Policy Brief: Echoes of the Past: The Impact of Japanese Colonialism on Commercial Diplomacy in East Asia

Published July 8, 2024 by Zainab Ahmed, Interim Executive Director at the Institute of International Economic Law

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are my own and do not reflect the views of my employer.

I. Introduction

The relationship between Japan and South Korea has long been rife with conflict dating back decades to Japan’s occupation of the Korean peninsula and war crime atrocities. Despite diplomatic relations being established in 1965, the South Korea government, civic groups, victims, and citizens continued to push for restitution, leading to tense relations between Japan and South Korea that escalated into a trade dispute in July of 2019, where economic and security concerns were weaponized to address unresolved historical grievances between the two countries.

This policy brief surrounds a case study of the 2019 Japan-South Korea Trade Dispute and the question of how war memory impacted semiconductor supply chains, exploring how the emerging and escalating diplomatic challenges surrounding Japan’s colonial rule in Korea led to the 2019 trade dispute.

II. Historical Context

Japan’s quest for wealth and power overseas began in the late 19th century following Japan being saddled with unequal treaties devised by European powers starting in the 1850s. [1] The Meiji oligarchs dreamed of establishing a “European-style Empire on the edge of Asia” to transform the Japanese Empire and the Japanese people to be more like those of Europe. [2,3] The Korean peninsula lay at the heart of such ambitions, located a mere 120 miles from Japan, and a gateway to mainland Asia and Russia, the colonization of the peninsula was considered a matter of national security.

Replicating the treaties hoisted upon them by European powers, Japan signed a number of treaties with Korea including the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1876 which forced Korea to open up to trade and “cede its sovereign rights by granting Japanese nationals extraterritoriality and immunity to tariffs” [4] and Treaty of Shimonoseki in 1894 that forced the Korean government to expel any remaining Chinese military presence that could be used to rebuff Japan’s colonial advances.

Following the conclusion of the Russo-Japanese War, the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1905 was signed, stripping the Korean of its diplomatic independence as Itō Hirobumi took the position of Resident-General of the Korean peninsula and Japanese advisors were strategically placed in control of key areas of governance. [5] Two years later, the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1907 “gave Japan complete control over Korea’s diplomatic affairs, signaling its de facto annexation of the peninsula”. [6] It was not until August 15, 1945, following the end of World War II, that Korea was liberated from 35 years of Japanese colonial rule, and for a brief moment, the Korean peninsula was united. [7,8]

III. Japanese Colonial Policy in Korea

Japanese colonial policy in Korea can be defined by three distinct time periods – pre-annexation policies focused on transforming Koreans into loyal Japanese subjects, assimilation policies during 1919-1920, and ethnocidal policies introduced in the late 1930s following independence movements and challenges to Japanese colonial powers by Korean nationalists. [9–11]

In the 1930s, the naisen ittai policy was introduced as a means to maintain security of the Korean peninsula. [12] The policy advertised Japan and Korea as one body (內鮮一體), forced Koreans to abandon their cultural identity and adopt a Japanese identity, a distinct shift from earlier colonial policies that sought to separate the “pure” Japanese people from being mixed with “inferior” Koreans. [13] With the naisen ittai policy, Japan waged an all out war on Korea’s cultural identity, land, and people. The Japanese colonial government destroyed Gyeongbokgung, the Korean royal palace, and many other historic buildings, with remaining buildings being turned into tourist attractions for Japanese settlers and visitors, with the distinct intention to advertise how “civilized” Japan was in comparison to the “primitive” Koreans. [14] Koreans were forced to worship at Japanese shrines, schools and universities were forbidden to teach in Korean, it was a crime to teach history that was not approved by the Japanese authorities, and Korean-language newspapers were shut down. [15,16] Japanese settlers claimed native Korean land with impunity and the mass murder of Korean citizens by Japanese settlers and the colonial forces was also prevalent throughout the occupation. [17–22]

Japan’s wartime mobilization brought further suffering as Korean men were drafted into the Japanese military; Korean citizens including children were forced to work in mines, factories, military bases, and in Japan and other colonies with little to no pay; and beginning in 1932, young Korean women and girls were forcibly sent to the front lines and confined to rape stations where they were sexually assaulted and tortured daily by Japanese imperial soldiers as part of the Japanese military sexual slavery system. [23–25]

In 1939, Japan also introduced sōshi-kaime, a policy that forced Koreans to take Japanese surnames by refusing to recognize Korean surnames, essentially locking those who opted to keep their native surname out of “everything from mail delivery to ration cards”. [26] In this way, Japan endeavored to systematically eliminate the Korean national identity and asserted complete domination. This final period was characterized by its brutality and continued until Korea’s independence in 1945.

