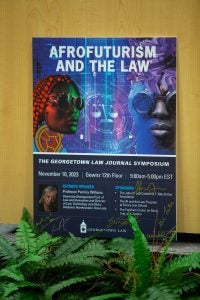

The Georgetown Law Journal Hosts 2023 Symposium on ‘Afrofuturism and the Law’

November 20, 2023

Interdisciplinary legal scholar Patricia Williams of Northeastern University School of Law delivered the symposium's keynote address.

Popularized by the "Black Panther" film series and the work of science-fiction authors such as N. K. Jemisin and Octavia Butler, the Afrofuturism movement — which merges futuristic themes with Black aesthetics and culture — is largely known as an artistic genre.

Symposium speakers autographed the event poster as a keepsake.

But a growing number of legal scholars are using Afrofuturism as a framework to examine racial injustice and the law. Their work was in the spotlight at The Georgetown Law Journal’s Nov. 10 symposium on “Afrofuturism and the Law,” the Journal’s first in-person symposium since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

This year’s symposium — the first on this theme in the United States — brought together professors from Georgetown University Law Center and interdisciplinary scholars from across the country. Professor Bennett Capers of Fordham Law School, whose proposal for the symposium was one of many the Journal considered, was joined by Professor Ifeoma Ajunwa of Emory University School of Law and Professor Etienne Toussaint of the University of South Carolina’s Joseph F. Rice School of Law in working closely with the Journal to plan the event, which was co-sponsored by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the AI and the Law Program at Emory Law School and Fordham’s Center on Race, Law and Justice.

“Afrofuturism has been building as an area of legal scholarship,” said Alexis Marvel, L’24, current editor-in-chief of the Journal. “It’s a way to both reckon with our history and chart new paths in the law using a theoretical lens traditionally outside the realm of legal doctrine.” Symposium participants discussed how such an outlook leads to a greater awareness of systemic racial injustice in law and can drive the dissolution of racist laws and legal principles.

Imagining a better world

During the panel “Imagining an Afrofuturist World” moderated by Professor Jamillah Bowman Williams, Capers and other speakers offered their vision of what a so-called “Afrofuture” looks like, including the role of lawyers in shaping it.

“One of the central tenets [of Afrofuturism] is that Black people and people of color exist in the future,” Capers said. “The first job of an Afrofuturist legal scholar should be to remember that much of Afrofuturism is about imagining different, better worlds.”

“Too often with legal scholarship, the focus is on marginal change in the present,” he noted, urging the audience to imagine the legal landscape as a “tabula rasa” in which new laws — even a new constitution — are possible.

Ajunwa also advocated for a proactive approach. “Afrofuturist lawyers should not complacently uphold laws that are deeply rooted in racism,” she said. “They should call out laws or legal processes that they see are actively enacting racism.”

Those ideas were echoed by Professor Michele Goodwin, co-faculty director of the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law and moderator of the panel “Race, Technology, and Legal Imagination.”

“Today’s presentations have challenged us to think of an Afrofuturism that is not confined to a spectacle of Black pain, but that is liberatory, democratic and hopeful,” she said.

Georgetown Law Professor Michele Goodwin, left, moderated a symposium panel that also included Professors Ifeoma Ajunwa (Emory Law) and Jessica Eaglin (Cornell Law) and Cierra Robson (Ida B. Wells JUST Data Lab at Princeton University).

Race, technology and the law

Many speakers highlighted the relationship between race, technology and the law. In her keynote address, pioneering legal scholar Patricia Williams, professor of law and humanities at Northeastern University, explored the interplay of identity and privacy in a world increasingly shaped by — and dependent on — computer code and algorithms.

“The designers of computer software can mislabel [genetic data] with words that carry ethnic, racial, religious, class, national or other status baggage,” said Williams, whose current research focuses on how racial categories are shaped by the legal regulation of private industry and the government. Technology, she explained, can leave users vulnerable to privacy violations with no legal protection.

Despite the potential for abuse, Capers expressed an optimistic technological outlook. “Afrofuturism has an interesting relationship to technology,” he said. “Rather than people of color simply being passive recipients of technology or victims of technology, they’re also the creators and purveyors of technology” — and, he noted, can use technology to work toward equality.

Afrofuturism in practice

For Executive Symposium Editor Margaret McCallister, L’24, the event offered an opportunity to explore Afrofuturism across disciplines. To prepare for the symposium, members of the Journal visited “Afrofuturism: A History of Black Futures,” an exhibition at the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

For the symposium lunch, she turned to Bronze, a local Afrofuturist restaurant whose globally-accented African and Caribbean menu offerings are inspired by the imagined world travels of a 14th-century African character called Alonzo Bronze, named after the owner’s great-grandfather.

“A lot of the day was spent talking about the theory of Afrofuturism, which is abstract,” said McCallister, but the meal was a “physical, tangible” reminder of how Afrofuturism can be put into practice.

Volume 112, Issue 6 of The Georgetown Law Journal is scheduled for publication next summer in print and online. It will feature ten essays by symposium speakers and two student notes.

“We’re really grateful and pleased with how it turned out,” Marvel said of the event. “We have a lot to do between now and publication of the symposium issue, but this event has absolutely reinvigorated us for the work ahead.”

The 2023-24 staff of The Georgetown Law Journal