The Future of NAFTA and North American Economic Integration Conference

On Friday, October 6, 2017, the Center for the Advancement of the Rule of Law in the Americas (CAROLA) at Georgetown Law hosted the conference “The Future of NAFTA and North American Economic Integration” to examine the legacy of NAFTA, the ongoing negotiations, and the agreement’s potential futures. The conference took place just a few days before NAFTA’s fourth round of negotiations was held in Washington, D.C.

This one-day conference was co-sponsored by Georgetown University’s Center for Latin American Studies (CLAS), Latin America Leadership Program, and Latin America Initiative. It convened government officials, scholars, policy analysts, members of civil society, and nongovernmental organizations as speakers (a total of thirteen), and included three panels:

Karen Antebi, the Economic Counselor for the Trade and NAFTA Office of the Embassy of Mexico in Washington, D.C. delivered the lunch keynote address.

View the full conference program.

Summary of Discussions

Professor Alvaro Santos, Faculty Director of CAROLA, remarked during his welcoming address that the conference focused on NAFTA not only because of the agreement’s importance to the parties involved and to the North American region, but also because NAFTA may serve as a litmus test for how the challenges to international trade in the U.S. will be channeled. To quote Professor Santos: “where NAFTA goes, so does trade.”

Professor Santos reminded the audience that NAFTA had come under attack by the current U.S. administration, which had called for the agreement’s renegotiation and even withdrawal. In its critiques of trade and NAFTA, the Trump administration has fueled a sentiment of economic nationalism, often accompanied by racial and xenophobic rhetoric. But, in forcing the parties to renegotiate the agreement, the U.S. has also created an opportunity to reevaluate its legacy and discuss an alternative model. “Can we use this opportunity to reimagine the treaty in the service of a more prosperous region and therefore a more prosperous United States, a more prosperous Mexico, and a more prosperous Canada? What would that NAFTA look like? Can we use the current crisis as an opening to experiment and take seriously the backlash and the discontent that has fanned the political opposition to trade?”

Professor Santos reminded the audience that NAFTA had come under attack by the current U.S. administration, which had called for the agreement’s renegotiation and even withdrawal. In its critiques of trade and NAFTA, the Trump administration has fueled a sentiment of economic nationalism, often accompanied by racial and xenophobic rhetoric. But, in forcing the parties to renegotiate the agreement, the U.S. has also created an opportunity to reevaluate its legacy and discuss an alternative model. “Can we use this opportunity to reimagine the treaty in the service of a more prosperous region and therefore a more prosperous United States, a more prosperous Mexico, and a more prosperous Canada? What would that NAFTA look like? Can we use the current crisis as an opening to experiment and take seriously the backlash and the discontent that has fanned the political opposition to trade?”

After quoting John Kenneth Galbraith’s 1958 book “The Affluent Society,” Professor Santos challenged the guests and panelists to use the political events of the past two years to revisit the “conventional wisdom” in the international trade debate. He urged that we ask ourselves if we have been operating solely in the realm of the familiar, and consider if we would be willing to venture to new and uncharted territory, even if these ideas were not met with approval.

The conference was designed with that challenge in mind. The first panel was set up to provide a diagnosis of the effects of NAFTA in each of the countries involved, and to assess if the agreement accomplished what it set out to do. Who won and who lost from the treaty in each country? What were the agreement’s institutional innovations and its dysfunctions? Should we promote its continuation? The conversation of the first panel built into the second panel, which examined the priorities of each country in the negotiations and what they should be pushing for. What are the areas of consensus and of friction? What would a NAFTA that incorporates the lessons of the past 23 years look like? Has NAFTA struck the right balance between capital and labor?

The second panel was followed by lunch and a keynote given by Karen Antebi, in her capacity of economic counselor for NAFTA and trade at the Mexican Embassy in Washington, D.C. Her presentation provided a survey of the reasons why her government considers NAFTA to have been positive for Mexico and for the region. While it is common to hear the position of the U.S. government, especially in the nation’s capital, we wanted to hear the position of its Mexican counterpart.