IV. Emergence of a Diplomatic Challenge

Following Japan’s WWII defeat in 1945, the issue of Japan’s colonial era atrocities was buried for the next four decades. The Japanese government and military worked to destroy evidence resulting in a lack of publicly available irrefutable evidence, and the issue was notably not included in the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal nor the Treaty of San Francisco as the Allied powers worked to re-establish relations with Japan. [27] In 1965, 20 years after Korea’s liberation from Japanese colonial rule, Japan and South Korea signed the Treaty on Basic Relations that established diplomatic relations between the two countries, however, the issue of forced labor by private Japanese companies nor Japan’s military sexual slavery system were not discussed, leaving an open wound that would fester with time. [28]

Kim Hak-Sun was the first to come forward and publicly testify that she was a victim of the Japanese military sexual slavery system, on August 14, 1991, providing an international platform for other victims to come forward and share their stories. [29] Following Kim’s testimony, the Korean and international community began to actively report on Japan’s colonial era atrocities. In December 1991, Kim alongside two other victims filed a lawsuit in Tokyo District Court against the Japanese government demanding “an official apology; compensatory payment to survivors in lieu of full reparation of ¥20 million each; a thorough investigation of their cases; the revision of Japanese school textbooks identifying this issue as part of the colonial oppression of the Korean people; [and] the building of a memorial museum.” [30,31] However, it was not until Yoshimi Yoshiaki, a Japanese military historian, announced the existence of evidence proving the Japanese military’s involvement in the military sexual slavery system on January 10, 1992 that Japan began to address its colonial past. [32] In 1993, Japanese Chief Cabinet Secretary Yohei Kono offered a formal statement, known as the 1993 Kono Statement, to the victims of the Japanese military sexual slavery system, acknowledging the Japanese military’s involvement in the establishment of rape stations and the “recruitment” of victims. [33,34] With this statement, the Japanese government accepted moral responsibility for its war crimes, but refused to pay compensation to victims as it claimed that any legal claims were settled by the 1951 Treaty of San Francisco and the 1965 Treaty on Basic Relations. [35] Instead, the Asian Women’s Fund, a private fund consisting of donations from private citizens to compensate surviving victims of Japanese military sexual slavery, was established in 1995. [36] However, the establishment of the Asian Women’s Fund was rejected by survivors and the Korean Council for the Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery by Japan as they maintained that any apology and reparations should come directly from the Japanese government. [37,38] In 2001, a number of cases filed by victims of military sexual slavery and forced labor were dismissed, including the initial 1991 filing with the Court stating that “individual victims’ claims for damages against Japan were unacceptable under international law.” [39]

Prominent Japanese politicians have also undermined any semblance of restitution. In 2007, former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe stated in a Diet session that “there may be enforcement in mobilizing the comfort women in a broader sense, but I do not think that the Japanese government or the military was directly involved in mobilizing them [victims]” [40] and later stated to journalists that “there was no evidence to prove there was coercion as initially suggested” [41], contrary to evidence revealed by Yoshiaki in 1992. In 2012, Shinzo Abe and a group of right-wing Japanese politicians paid for a full page advertisement in the New York Times disparaging the victims of the Japanese military sexual slavery system as “willing prostitutes”. [42] Moreover, repeated official visits to the Yasukuni Shrine for the War Dead, where convicted war criminals are enshrined, by Japanese politicians, including Prime Ministers, has solidified Japan’s unrepentant attitude and contributed to the emergence of right-wing nationalism in Japan, as revisionists gained prominence and sought to justify Japan’s colonial past in order to protect Japan’s international image. [43] Japanese textbooks remain silent on any mention of its brutal colonial past and the Japanese Foreign Ministry has previously requested McGraw-Hill to remove references to the victims of Japanese military sexual slavery from American high school textbooks. [44,45]

Territorial disputes and ongoing disputes of forced labor by Japanese companies during Japan’s colonization of Korea stoke further bitter memories of the past. Relations between Japan and Korea were further strained when President Lee Myung-Bak visited the disputed Liancourt Rocks in 2012, emphasizing South Korea’s claim to the islands, later stating that “if Japan’s Emperor wishes to visit South Korea, I think it would be good if he apologizes sincerely to those who passed away while fighting for independence”. [46,47] Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda responded to the matter stating “I find [Lee’s statement] difficult to understand and extremely regrettable” [48], and another official was quoted as saying that “it has made it impossible for a Japanese Emperor to visit South Korea for the next 100 years”. [49]

