Policy Brief: World Trade Organization Monitoring Function at a Global Trade Turning Point: Expectation for the 2024 China Trade Policy Review

Published June 10, 2024 by Sae Kobayashi, Class of 2023 at Georgetown Law, IIEL Fellow

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are my own and do not reflect the views of my employer.

I. Introduction

The international trading system is at a turning point. A shift from multilateral towards regional and like-minded countries’ frameworks is an undeniable fact. Each state is also facing an urgent need to rebalance trade policies in light of geopolitical risks. Since 1995, Regional Trade Agreements (RTA) have flourished, [1] including notable ones like the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) [2] and the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). [3] Now, the world has witnessed non-traditional and flexible trade cooperation mechanisms such as the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF)and the US-EU Trade and Technology Council. These new frameworks aim to foster a resilient, sustainable, and competitive economy, while also leveraging the rule-based multilateral trading system (MTS). Nevertheless, questions have arisen regarding the compatibility of some unilateral measures that primarily pursue national interests such as the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism and the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act, with international economic law. Moreover, economic coercion, export controls and investment restrictions on emerging technologies have now risen to prominence within trade policies, driven by national security concerns. [4] At the same time, three decades since its establishment, numerous concerns about its efficacy in navigating contemporary challenges are looming over the World Trade Organization (WTO). These concerns stem from a weakened negotiation function and a stalled dispute settlement mechanism, both of which were poorly addressed in the recent Ministerial Conferences, despite some progress.

Given this trade landscape, this article emphasizes the increasing significance of the monitoring function of the WTO, with a particular focus on the Trade Policy Review (TPR) of China, previously held in 2021 and to be repeated this summer. The Trade Policy Review Mechanism (TPRM) serves as a valuable tool in empowering the WTO and the MTS to effectively tackle contemporary challenges and fulfill global expectations.

II. WTO Trade Policy Review Mechanism

The TPRM is one of the main monitoring works at the WTO. It is a peer-review mechanism applicable to all Members set out in Annex 3 to the Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the WTO. Annex 3 delineates its objectives as “contribute to … the smoother function of the MTS by achieving greater transparency in, and understanding of, the trade policies and practices of Members.” [5] Under the TPRM, the top four players by their share of global trade (currently China, the EU, Japan and the U.S.) undergo review every three years, while the next sixteen are reviewed every five years and the remaining members every seven years. [6] Each review consists of the submission of two documents (a Secretariat report written by the WTO Secretariat’s Trade Policy Review Division and a government report written by government officials from the country under review) along with questions and replies resulting from a two-day meeting. Importantly, the scope of the review is not limited to the WTO Agreement, but covers “the full range of individual Members’ trade policies and practices and their impact on the functioning of MTS.” [7] In addition, Annex 3 clarifies that TPR is not a basis for the enforcement of obligations under the Agreement or dispute settlement procedures, or to impose new commitments. [8]