Finally, the last panel considered NAFTA along with its repercussions and reactions at the national level. If theory predicts losers from trade, what have countries been doing to compensate them and to distribute the accrued gains in a way that makes trade legitimate? If NAFTA has turned out not to be a development strategy on its own (a question that is particularly important for Mexico), what national policies can countries undertake to promote growth in a way compliments the agreement?

Please find a brief summary of our panel discussions regarding these and other NAFTA-related questions below.

Panel 1 – The Balance of NAFTA

Duncan Wood, Director of the Mexican Institute at the Wilson Center and chair of the first panel, kicked-off the discussion with an analogy, comparing the relationship between Canada, Mexico, and the U.S. to a long-term sentimental relationship in which one of the partners is unhappy and ultimately wants to break it up. “We’ve been in this relationship for a couple of decades and we’ve been getting on fine, what is it you don’t like about me now?” quipped Mr. Wood. “It is not you, it is me. I’ve changed” the partner would say. Mr. Wood announced that the panel was going to have a frank discussion about winners and losers and whether NAFTA could undergo a relationship change.

The panel’s first participant was Rufus Yerxa, President of the National Foreign Trade Council, who shared insights about his experience putting together the final deal that became NAFTA. He expressed his dissatisfaction with how the debate of NAFTA had ultimately turned into a discussion of “jobs” and “increases in trade” rather than “industrial performance” or “efficiency,” while acknowledging that there was a gap between the promises of NAFTA and what it actually delivered. According to Mr. Yerxa, NAFTA delivered a much stronger North American economic platform, more robust economic performance, and the ability to compete. There have been so many fundamental changes that resulted from the agreement, that the question to ask is not who gained more, but how much damage will come from a withdrawal from NAFTA.

Laura Dawson, Director of the Canada Institute at the Wilson Center, spoke next. She argued that “trade is in Canadian DNA.” Trade with the U.S. has been a defining part of Canadian history with the U.S. since around 1776. However, it was only until 1888 that Canada took the “leap of faith” into open trade by signing an agreement with the U.S. Today, Canada and the U.S. are each other’s largest trading partners, but 20% of Canadian GDP comes from that trade, whereas only 2% of U.S. GDP comes from trade with Canada. That big disparity has been incredibly challenging for Canadians. Ms. Dawson also posited that NAFTA negotiations have dissolved into two different negotiations: one about “modernizing” the agreement and another about “turning the clock backwards.” Given that the U.S. seems intent on tabling regressive proposals, some Canadians are now feeling that they are, to borrow Ms. Dawson’s words, “going to have to walk away from the negotiations.”