South Korea’s decreasing dependence on Japan for production and capital goods has also contributed to increasing tensions between the two nations. [50] Globalization led to a shift in South Korea’s import sources, and the country has bolstered its parts and raw materials industries. Additionally, Japanese companies have increasingly shifted towards local production within South Korea, decreasing imports from Japan. And while, historically, governmental tensions between Japan and South Korea have not significantly impacted their economic relationship, lawsuits by South Koreans forced to work for Japanese companies during World War II have led to heightened tensions. In 2013, the Seoul High Court ordered compensation to be paid to victims of forced labor sparked fears that Japan’s colonial past could now affect business, leading Japanese business organizations to issue a rare joint statement in 2013, emphasizing the importance of resolving this issue for maintaining strong Japan-South Korea relations. Relations dropped to their lowest point in decades as a ruling from the South Korean Supreme Court in 2018 that ordered Japanese companies Mitsubishi and Nissan Steel to compensate the plaintiffs who were forced to work in their factories during Japan’s occupation of Korea was followed by the dissolution of the 2015 Japan–South Korea Comfort Women Agreement by South Korea in 2019, following escalating tensions after a Statue of Peace memorializing victims of Japan’s military sexual slavery was erected in Busan in 2017. [51,52]

V. Japan–South Korea Economic War (2019 – 2023)

Until this point, the worsening government relations had not had a significant impact on the economic relationships between the two countries. However, this changed in July 2019 when the Japanese Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) updated its licensing policies and procedures on exports of controlled items to Korea, notably photoresists and hydrogen fluoride, key semiconductor materials, stating that the “relationship of trust including in the field of export control and regulation has been significantly undermined”. [53–55] Japan claimed that it was taking action after coming to the conclusion that South Korea was leaking information and materials that could be used for military use to North Korea. [56] South Korea vehemently denied these accusations and stated that Japan was retaliating via economic means in response to the 2018 South Korean Supreme Court ruling regarding compensation of forced labor victims, a decision that could not be altered by the South Korean government. [57] Japan went further in August 2019 and revoked Korea’s preferential status as a trade partner for the purchase of goods that could be diverted for military use. [58]

Restrictions on key materials used for semiconductors, South Korea’s top export industry, introduced a level of economic uncertainty that had not previously existed since diplomatic relations were established in 1965. [59] Following the initial application of restrictions in July 2019, there was a flurry of action taken in the private sector with companies working to secure their supply chains for long-term production. [60] Additionally, barriers to South Korea’s ability to acquire key materials for semiconductor production would not only damage South Korea’s semiconductor industry, but would also affect buyers of Korean semiconductors, affecting everything from smartphones to automobiles. [61] Understanding the potential economic impact of Japan’s trade restrictions, South Korea filed a complaint with the World Trade Organization (WTO) regarding Japan’s trade restrictions of semiconductor material export to South Korea, and in September 2023, South Korea responded to the trade restrictions by removing Japan from its own white list of countries with fast track trade status. [62–64]

The trade dispute continued until South Korean President Yoon Suk-Yeol visited Japan on March 16, 2023 in order to resolve the trade dispute. On March 21, 2023 South Korea announced that Japan would be restored to the country’s trade white list. On March 23, 2023, Japan and Korea took joint action with Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry restoring South Korea’s white list status, and South Korea withdrawing their WTO complaint, ending the four year trade dispute. [65–67]

VI. Economic Impact and Long-Term Implications

The trade dispute caused waves globally due to the potential political and economic ramifications of the dispute. Escalating tensions between Japan and South Korea threatened to undermine regional economic and security agreements, and create a power vacuum in the semiconductor industry that China certainly had motivations to fill. [68,69] Even more concerning was this dispute was helping to normalize weaponizing national security concerns to justify trade policy. [70,71]

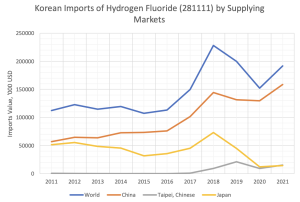

At the time, experts warned that this move could backfire on Japan down the road as South Korean companies would be forced to rethink supply chains. [72] We see exactly that happen based on headlines between May 2021 and August 2023, as the Korean government and Korean companies have started to invest billions of dollars into domestic semiconductor production and localizing 50% of chip materials to support the growth and self-reliance. [73–75] Samsung Electronics opened a new Semiconductor R&D Complex in 2022, and the Korean government established relationships with China to source advanced chip making equipment for weapons systems. [76,77] Data from Japan (Figure 1) also indicated that these trade restrictions damaged its own hydrogen fluoride industry and lost Korea, their biggest buyer. Should South Korea be successful in semiconductor localization, we could expect “Japan’s per capita income to fall permanently”. [78]

Figure 1: Korean Imports of Hydrogen Fluoride by Supplying Markets (Source: Yong June Hong)