III. China TPR

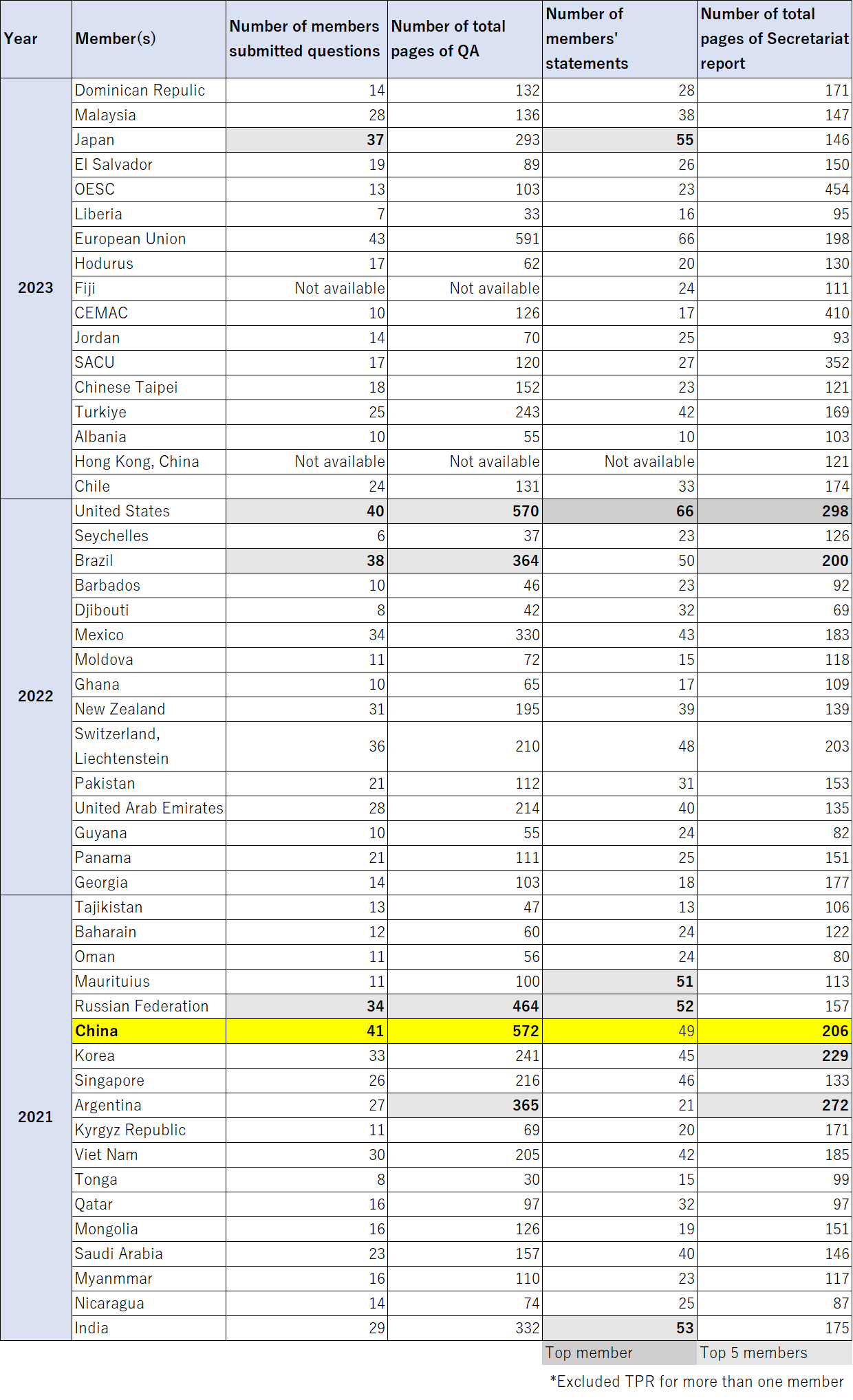

The China TPR is undoubtedly a high-profile meeting. It serves as the venue for enhancing understanding of China’s trade policies. Recently, China’s review has become somewhat contentious through the active participation of Members. China’s most recent review was held in October 2021 and the next review is scheduled in July 2024. Chart 1 shows uniquely active engagement by Members in China TPR. China received the largest number of questions during 2021 to 2023 and as many as forty Members submitted questions regarding China’s trade policies.

The last China TPR mirrored real-world geopolitics, as evidenced by the polarized perspectives of Members’ statements toward China’s trade policies. [9] Western countries and some other Members such as Mexico and Brazil harshly criticized China’s claim to developing country status, transparency, and industrial subsidies. For instance, the U.S. stated that “WTO members expected that the terms set forth in China’s Protocol of Accession would permanently dismantle exiting Chinese policies and practices… But those expectations have not been realized and it appears that China has no inclination to change.” Australia stated “China has increasingly tested global trade rules and norms by engaging in practices that are inconsistent with its WTO commitments.” China vigorously responded against its critics. [10] In contrast, a large number of developing and emerging countries were pleased with China’s remarkable economic growth and echoed appreciation for its economic cooperation as one of their main trading partners. There is a long list of such Members including Russia, Philippines, Viet Nam, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Argentina, Chile, and Zimbabwe.

Several media outlets covered this meeting, mainly intrigued by the intensifying US-China trade relationship. POLITICO reported, “The United States and other countries accused China of undermining the rule-based global trading system through its massive use of industrial subsidies and other practices, as the world’s second-largest economy approaches the 20th anniversary of its entry into the WTO.” [11] The South China Morning Post highlighted China’s comment that “much of the criticism (at WTO periodic review) should not be taken as fair assessment but a “wish list” for China” and explained “the tone at the meeting was far sharper than the last review in 2018, showing how far the political mood between China and key Western trading partners has soured in recent years.” [12]

Last but not least, the Secretariat report also delved quite deeply into the subject matter corresponding to these interests as a member-driven organization. For example, due to the increased attention on China’s subsidy, one section in the 2021 China TPR report compiled self-sourced data of non-notified government guidance funds, where the report says “According to the (Chinese) authorities, these funds are not required to be notified under the SCM Agreement as the support provided through these funds does not constitute subsidies.” [13] This deeper research and inquiry helps Members to understand the better shape of China’s subsidy beyond self-notified information.

