Justice for Ukraine: Georgetown Law Partners with Ukrainian Prosecutors

May 31, 2024

Residents of Zaporizhzhia, Ukraine survey Russian airstrike damage to their apartment building. Photo: Elena Tita/Collection of war.ukraine.ua

The morning before Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, former U.S. Ambassador-at-Large for War Crimes Issues Clint Williamson woke up to a flurry of messages.

It was the office of the Ukrainian prosecutor general.

Up until the eve of the invasion, most Ukrainians had considered the prospect of all-out war to be quite remote. But as Russian troops gathered on the border, the Ukrainian prosecutors understood that something terrible was about to unfold.

“They were clearly rattled,” Williamson, who retired from the State Department in 2014 and is now Senior Director of the International Criminal Justice Initiative (ICJI) at Georgetown Law, recalled. “The then-Prosecutor General asked me if I could come immediately to Ukraine and, as she said, ‘show us how to do this.’ She knew that they were about to be inundated with potential war crimes.”

That day, from his home in Washington, Williamson began assembling a team of experts and working with the State Department to get them on the ground. They deployed to the Polish-Ukrainian border eight days after the Russian onslaught and met with Ukrainian prosecutors the following day, launching a collaborative operational relationship that has continued unabated since that time. This initiative would evolve into what’s now known as the Atrocity Crimes Advisory Group for Ukraine, or ACA, jointly supported by the United States, the European Union and the United Kingdom.

Under Williamson’s leadership, Georgetown Law’s new International Criminal Justice Initiative has become the lead implementer of ACA, coordinating international support for Ukrainian prosecutors. Georgetown’s work began in earnest in October 2022 with an initial $10 million grant from the U.S. Department of State. A further $8.5 million was recently allocated to continue this work through late 2025.

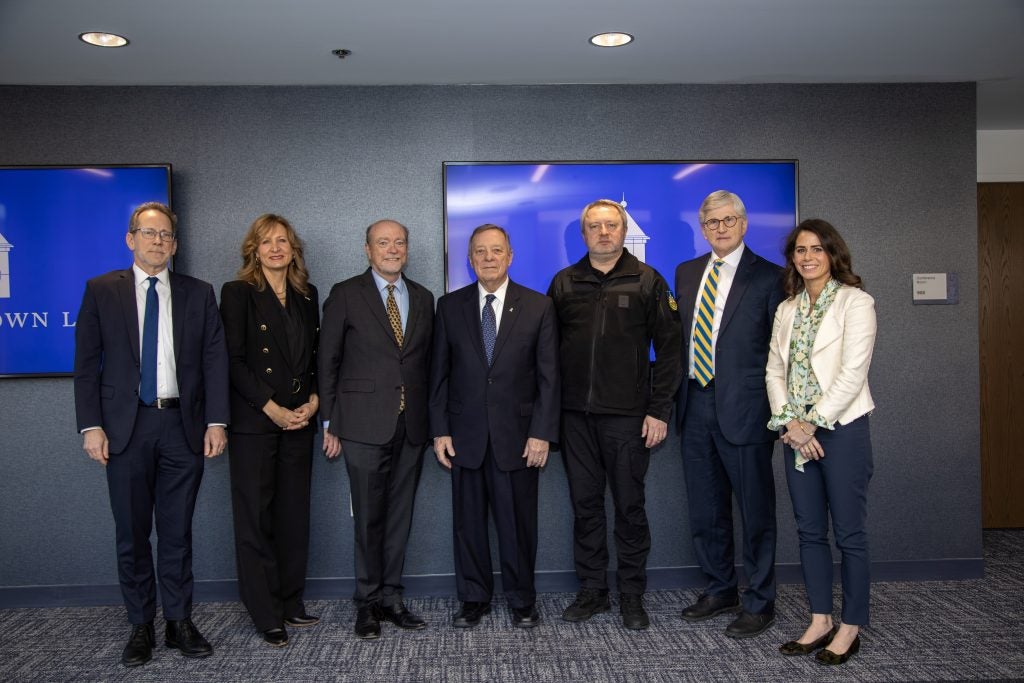

In 2023, Georgetown Law hosted an event with Ukrainian Prosecutor General Andriy Kostin. L-R: Williamson, U.S. Ambassador-at-Large for Global Criminal Justice Beth Van Schaack, Dean Treanor, Sen. Dick Durbin, F’66, L’69, Kostin, Prof. Mitt Regan, L’85, Center on National Security Executive Director Anna Cave

The work that the ACA-Georgetown team is doing in Ukraine is unprecedented. Normally this sort of work would be done by an international organization, such as the United Nations. But international consensus around such traditional approaches is increasingly elusive. ACA represents a true innovation in international justice, a novel model for seeking accountability and justice in conflict. At the same time, Ukraine’s Office of the Prosecutor General is also paving a new path: taking the lead role in developing an atrocity crime prosecution strategy for its own country, even as the conflict continues to rage.