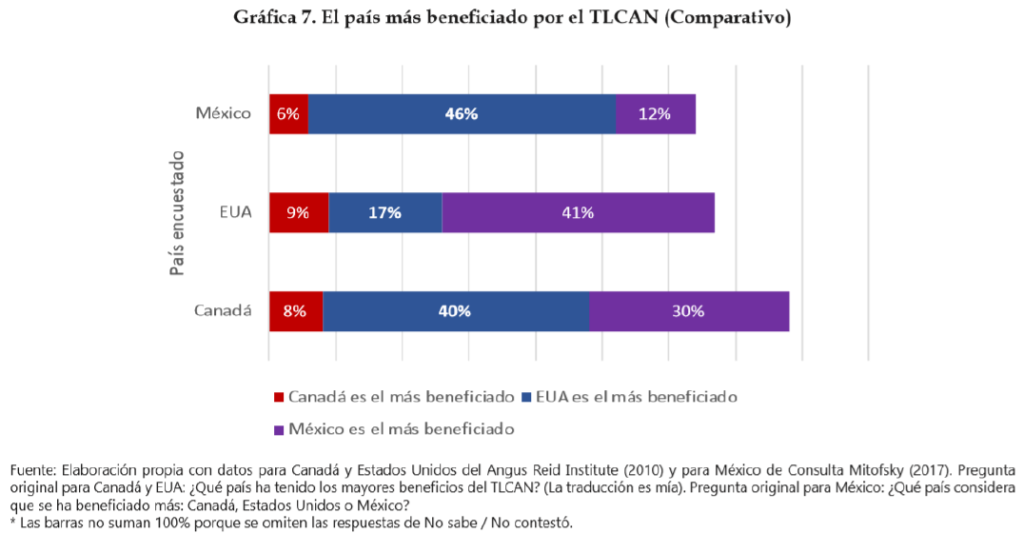

Afterwards, Gerardo Esquivel, Professor at El Colegio de Mexico shared an insightful survey of perceptions about NAFTA in each NAFTA country. When asked what country had benefited most from NAFTA, Mexicans responded that Americans had benefited most, Americans that Mexicans had benefited most, and Canadians that Mexico and the U.S. had benefited most. According to Professor Esquivel, “everybody is happy with NAFTA, but everybody thinks others have reaped the benefits of NAFTA mostly. [… We are moving] from the economics of NAFTA to the political economy of NAFTA.”

Professor Esquivel stated that back in the 1990’s most people believed Mexico would benefit most from NAFTA, simply because Mexico was the most impoverished of the three countries. But, for Mexicans, reaping the benefits of NAFTA meant improving living standards, not merely increasing trade and foreign direct investment. There is no doubt that the latter two have increased in Mexico with NAFTA, Esquivel acknowledged, but NAFTA “has not fulfilled its promises of development for Mexicans.” One would have expected that GDP per capita and GDP per person employed would converge among the NAFTA countries, but they have not. There has been no convergence. Instead, there has been a stagnation of income and a decrease in productivity for the Mexican people. The basket of goods available is much wider than it used to be, but Mexico has grown at a smaller rate than the rest of Latin America that does not have NAFTA. This does not mean that Mexico’s follies are the result of NAFTA, Professor Esquivel clarified. The lack of convergence may be explained because Mexico has not taken other steps that it needs to take to enhance the benefits of NAFTA. To conclude on this point, Professor Esquivel compared the distribution of value added in global manufacturing between capital and labor in Mexico. “Today, close to 70% of all the value added goes to capital, and just one-third goes to labor, which used to be 50/50. Just to give you an idea, in the US the distribution of value added between capital and labor is exactly the opposite. Two-thirds to labor, one-third to capital.”

Simon Lester, Trade Policy Analyst at Cato Institute took the floor next, and proposed to evaluate NAFTA within the sphere of three different lenses: as an international relations exercise, as a set of policies that liberalize trade, and as set of institutions. According to Mr. Lester, on balance, NAFTA had been positive in relation to the first two, but not necessarily the last. NAFTA suffers from a lack of institutional support. In contrast, the agreement brought the countries closer together and removed almost all tariff barriers. There have been job losses and some people have had to suffer the negative economic consequences, but similar effects have resulted from various other policy changes. The marketing of NAFTA was unrealistic, but generally speaking, trade liberalization made us better off.

The last speaker was Mark Weisbrot, Co-Director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research. Mr. Weisbrot reminded the audience that NAFTA had originally come into the scene unscathed, and that only after years of having voices of the likes of Joseph Stiglitz, Paul Krugman, and Jeffrey Sachs educate the public, had the agreement’s supporters been “defeated.” Turning to Mexico, Mr. Weisbrot went over the reason why, from the point of view of the majority of its people, NAFTA had been a bad deal. In particular, he pointed to the fact that the poverty rate in Mexico had not meaningfully decreased since its entry into force. Mr. Weisbrot had a lively exchange with Mr. Yerxa about the economic effects of NAFTA in Mexico.

Panel 2 – Wither NAFTA 2.0?