IV. Prospect for Utilization of TPR

It is essential to acknowledge and utilize the monitoring function of the WTO to ensure the relevance of the MTS to contemporary challenges, especially in light of the current difficulty in creating binding obligations in multilateral fora. Even amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the WTO monitoring function remained active and delivered updated information on emergency trade-restrictive measures, which greatly aided states in making informed decisions. [14] Nevertheless, it took time for rule-making regarding these measures. [15]

The next China TPR will be held in July 2024 and will serve as the perfect venue for Members to obtain information and voice their concerns and requests regarding China’s trade practices. Critics have denounced the decision to support China’s accession to the WTO 23 years ago. [16] However, that may miss the point. The WTO is aiding the policy-making of individual states and collaborative initiatives through monitoring, along with facilitating the formulation of substantial obligations. Although monitoring does not directly change states’ policies and behaviors, given the current systemic challenges facing the WTO, it is even reasonable to argue that the monitoring function is currently the most powerful tool.

This article will conclude with prospects for the upcoming China TPR. First, Members are strongly encouraged to utilize this opportunity to express their concerns, requests, and appreciation. In response, China is also expected to sincerely hear these voices and provide information to ensure transparency. It is unreasonable to answer “it is outside of TPR” because Annex 3 does not limit the scope of TPR to the WTO Agreements and emerging issues potentially outside the scope of the WTO Agreement would be the main concern of other Members. Simultaneously, the Secretariat has a responsibility to provide up-to-date first-hand information to facilitate active participation, especially through country visits, and can collaborate with other international organizations to collect data. For instance, information on subsidies related to state-owned enterprises and the evolving landscape of cybersecurity and data regulation will be notable subjects in the next meeting. Moreover, the Secretariat and Members can connect the outcome of the TPR to discussions in other for such as G20 and OECD. The utilization of the next China TPR will empower all Members to pursue their national interests while also reinforcing MTS.

V. Chart 1 Members’ Engagement in TPRs in 2021, 2022 and 2023

Source: Compiled by the author based on the WTO website data.

The author would like to express her gratitude to Professor Jennifer Hillman (Georgetown University Law Center) and Jesse G. Kreier (Former Acting Director, WTO Rule Division, Adjunct Professor of Law) for their advice on the article.

Sources:

[1] WTO website, Accessed on April 13, 2024. https://rtais.wto.org/UI/PublicMaintainRTAHome.aspx

[2] The Member contains Asia-Pacific countries of Australia, Brunei, Cambodia, China, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, New Zealand, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam.

[3] Starting from 8 countries of Cameroon, Egypt, Ghana, Kenya, Mauritius, Rwanda, Tanzania, as of 2023, 47 countries ratified the AfCFTA.

[4] The EU framework for investment screening was fully implemented in October 2020. The U.S. introduced outbound US investment restrictions to China on semiconductors, quantum technologies, and AI in August 2023. China bans exports of technologies for processing rate earths in December 2023.

[5] Annex 3 to the Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the WTO, A(i).

[6] Id.

WT/TPR/6/Rev.4.

[7] Id.

[8] Id.

[9] All members’ statements are available at WT/TPR/M/415 pp.14- 72.

[10] For instance, in the second day opening statement, China clearly denied forced technology transfer and forced labor as well as providing additional explanation on SOEs, subsidies and overcapacity. (WT/TPR/M/425 pp .73-77)

[11] Doug Palmer, WTP members blast China during 20th anniversary trade policy review, POLITICO, October 21, 2021.

https://www.politico.com/news/2021/10/21/wto-china-20th-anniversary-trade-policy-516647

[12] Orange Wang, China takes aim at US and its allies over ‘unreasonable’ claims at WTO trade review, South China Morning Post, October 29, 2021.

https://www.scmp.com/economy/china-economy/article/3154036/china-takes-aim-us-and-its-allies-over-unreasonable-claims

[13] WT/TPR/S/415 p. 77 3.3.1. Incentive

[14] WTO website updated and organized COVID-19 trade-rerated measures and support measures based on Member-provided and self-researched information.

https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/covid19_e/covid19_e.htm

[15] For example, the Ministerial Decision on a waiver of intellectual property protection for COVID19 vaccines was adopted in June 2022. It was at the end of March 2020 when G20 agreed “Emergency measures aimed at protecting health will be targeted, proportionate, transparent and temporary” regarding assessing international trade disruption.

[16] For example, 2018 Report to Congress on China’s WTO Compliance by the United States Trade Representative published in February 2019 states “the United States errored in supporting China’s entry into the WTO in terms that have proven to be ineffective in securing China7s embrace of an open, market-oriented approach to the economy and trade.”

https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/2018-USTR-Report-to-Congress-on-China%27s-WTO-Compliance.pdf