Georgetown Law faculty, staff, fellows and students are marshaling a team of multidisciplinary experts, organizing legal and other resources, providing robust practical support and assisting the Ukrainians in developing an effective atrocity crimes investigation and prosecution process. The growing ACA team of staff and consultants hails from around the globe, including the U.S., France, Canada, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Germany, Italy, Portugal and Finland. Williamson, who worked with many of these experts in past prosecutions, said, “We are truly

enlisting the best of the best. Cumulatively, the team brings over 325 years of experience in atrocity crimes work. We are making a huge impact on a day-to-day basis. This is Georgetown at its core, putting into practice its ethos of advancing social justice and making a positive difference in the world.”

Displaced Ukrainians in the Lviv train station

Since the beginning of the full-scale Russian invasion, thousands upon thousands of Ukrainian lives have been lost, and the Ukrainian prosecutor general’s office has opened more than 125,000 potential atrocity crime cases. In clear violation of international law, Russian forces have targeted Ukrainian civilians throughout the conflict, launching missiles at residential buildings, hospitals and schools, deporting children and more.

The challenge facing Ukrainian prosecutors is to pivot a system meant for ordinary peacetime criminal cases towards a system to pursue justice for mass atrocities in wartime.

“They know how to prosecute crimes. What they need help with is the specific expertise,” Williamson said. “So this is what we’ve been trying to do: take the experience from working in international tribunals or in domestic systems where they’ve done war crimes cases, and bring that to bear on the ground in Ukraine.”

Ukrainian leaders welcome the support. In March of this year, Ukrainian Prosecutor General Andriy Kostin posted a photo of himself and Williamson standing side by side on social media, with the comment “Grateful to Ambassador Clint Williamson for his unwavering support for Ukraine in these difficult times. In Kyiv, we discussed our continued cooperation with the Atrocity Crimes Advisory Group and Georgetown Law experts. Their practical and timely assistance is invaluable to our justice and accountability efforts.”

Those involved in the Georgetown project ticked off the unique assets that the school brings to address this enormous problem: the university’s long track record of ambitious international projects, a deep bench of faculty with extensive experience working in government or international bodies and, of course, the location in the U.S. capital.

With these tools at its disposal, the Georgetown initiative under the ACA framework is prepared to help the Ukrainian justice system for the long haul.

“This is a marathon. It’s not a sprint. You’re going to be dealing with these cases for decades,” Williamson predicted.

A MONUMENTAL TASK

Given the unprecedented nature of the Ukrainian-ACA partnership, there is no existing road map in place. The ACA advisors have decades of expertise, but don’t know the country’s history, legal system, politics and culture like the Prosecutor General’s team does. On the other hand, Ukrainian prosecutors know their own country, but have never had to make decisions about which mass execution to prioritize dedicating investigative resources to, the way veterans of past tribunals have. It’s a multilayered process of building trust with partners at ministry headquarters in the capital city as well as with regional prosecutors in places like Dnipro, Odesa, Mariupol—Ukrainian towns and cities whose names now bring brutal images to mind. To date, ACA has carried out more than 100 field missions to 15 regions across Ukraine.

ICJI-ACA Chief of Staff Kip Hale (center, bearded), meeting with ACA colleagues and prosecutors from Luhansk, Ukraine in Dnipro, Ukraine

Many of those meetings are led by Williamson’s chief of staff, Christopher “Kip” Hale, another veteran of conflict-related investigations and litigations. Two decades ago, when he was a student at the University of Denver Sturm College of Law, he heard a talk by an international tribunal prosecutor that set him toward that career path. Since then he’s worked on investigations and prosecutions in the former Yugoslavia, Cambodia, Afghanistan, Syria, Iraq, Myanmar and Libya – other places with bitter histories of war and civilian casualties.

