appointment process. For Sloan, the need for judicial guardrails is clear. “I think [the Roosevelt court] really illustrates the need for a strong ethics code,” he said.

Into the archives

Sloan, who teaches criminal justice, constitutional law and death penalty litigation as a Professor from Practice, said in a recent interview that he was inspired to write about the Roosevelt court while working as the Obama Administration’s special envoy for Guantanamo closure.

As part of that work, he read all of the Supreme Court decisions on military detention, including Hirabayashi v. United States, a 1943 case that upheld a curfew targeted at Japanese American citizens. One week before the Hirabayashi decision, Justice Robert Jackson had issued an opinion in West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette that upheld religious freedom for Jehovah’s Witnesses, another minority group.

“It struck me that within exactly seven days, the Supreme Court issued one of its greatest civil liberties decisions, and one of its worst civil liberties decisions,” Sloan said.

Sloan, right, with George Hutchinson, a source for his book.

To bring the court and its justices to life, Sloan researched at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library, the Library of Congress and National Archives. Georgetown Law librarians were invaluable in helping him locate relevant materials, he said.

Sloan also spoke with sources in person. George Hutchinson, now 100 years old, was an 18-year-old aide working at the Supreme Court library in that era. “He told me about seeing soldiers burst into the Supreme Court the morning after Pearl Harbor,” said Sloan — a detail that appears in the beginning of the book. The late Justice John Paul Stevens, for whom Sloan clerked in 1985, also shared with Sloan his own memories of the Roosevelt-appointed justices.

The court in context

At the end of his discussion with McCord and Raskin, Sloan thanked his student research assistants. One, Abby West, L’24, joined Sloan’s research team after taking his criminal justice class during her 1L year and spent time combing through the justices’ papers in the Library of Congress.

“It has been fun to see the book through the publication process,” West said, noting that thanks to Sloan’s encouragement, a Note about her research findings will be published in the Journal of Supreme Court History next year.

Kerry Walsh, L’21, now an associate at Arnold & Porter, said that as a transfer student, working as a research assistant helped her get engaged in the Georgetown Law community. She went on to take Sloan’s death penalty practicum during her 3L year.

“One of my favorite projects was digging through historical newspapers to find articles about the justices and their children, many of whom served in various capacities in the war. It was interesting to consider whether and how the justices’ personal feelings regarding the war could affect their rulings,” said Walsh, a self-described “history buff.”

Sloan agrees. “I think it is really important to bring the justices to life and to understand them as people and as and as people enmeshed in their times,” he said. “For all of the justices, the war was a very important context for their decisions.”

Watch the full conversation: