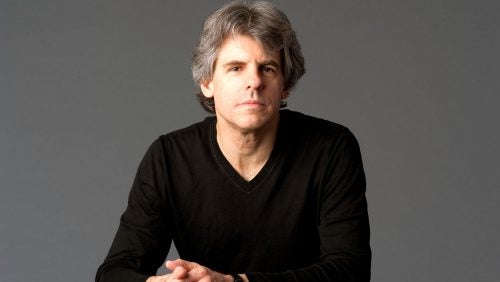

Professor M. Gregg Bloche on New Revelations about U.S. Torture Programs and the Ethics of Interrogation

March 17, 2020

Professor M. Gregg Bloche

On March 5, top experts on torture and interrogation programs came together at Georgetown Law to discuss new revelations about U.S. actions after 9/11. In remarks, followed by a panel discussion, organized by Georgetown Law Professor M. Gregg Bloche, speakers analyzed efforts to ensure ethical approaches to securing critical national security information. Bloche — who is author of The Hippocratic Myth and contributor to a new book, Interrogation & Torture — holds both a J.D. and M.D. and teaches health law and policy and the course “The Mind and the Law.” We asked him what’s new and what should happen next.

Q: Can you detail the new revelations on torture that recently came to light?

Bloche: January hearings at Guantanamo Bay yielded new clues about the United States’ approach to waterboarding and other harsh interrogation methods after 9/11. CIA psychologist James Mitchell provided new details about the “enhanced interrogation program” that he designed, and he suggested the agency used other programs that may have been even more brutal.

Other information that has recently come to light includes new detail about the role of physicians, as well as how U.S. officials subverted medical and psychological ethics.

Q: What are some of the questions that you are asking after these hearings?

Bloche: We don’t know whether the CIA had an ongoing, previously unrevealed capacity to conduct this kind of interrogation. Was the separate, more brutal program the product of post-9/11 thinking, or had the CIA secretly retained this capability for decades after the 1970s and early 1980s, when we thought the Agency had shut it down? Did a few CIA agents or officials go rogue after 9/11, or was there a still-unrevealed program of brutality by official design?

Q: Why is the role of doctors in designing torture techniques within the CIA significant?

Bloche: We have learned recently more details about the deeply-embedded role of physicians in designing waterboarding techniques. They also engineered the details of brain-endangering sleep deprivation, agonizing stress positions, and throwing people against walls. The hearings showed that the physicians made suggestions about use of saline in waterboarding, monitored interrogators’ waterboarding “pours,” and otherwise managed the intensity and sequencing of these abuses.

Q: What kind of legal and ethical questions should students watching these hearings at Guantanamo ask?

Bloche: How could Mitchell, as a psychologist, be involved in this given his professional ethics, which are similar to healthcare ethics? Mitchell said he was acting as an interrogator, not as a psychologist, and therefore psychological ethics were irrelevant. CIA officials said, internally, that Mitchell and the participating physicians acted ethically because they served the greater good – and that psychology’s and medicine’s professional ethics didn’t matter.

It is important to see this as a breakdown of governance at multiple levels. The process of defining and enforcing ethics within the CIA failed. The psychological ethics process within the profession failed. Lawyers gave their government clients what they wanted rather than making judgments rooted in law about what was permissible. They failed to follow their ethical obligations to give the best, well-grounded advice, and our national leadership joined in this frenzy of disregard for governing ethical and legal norms when it came to torture.

All of us, whatever we do within or outside the legal profession, may be asked to work in a way that violates our ethical obligations. We are all susceptible to groupthink that makes it hard to be skeptical about what we are being asked to do. Even as we try to be good ethical citizens, we should maintain a professional stance of constant questioning. That will empower us to have a sense of self and a sense of duty when it comes to being asked to do things at odds with ethics and the law.

Q: What are some of the efforts by governments to make sure this kind of thing doesn’t happen again?

Bloche: One endeavor that was underscored at the Georgetown Law event was the draft international protocol on noncoercive interrogation. The goal of this protocol is to create international norms for professionals who seek to extract information from detainees for national security purposes. This guidance can encourage interrogators to use science-based methods grounded in state-of-the-art of cognitive psychology and the behavioral sciences. The challenge here is to make sure those charged with protecting our nation’s security conduct themselves within the constraints of their own professional ethics.

Q: What are some alternative techniques that can be used other than torture to obtain information?

Bloche: Cognitive psychology can be tapped to help interviewers to access people’s memories. There are ways to enable people to recall things they may not initially recall, either through verbal cues or experiences and sensations that evoke people’s pasts. A smell, a feeling or a song can evoke a memory. I’m not saying interrogators should sing to detainees or serve them tea, but the larger point is that there are ways to evoke memories and experience that don’t involve torture.

There is also rapport building. That doesn’t mean being warm and fuzzy all the time. But it means building relationships that can reorder a person’s sense of what he or she should and shouldn’t say.

Q: What were some of the other key takeaways from the presentations last week?

Bloche: I ask the question — what were they thinking? The folks who designed and engineered the techniques — what were they thinking in terms of anger at those who did country harm? Perhaps panic followed the attacks. What broke down by way of the guardrails that constrain our behavior? It is worth asking the question after the fact — how did this happen and what were they thinking? It is not a rhetorical question.

One of our speakers, Susan Brandon (former research director with the interagency High-Value Detainee Interrogation Group), spoke quite hauntingly at the end of her prepared remarks, saying she would expect governments to go ahead with torture in the future based on the intensity of the public’s reaction to a hypothetical future mass terror event. Maybe she is right. But if there is a high-profile effort to develop effective norms, maybe there will be a greater desire to do things differently. There needs to be a plan on the shelf that incorporates the norms against excess and make it clear that these norms are vital.

Watch the full event, “America’s Misadventure in Torture: New Revelations and Hard Questions,” here:

Speakers include Daniel J. Jones, the lead author of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence’s Report on the CIA’s Detention & Interrogation; Juan Mendez, the former U.N. special rapporteur on rorture and professor of human rights in residence at American University; Georgetown Law Professor David Luban, author of Torture, Power & Law, and contributor to Interrogation & Torture; Alka Pradhan, human rights counsel for the Guantanamo Military Commissions; Mark Fallon, former Military Commission chief investigator and co-editor, Interrogation & Torture, author of Unjustifiable Means and director of ClubFed LLC; Susan E. Brandon, former research director, High-Value Detainee Interrogation; and Steven Barela, lead editor, Interrogation & Torture, and senior research fellow, University of Geneva.