Professor Carlos M. Vázquez Installed as Scott K. Ginsburg Professor of Law

September 25, 2019

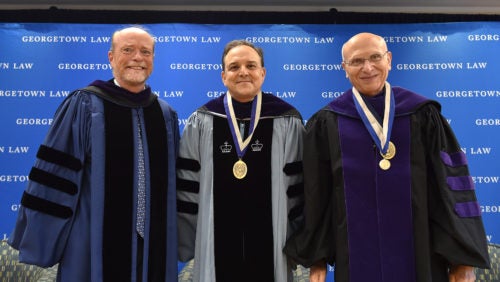

Dean William M. Treanor, Professor Carlos M. Vázquez, and Professor David Luban at Vázquez's installation as the second Scott K. Ginsburg Professor of Law on September 25.

“Human rights law has transformed international law not just in content but also in form,” said Professor Carlos Vazquez, who was installed as Georgetown Law’s second Scott K. Ginsburg Professor of Law on September 18.

While celebrating the growth of human rights as a subject of international law, Vázquez expressed some concern that the “softer” enforcement mechanisms characteristic of some human rights norms may be creating the mistaken impression that human rights law – and international law more broadly – is in general soft and optional.

In an address titled “Human Rights and the Transformation of International Law,” Vázquez raised the concern “from the perspective of someone who sets great store in international law generally as well as human rights [law] in particular — I’ve personally benefited in profound ways from both.”

Vázquez, who moved to the United States from Cuba at the age of 4 with his 24-year-old mother and three younger brothers, told the audience — which included his mother and other relatives — that his whole family received refugee protection in the United States. His father had supported the revolution in Cuba but lost faith when the country turned to Soviet-style communism. For many months before Vázquez’s father moved to the U.S., he benefitted from diplomatic immunity in the Brazilian embassy in Havana, which provided asylum and allowed him to escape arrest and possible torture.

Professor Carlos Vazquez is installed as the second Scott K. Ginsburg Professor of Law.

Vázquez, who has written and taught primarily in the areas of international law, constitutional law, and federal courts, was the founding director of Georgetown Law’s Human Rights Institute. He previously served as a law clerk to the Honorable Stephen Reinhardt of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit and practiced law with Covington and Burling in Washington, D.C. Vázquez joined the law school faculty as a visiting professor in 1990 and as an associate professor in 1991. He served as a member of the Organization of American States’ Inter-American Juridical Committee and was nominated by President Obama to the United Nations Committee for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, on which he served from 2012 to 2016.

Pathbreaking

In his welcome remarks at the installation, Dean William M. Treanor said he recognized Vázquez as a superstar in the making when they first met as freshmen at Yale.

“I remember just being dazzled by Carlos, that he was such a remarkable combination of someone who was brilliant but also so concerned about other people — and so humble,” Treanor said. “What we’ve seen over the years is the way in which that early promise has been so powerfully fulfilled. He’s a brilliant, pathbreaking scholar, he’s a committed and caring teacher. He’s somebody who is focused not just on the world of academia but on the world as a whole.”

Professor Carlos Vazquez and Professor David Luban.

Professor David Luban, who introduced Vázquez, noted that the latter was among the first to argue that the Guantanamo military commissions were unconstitutional, that he tackles some of the most technical and complicated areas of international and constitutional law, and that he knows these areas “the way that chess grand masters know the Queen’s Gambit.”

“There are a lot of legal grand masters on this faculty,” Luban added. “But what sets Carlos apart is how much he loves a deep dive into the law at a moment’s notice, always done with gusto and irony and with a happy twinkle in his eye.”

In his address, Vázquez said the most profound way that the emergence of human rights changed international law is by recognizing for the first time that the way a nation treats its own people is a proper subject of international scrutiny. He said that, unfortunately, some courts in the United States have painted with a broad brush and treated broad categories of international law as irrelevant to their work. “For example, the Convention for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination rather clearly prohibits states from discriminating on the basis of national origin,” he said, “yet international law was largely absent from the debate and litigation over the travel ban.”

He has urged domestic judges to be more attentive to the distinction between hard and soft law in international law, and he proposes taking more care in distinguishing “what human rights requires as a matter of binding international law on the one hand and the advancement of human rights as a moral imperative on the other hand.”

Welcoming

Scott K. Ginsburg (L’78) and Professor Carlos Vazquez.

In recounting the story of his family fleeing Cuba, Vázquez said the experience was harrowing — but arriving in America was not. “That was a time when [the United States] welcomed persons fleeing persecution,” he said. “I fervently hope that becomes true again.”

The Ginsburg Professorships were made possible through the generosity of Scott K. Ginsburg (L’78), who was present at the event. Ginsburg’s recent $10.5 million gift, the largest single gift in Georgetown Law history, will allow the school to expand its Washington, D.C., campus and will also support talented faculty members. Two other Ginsburg professors will be honored later in 2019; Professor Rosa Brooks was honored earlier this year.

“Scott’s is a name that we all know,” Treanor has said, noting that Ginsburg’s generosity has allowed the Law Center to build, design or acquire its iconic clock tower, the Ginsburg Sport and Fitness Center, the building next door, and these professorships. “Scott was dedicated to making this truly a campus…we are [a] community, principally because of [him].”