The second panel explored the negotiating positions of the US, Canada, and Mexico, and encouraged panelists to analyze the priorities for each country. It was chaired by Jennifer Hillman, Professor at Georgetown University Law Center, who asked the panelists to assume the role of “marriage counselor.” “Imagine what should a NAFTA 2.0 look like. If we could achieve a better NAFTA, what is it?” inquired Professor Hillman.

Chad Bown, Senior Fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics jump-started the conversation by making the case that NAFTA should be modernized, including by incorporating electronic commerce and digital trade, eliminating existing barriers to trade in agriculture, and updating the “draconian” rules of origin governing trade in autos. According to Mr. Bown, the TPP provided a suitable blueprint. Mr. Bown also spoke favorably of chapter 19 and criticized the current administration’s strategy of dictating the terms of the negotiation by reference to existing trade imbalances. He added: “you can try [that approach] if you are a state driven economy where the government decides how much to buy and sell from what countries, but in a market economy you can’t dictate what the trade balances are actually going to be.”

Melinda St. Louis, Director of International Campaigns at Public Citizen’s Global Trade Watch, followed and mentioned several proposals for improving NAFTA. These included eliminating investor-state dispute settlement, intellectual property rules that drive up the costs of medicines, and putting in place strong and binding labor and environmental standards. Ms. St. Louis repeatedly criticized how much weight corporate interests had been given in the original NAFTA negotiations. “NAFTA really must be replaced to correct the massive imbalance between corporate interest and the public interest.” However, “we don’t expect that what is on the table from the Trump administration is going to go in [that] specific direction,” she added.

Debra Steger, Professor at the University of Ottawa provided the Canadian perspective. She expressed that the NAFTA had been working well for Canada and that the agreement should be modernized and improved rather than rolled back. Canada should seek to improve the provisions relating to rules of origin, expand the commitments on government procurement, provide more coverage for temporary entry, and guarantee the right to regulate in the public interest, especially in relation to investment. Canada should, and has already insisted, that disciplines governing the environment, labor, gender equality, and indigenous rights be built into a NAFTA 2.0, a position that Professor Steger fully supported. It was evident from Professor Steger’s response that the TPP and the Canada-EU Agreement (CETA) provided an excellent benchmark for Canada in the renegotiation of NAFTA.

The Mexican perspective was represented by Antonio Ortiz Mena, Senior Advisor of the Albright Stonebridge Group. This perspective mirrored that of Canada in many respects. Mr. Ortiz Mena emphasized the modernization of the agreement in relation to rules of origin, trade in services, and government procurement, but he also drew some red lines: the elimination of the safeguard exception and chapter 19, and the sunset clause. Finally, Mr. Ortiz Mena also noted that labor discussion within NAFTA should not encroach upon a country’s levels of wage.

Professor Hillman then asked panelists to comment on the issues that would justify withdrawing from NAFTA and elicited some original responses. For example, Melinda St. Louis of Global Trade Watch cast the limelight on the agreement’s approval process. She posited that if the Trump administration was not able to secure a significantly different NAFTA that incorporated the changes that the consumer and progressive base demanded, it would not be able to get a majority of Congress to pass it. She also commented that “no NAFTA” would be better than the “status quo,” an opinion that Professor Steger said would not be shared by Canadians, because the neighbors to the north continue to be very much in favor of NAFTA. Encouraged by a follow-up question raised by Professor Hillman, Chad Bown spoke more broadly about the economic implications of a withdrawal from NAFTA. He observed that the biggest losers from a withdrawal from NAFTA would be those in the private sector with supply chains that are highly integrated (e.g. automobiles and electronics).

Keynote

Karen Antebi delivered the keynote address for the event. She provided a quick glimpse into the Mexican government’s position, both in light of its legacy and in consideration of the Mexican government’s decision to renegotiate. As several morning panelists had anticipated, the official Mexican stance was to look back at the last 23 years in very positive terms, and to promote the case of free trade. Mrs. Antebi highlighted how trade and foreign direct investment had increased since the coming into force of the agreement.

