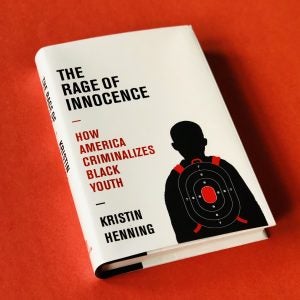

Professor Kristin Henning: Exposing What Black Children Endure

September 28, 2021

Professor Kristin Henning

In her new book, “The Rage of Innocence: How America Criminalizes Black Youth,” Blume Professor of Law Kristin Henning writes about her 26 years defending Black children prosecuted for offenses including “horseplay” on the Metro, throwing snowballs at a passing police car and playing catch with a teacher’s hat. She has seen children as young as 9 and 10 handcuffed, and counseled countless teenagers living with persistent anxiety that police will stop, search and interrogate them as they simply take a walk with friends or go for a bike ride.

“We live in a society that is uniquely afraid of Black children,” writes Henning, who served as a public defender in Washington, D.C., before joining the Georgetown Law faculty in 2001 to teach in, then lead, and then expand what is now called the Juvenile Justice Clinic and Initiative.

In her book, Henning takes a deep dive into adolescent psychology, the racially disparate responses to normal teenage behavior, and the trauma over-policing creates for Black youth. She also explores dehumanizing practices such as shackling; traces the roots of school-based policing to civil rights protests, not Columbine; and celebrates the resilience of Black youth captured in trends like #BlackGirlMagic and #BlackBoyJoy.

We recently spoke with her about the newly published book and her career as a passionate advocate for children, youth and racial justice.

What is your book about?

This book highlights the ways we as a society criminalize Black adolescence. The book brings research and data on bias and racial disparities to life by looking at some of the high-profile cases that people have heard about in the news and by drawing from my clients’ encounters with police. And, because I am convinced that most people are not aware of the extreme stress and anxiety that many children live with, the book also highlights the traumatic effects of policing on Black children.

Where does the title, The Rage of Innocence, come from?

It’s about the rage we should all have when we deprive any child of the freedom to be children.

It’s about the rage we should all have when we deprive any child of the freedom to be children.

We can all remember what our teen years were like. We were impulsive, reactive, and enjoyed our friends. We challenged authority and tested limits, but ultimately, we were resilient and creative. We should afford every child that opportunity. Those years of growth, experimentation, and joy and laughter make us better and more successful adults. We do ourselves a disservice — and we certainly do Black youth a disservice — when we fail to treat all children like children. We should all be enraged about that.

But there are some nuances to the title as well. The rage of innocence is also what happens when children – especially Black children — are excluded from Western notions of childhood innocence. It’s what happens when we repeatedly tell Black children that they are bad and dangerous and criminal. Black youth resist those labels. And they begin to resent those who force those labels upon them. The tension between Black youth and the police is at an all-time high, owing in part to this dynamic. Officers — and civilians — presume that Black youth are dangerous and to be feared and treat them that way. Black youth then push back the best way they can – sometimes verbally, sometimes physically, and sometimes by avoidance.

Your first professional experience with the law was actually behind a prosecutor’s desk when you were in college. How did that set you on your path?

I had an apprenticeship in the district attorney’s office in North Carolina. I will never forget walking into the courthouse and seeing a line of teenagers chained together. I stopped in my tracks.I sat down next to the DA and I said to her, “Honestly, I really want to be over there,” and I pointed to the defense counsel table with the young people. So that was my a-ha moment. And then when I decided to go to law school, I only applied to schools that had a clinical offering in youth justice.

How did the U.S. approach to juvenile justice develop over time?

The first juvenile court started in 1899 with a “child-saver” mentality, or rehabilitative approach, but by the time we hit the 1950s and 60s, with the civil rights era, and then certainly by the time we hit the 80s and the 90s, with the crack epidemic and the rise of the victims rights movement, we really lost touch with the rehabilitative ideal of juvenile court and shifted to a law and order focus. Recent efforts in youth justice reform arise out of the need to get us back to that rehabilitative ideal, to remind us that children are different from adults, that the philosophy of deterrence that is commonly attached to criminal courts doesn’t make sense for children, who rarely think ahead to the consequences of their actions.

You now lead racial justice trainings around the country for juvenile defenders, prosecutors, judges. Did you go into this work seeing it through a racial justice lens, or did that develop along the way?

To be honest, it developed along the way. It is impossible, as a Black woman raised in the south, to not know there’s racial discrimination. But when you dig deep on any one topic, whether it’s housing, education, or, in my case, the juvenile legal system, it really slaps you in the face. In Washington, D.C., in 26 years of practice I have literally had only four white clients — in a city that is not 99% Black, by any stretch of the imagination — it just blows your mind.

I was once at a conference and I was speaking about a client who was charged with possession of a Molotov cocktail for bringing a glass bottle with liquid and toilet paper sticking out the top to school. It wasn’t flammable, it was just a toy, and he got charged and expelled. A white woman said to me afterward, “My son did the same thing. They put him in advanced science class, because he was so curious.” Black kids are treated differently, and it’s appalling.

Your scholarship on “The Reasonable Black Child” has been cited in several amicus filings, as well as by the Juvenile Law Center in awarding you its prestigious Juvenile Leadership Prize. How did you get the idea?

In juvenile court, police officers often say, “That kid was suspicious because he took off running when he saw me.” And I’m thinking, “No — he took off running because he was terrified of you!” Judges largely interpret a child’s flight or nervousness as evidence of consciousness of guilt under the Fourth Amendment. The courts — even the Supreme Court — are just wrong about this. There is psychological research showing that many adults are anxious around police for all kinds of reasons, and then add adolescence to that, and then layer race on top of that. A reasonable Black child is afraid of the police. Judges are increasingly more amenable to what it means to be a Black adult and a Black child, so I’m excited about the momentum of that article.

What do you hope people will learn from reading your book?

I want people to understand just how pervasive the criminalization of Black youth is and to commit to change. A handful of people who read advanced copies of the book — folks who are active in the criminal legal space — didn’t realize just how bad it was for kids, in particular. I think what’s fascinating is how complicit we all are in the disparate treatment of adolescence, largely because it is so deeply ingrained in our psyche. Everybody keeps talking about implicit racial bias. It’s real, the cognitive sciences are real. We all have to do our part in altering the harmful narratives about Black children and learning to treat them as children.

In 2024, the Georgetown Law Juvenile Justice Clinic celebrated its 50th anniversary. Read more about its founding and its evolution over the decades.