“What are the things that you can investigate the best, and where can you have the greatest chance of prosecution success? And then also mixed into that is all sorts of factors. What has been the biggest impact on the population? What has been harming them the most? What are the gravest criminalities?” says Hale, running through just a few of the complex discussions he’s been having. “There’s a lot of this kind of translation that has to happen, not just language translation, but translations of cultural expectations and mores.”

Ukrainians may want any number of things in addition to or in lieu of prosecutions: reparations; truth-telling about the perpetrators or information-gathering about missing loved ones; memorialization of those whose lives were lost; security guarantees to reduce the chances that war will occur again – all of those things on top of the traditional pathway towards criminal accountability: prosecution, trials and convictions.

This is far from the only novel approach the Georgetown-led project is adopting. They’re tapping into a wide array of fields to facilitate justice: gathering psychologists to help build systems to aid witnesses and victims that cooperate with prosecutors, for example, and environmental experts who can assess ecological damage brought about by the war, and cyber specialists who can look at how Russia may be committing crimes in a new domain.

Georgetown’s initiative – through ACA – is hoping not only to lend assistance to Ukraine, but also to create a new model that combines all of the best practices for how to set up a system that brings accountability for atrocity crimes and how to provide international support to domestic jurisdictions doing the work.

“This is a monumental task, and ACA is the first salvo in trying to help Ukrainians set themselves up for ultimate success, but it requires realizing that unfortunately, the vast majority of their defendants are on the other side of the front line, and they’re not getting arrested anytime soon,” Hale said. “It is very hard to tell Ukrainians to manage their expectations that way, because it doesn’t bring solace or immediate relief to the thousands of victims.”

What keeps Hale going? The people he’s working with, he says. “My colleagues are just so great. The egos are checked at the door, they want to help. They are patient, they are competent, they are easy to work with.

“And so there is a lot to be inspired by, but it is a monumental task.”

STRATEGY SESSION

Commercial flight into Ukraine is impossible due to the war, which makes the trip into Kyiv a multi-day journey involving flights to Poland followed by a 12-hour drive. Every several weeks, Hale, Williamson, or other ACA-Georgetown leaders undertake the long trip to meet with members of the prosecution team.

Many Kyiv landmarks, like the Princess Olga Monument, left, have been surrounded by sandbags to protect them from airstrikes.

Even under frequent air raids, the city remains a bustling metropolis, with a vibrant street life befitting its early history as a trading post on a river route from Scandinavia south to modern-day Turkey.

At one joint meeting last summer, the lights in the hallways are off, a reflection of energy saving measures that are in place — itself the result of the alleged atrocity crimes involving Russian attacks on Ukrainian civilian energy infrastructure.

The lawyers huddle around a long conference table in a bare, humble, white-walled room marked with little more than EU and Ukrainian flags. Notebooks out, pens flutter as the whole team takes notes.

This particular meeting is on how Ukrainian lawyers might take in victim statements as they compile atrocity crime evidence. The topics are as fascinating as they are broad: how to take testimony in territories currently occupied by the Russian military, and how to protect witnesses who provide sensitive information.

And then there are the more mundane, but no less important, pieces of advice that are exchanged: how to organize the legal teams and divide responsibility for prosecutorial tasks in the most effective way, for example; and how to organize specific technical training for Ukrainian lawyers.

The advice the ACA team gives is earned from cumulative decades in the study and practice of international criminal law and related fields. It’s not only a reminder of the long history of this legal topic, but a sad reminder that other countries have also gone through this terrible process before, and learned hard-fought lessons.

NOT ALONE

Davorka Čolak, a Croatian citizen and career prosecutor, traveled first to Kyiv as part of the Georgetown-led team in the summer of 2022. She’s now working with the ACA team as co-coordinator of all Georgetown’s experts.

Croatia has its own terrible experience, and has spent some thirty years trying to bring justice for atrocity crimes that happened during the Yugoslav Wars.

ACA’s Davorka Čolak, center, speaking at a Georgetown Law event with colleagues Ingrid Elliott, left and Irisa Čevra, right

“I’m not here to tell [the Ukrainian government] what to do,” Čolak said. “I’m here to share my experience in all the mistakes that we made so they can be avoided.”

She advised the Ukrainians to centralize data for preservation and prosecution, for example. Her most important piece of advice is a sobering one.

“Collect and preserve your evidence as much as you can, because this is not going to be a year-long or five-year process,” she said. “You will need that evidence in thirty, forty years. So the best thing you can do right now is collect and preserve your evidence.”

She’s also told them of the need to have highly trained, specialized investigators dealing with atrocity crimes.