She also emphasized how there had been macroeconomic stability in Mexico (despite the low levels of GDP growth), and how the countries involved, especially the US and Mexico, had become interdependent. Finally, Mrs. Antebi also remarked that a NAFTA 2.0 should be buttressed upon four pillars: (i) strengthening the competitiveness of North America; (ii) establishing a more inclusive and responsible regional trade; (iii) addressing the 21st century economy, and; (iv) providing certainty for investment.

Panel 3 – Domestic Measures to Bolster NAFTA

The third and final panel was moderated by Matthew Carnes, Director of CLAS and Professor at the Georgetown University Department of Government and School of Foreign Service. Professor Carnes asked the panelists to think about how the gains of trade may be better spread. He invited the panelists to think of this issue “domestically,” with each of the countries and groups they represented in mind. “How might we think about compensating those who have lost in the process of economic integration and those that have lost jobs or seen their wages decline, and how might they better participate in the game?” inquired Professor Carnes.

Dany Bahar, Fellow at the Brookings Institution took a first shot at the question by describing the dynamics of trade policy in the context of the US economy. “The theory says that within each country there are going to be winners and losers […] We take a share of the pie that the winners are winning and then give it to the losers.” Judging by the result of the last election, Mr. Bahar pointed out, “that clearly didn’t happen in the US.” He also added that providing the social protections that the losers need as a result of trade transformations was not something that could be dealt with at the negotiating table.

Celeste Drake, Policy Specialist at AFL-CIO, disagreed with that statement. She noted that the distributive impact of trade is much larger than the impact that arises from job losses, and that there are no legal rules to offset the benefits that are given to those who are already on top. Instead, agreements like NAFTA have rules that limit domestic policy choices. These rules penalize countries on the basis of how they regulate their banks, how they use fiscal policy to stimulate job growth, or how they promote green energy. In Ms. Drake’s view, trade agreements should build in commitments (such as domestic infrastructure commitments) that expand domestic policy choices and shift the distributional outcomes of trade.

Edward Alden, Senior Fellow at Council on Foreign Relations and author of the book “Failure to Adjust: How Americans Got Left Behind in the Global Economy,” spoke more directly as to measures to be taken on the domestic front. He drew attention to the fact that much of the social safety net in the US is linked to full-time employment. Vacation time, retirement benefits, and health insurance are all benefits that are given because of employment. But full-time employment is declining. More people are working on a contingency and part-time basis. According to Mr. Alden therefore, the benefits system needs to be redesigned to account for the way workers are employed today.

The last panelist to take the microphone was Mario Delgado, Mexican Senator belonging to the progressive MORENA party. After speaking to some of the effects of trade in Mexico for the last 23 years, Senator Delgado provided a set of domestic policy prescriptions. He suggested that investing in human capital and innovation, linking wages to productivity, connecting more companies to the export sector, pursuing an aggressive industrial policy, and conceiving a regional development strategy, were among the policy measures that needed to be taken in order to offset the negative effects that result from an agreement like NAFTA.

Following a second round of interventions, Dany Bahar offered a word of caution with respect to reducing inequality via subsidization. Subsidization (or dumping) as a strategy for development, Mr. Bahar posited, could entail “punishing the poor countries that don’t have the money [to subsidize their firms], or punishing the small firms without enough cash flow to do dumping.” Edward Alden then continued with inequality as a theme. He emphasized that globalization and technology are in effect labor substitutes and that they have tended to increase inequality. If one is too look at countries where inequality is not growing rapidly, those are places that have had policies in place to offset it. Having those policies “is particularly hard for the United States,” Mr. Alden noted, because historically, “the U.S. has not been a very trade dependent country.” Finally, Senator Delgado added some concluding remarks by noting that what Mexico needs to decrease inequality are policies that offset wage stagnation and that strengthen the fight against corruption.