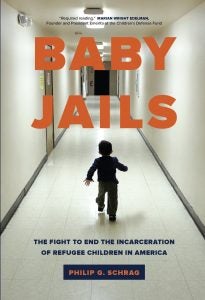

In a New Book “Baby Jails,” Georgetown Law’s Philip Schrag Charts U.S. Detention of Child Refugees Over Time

January 21, 2020

Professor Philip Schrag

Philip Schrag, the Delaney Family Professor of Public Interest Law, has authored or co-authored more than a dozen books. His latest, “Baby Jails: The Fight to End the Incarceration of Refugee Children in America” (University of California Press) publishes on Jan. 21.

We sat down with Schrag, who co-directs Georgetown Law’s Center for Applied Legal Studies asylum clinic to discuss the detention of children seeking refuge in the United States.

Your book charts the history of the Flores Settlement Agreement. What makes the Flores Agreement significant? What recent events have renewed its importance?

In 1985, 15-year old Jennie Flores fled from the civil war in El Salvador to seek safety in the United States. When she arrived, the U.S. government put her in a makeshift jail. She would have remained there for a long time, awaiting a hearing that could have resulted in her deportation, but another girl who was jailed with her was the daughter of the housekeeper of the actor Ed Asner. Asner obtained a lawyer for the girls, and they became plaintiffs in a class action that the government settled in 1997. The Bush, Obama and Trump administrations all sought to jail asylum-seeking families with children for long periods of time, but a 2015 court order enforcing the Flores Settlement has prevented ICE from keeping the families locked up for more than 20 days.

Family detention and family separation have been repeatedly used as a deterrent to immigration. What legal and practical reasons argue against this practice?

A fundamental principle of American law is that, except in the case of criminal offenses, the government can’t lock some people up to deter undesirable behavior by other people. But that is exactly what the government is doing when it incarcerates migrant children to discourage other families or children from seeking safety in America.

The Trump administration failed in its attempt to deter people from coming to the United States to escape from extortion and murder by gangs and from violent husbands and boyfriends in Central America. It then resorted to even more drastic and legally dubious means, such as issuing a regulation that purports to bar asylum for people coming over the Mexican border who did not first seek asylum in Mexico or some other country through which they passed. That regulation is now being challenged in the courts.

The Trump administration failed in its attempt to deter people from coming to the United States to escape from extortion and murder by gangs and from violent husbands and boyfriends in Central America. It then resorted to even more drastic and legally dubious means, such as issuing a regulation that purports to bar asylum for people coming over the Mexican border who did not first seek asylum in Mexico or some other country through which they passed. That regulation is now being challenged in the courts.

What are the greatest threats currently faced by refugee children and families?

Right now, the greatest threat is that the United States is exposing them to violent assaults and kidnappings in Mexico and Central America. Instead of providing due process in immigration courts as the immigration law requires, the Trump administration is excluding them without consideration of their claims. More than 55,000 asylum-seekers, including families, have been forced over the Mexican border to await hearings in the United States. In Mexico, they have no lawyers to help them obtain evidence for their cases, and they have been preyed on by criminals who have kidnapped many of them for ransom. In addition, the United States is dumping Honduran refugees, including families, in Guatemala, which lacks a functioning asylum system.

How have your personal experiences with asylum seekers and detained children contributed to your understanding of the issue of the detention of immigrant families?

For the last 25 years at Georgetown Law, I have directed an asylum clinic in which law students, under supervision, represent adults and families who seek asylum but are being threatened with deportation. The students present evidence to show that these refugees reasonably fear persecution in their home countries, and the students argue for them before federal immigration judges. Supervising these cases has made me realize how brutal some governments are toward political dissidents or religious minorities, and how arbitrary our own asylum adjudication system is when deciding the claims of people who have had to flee.

In addition, I volunteered for a few days at the family jail in Dilley, Texas. I was horrified by seeing toddlers in this prison-like setting, bewildered by being confined with their mothers and ordered about by employees of our private prison complex. This experience inspired me to write Baby Jails.

What can law students and practicing lawyers do to make an impact in improving the condition of refugee children?

Lawyers and law students can volunteer with organizations at the Mexican border to help arriving families deal with processing by the border authorities. They can also volunteer in the family detention centers to help parents pass their screening interviews so that they have a chance to see an immigration judge. Lawyers, as well as law students in clinical programs such as mine, can represent adults, families, and children in interviews with Homeland Security asylum officers and in deportation cases in immigration courts.

[Georgetown Law’s Detained Families Seeking Asylum Project has recently organized several one-week trips for student volunteers to assist detained families in Dilley and Karnes, Texas. Another group of 15 students, fellows and faculty will travel to the Dilley jail this coming Spring break.]

You identify political, economic, environmental and other factors resulting in surges in immigration. What areas provide the best opportunity to effect positive change?

The United States should be providing substantial foreign aid to Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala to help their governments quell the violent gangs and to eliminate corruption in the police force, such as officers who cooperate with the gangs and ignore complaints from their victims. Unfortunately, the Trump administration first cut aid to those countries. It then restored some of the aid after those countries agreed to let ICE “transfer” refugees to them. So we are now putting asylum-seekers on planes that take them to dangerous Central American nations other than their own.

On March 16 at 4:30 p.m., Georgetown Law will host a book event for Baby Jails with Schrag, fellow Georgetown Law professors Daniel Ernst and David Cole (currently on leave to serve as ACLU legal director), and Karen Musalo, director of the Center for Gender and Refugee Studies.