“And they already did it,” she said, “They already designated nine regional offices to be specialized offices.”

Čolak’s personal experience injects a morale-boosting camaraderie, a terrible yet useful understanding that Ukrainians are not alone in their struggle. The Croatian experience demonstrates that other domestic systems have successfully been able to bring about some measure of justice for atrocities.

Čolak and other ACA leaders have given Ukrainian prosecutors the opportunity to see with their own eyes some of the places they’ve been hearing about as examples. On one trip, they traveled to Vukovar, Croatia, which suffered a monthslong siege in 1991. The group visited the Ovčara memorial site commemorating the mass killing of prisoners of war and civilians. Colak recalled seeing her Ukrainian colleagues in tears at what they were seeing.

“They said, ‘Thank you for helping us realize that this is an ongoing process, that it’s not ending in a year or two,’” said Čolak.

When asked a question on the mind of many Ukrainians: Is a war over when the fighting ends, or when justice is achieved for the wrongs done? – she began describing a special database in Croatia that stores all the evidence collected from their war.

“We were thinking, if we keep it separately… nobody in a hundred years will be able to manipulate the data, to manipulate the history,” she said.

“When is the war over? I don’t know. I don’t have an answer.”

LIVING HISTORY

Since Georgetown Law became involved with this project a year and a half ago, it has tapped into the university’s pool of alumni, adjuncts, fellows and faculty. The Georgetown Law Center on National Security and especially its executive director, Anna Cave, and faculty co-director, Professor Mitt Regan, L’85, played key roles in its early stages. More recently, in late 2023, professors in the Law Center’s Legal English team hosted a group of staff from the Office of the Prosecutor General for an intensive five-week course in both American legal vocabulary and the overall structure of the U.S. legal system.

Staff from the Office of the Ukrainian Prosecutor General came to Georgetown Law for a special course in Legal English. L-R: Siuzanna Savchuk, Yuliia Usenko, Veronika Plotnikova, Prof. Julie Lake, Oleksii Boniuk, Prof. Heather Weger, Viktoriia Litvinova

Dean William M. Treanor sees the project as an embodiment of what Georgetown Law is all about. “It gives the law school a chance to take the lead in advancing justice on the world stage, provides students with an extraordinary experiential learning opportunity and gives faculty the opportunity to advance cutting-edge research on international peace and security,” he said.

Georgii Grygorian, L’23, served as a research assistant for ACA while he was still a student. He is a Ukrainian who began studying for his LL.M. at Georgetown Law in the fall of 2022.

While at Georgetown, he received terrible news: his home had been destroyed by a Russian drone attack in Kyiv. His father had been at the residence just fifteen minutes before the strike, but thankfully left right before the attack occurred.

“I lost everything I had in Ukraine,” Grygorian said. The attack had taken place near the offices of Ukraine’s electric grid operator in Kyiv, so his apartment had been lost in an attack that itself is arguably an atrocity crime – the targeting of civilian energy infrastructure during a time of war.

The incident helped inspire him to join ACA and help with the ongoing legal effort to bring justice for crimes like these. He said he wanted to “make a difference and to protect the Ukrainian people” by bringing best practices from history to his home country.

“We need to work very hard, and to take every single example from history that we know, and to implement all of these doctrines, ideas and similar cases,” Grygorian said.

Hale hopes that the groundwork the ACA-Georgetown team is laying will ultimately benefit not only the Ukrainian people, but will guide lawyers through the aftermath of conflicts yet to come. It’s a lesson he says he learned from one of his mentors, Benjamin Ferencz, who prosecuted Nazi leaders at the post-World War II Nuremberg tribunals and passed away only last year, at age 103. Ferencz loved to tell the story of the Renaissance-era Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe, whose charts of the heavens were used more than three centuries after his death by NASA scientists planning the moon missions.

“Progress happens over generations,” says Hale. “So to use an American football analogy, I’m just trying to get this ball further down the field so that one day, no matter where atrocity crimes happen, be it in Ukraine, be it in Palestine, be it in Sri Lanka, be it in North Korea, be it in the United States, that it will always be investigated and where warranted, prosecuted. We’re not there yet. But I feel that I’m doing my part to push that forward.”

Click here to follow ICJI/ACA’s ongoing work.

Author Tim Mak, an investigative journalist, is based in Kyiv, Ukraine. He has reported for NPR, Politico, The Daily Beast and other outlets and is a former U.S. Army combat medic. You can follow his work at counteroffensive.news.