VII. War Memory Impacting Semiconductor Supply Chains

Although Japan’s reasoning for the levying the trade restrictions was due to unsubstantiated claims that South Korea was leaking information and materials that could be used for military use to North Korea, the core issue of the dispute was not one of economic and security concern, but one of economics and security concerns being weaponized to reflect years of historical disputes between the two nations. [79] This is evident based on South Korean president Moon Jae-In’s opening remarks during an emergency cabinet meeting following the levying of trade restrictions, noting that the trade restrictions were “undeniable trade retaliation against our Supreme Court’s rulings on Korean victims of forced labor during colonial rule” [80] and that South Korea would “never again lose to Japan.” [81] With this address, it is clear that this dispute was triggered by South Korea’s government and activists’ continued efforts for Japan to acknowledge and apologize for its colonial past, and provide compensation to victims.

Additionally, signs from Korean protests (Figure 2) following the trade dispute are emblazoned with the handprint of An Jung-geun, a Korean independence activist, who “cut off the tip of his ring finger as he swore to work to restore [his] country’s sovereignty”. [82] With this, it is clear that the Korean boycott of Japanese goods in response to the trade restrictions was tied to the memory of Japanese colonialism and a desire to fight against Japanese aggression, be that military or economic.

Figure 2: Signs from Boycott Japan protests in 2019 (Kukin News)

And while, the South Korean government identified the trade restrictions as the 2018 South Korean Supreme Court ruling regarding compensation of forced labor victims, I argue that the trade restrictions was the first instance of economic retaliation after years of tension surrounding Japan’s colonial past, that the victims of Japanese military sexual slavery had become symbols of. This is exemplified by Lee Yong-soo, a survivor of Japan’s military sexual slavery system, and Yang Geum-deok, a survivor of forced labor, joining a rally in March 2023 calling for a formal apology and reparations from Japan for its colonial past. [83,84] Additionally, a change in political tides following the 2015 Comfort Women Agreement created the conditions and pressure for the South Korean Supreme Court to rule in favor of forced labor victims.

VIII. Implications for Future Diplomacy

Understanding that the 2019 trade dispute was retaliation against South Korea’s continued activism to address Japan’s colonial past and crimes, we can then understand why agreement after agreement has failed to resolve these issues. Agreements facilitated by the United States have always been more about “political expediency than a sincere attempt for a real reconciliation”. [85] The 2015 Comfort Women Agreement failed to resolve historical injustices, hold Japan accountable for its actions during World War II, and excluded South Korean victims and civic groups from the process, just as the post-war 1965 Treaty on Basic Relations did. While the approach of political expediency served the United States and Japan well post-World War II, “human rights norms [today] have changed the rules of the game in resolving historical disputes” [86] and the importance of Japan to South Korea has decreased in economic terms. [87] Democratization and advances in information technology have also increased public awareness of issues the previous government may have ignored, and a growing tendency by the public to demand the disclosure of information has triggered examinations of issues that may have been previously considered resolved. [88]

One critical issue has been the question of whether Japan should accept legal responsibility for the crimes committed during World War II. Legal responsibility is what victims and victim advocates have been pushing for since the 1990s, and it goes without saying that any settlement between Japan and South Korea should be based on a dialogue with the victims of sexual slavery and forced labor. The traumatic experience of sexual slavery and forced labor has left many physical and emotional scars behind, and providing the victims with a sincere apology and adequate compensation will be a cornerstone of any meaningful agreement.

However, Japan’s reluctance to address their colonial past presents a significant challenge in pursuing justice through international human rights law. Additionally, there are many nations that might oppose such measures. Acknowledging Japan’s war crimes and holding it accountable would set legal precedent, potentially leading to similar claims against countries with a history of colonialism and wartime atrocities. The reluctance to establish a legal precedent for a colonized nation successfully suing its colonizer in a court of law highlights the broader challenges in achieving global justice for war crimes. These complexities illustrate the tension between the pursuit of justice, and the political and legal ramifications that such actions entail.

That being said, holding Japan accountable for its war crimes during World War II, particularly the systematic use of sexual slavery and forced labor, sets a critical precedent in the international community. It underscores the importance of acknowledging and addressing the use of rape as a weapon of war, which has implications across history, including in present day conflicts in Palestine and Sudan. Recognizing these atrocities and holding perpetrators accountable sends a powerful message that such inhumane acts will not be tolerated and that justice must prevail, regardless of when the crimes were committed.

Sources:

[1] The Japanese Colonial Empire, 1895-1945 by Ramon H. Myers and Mark R. Peattie

[2] Brokers of Empire: Japanese Settler Colonialism in Korea, 1876–1945 by Jun Uchida

[3] The Japanese Colonial Empire, 1895-1945 by Ramon H. Myers and Mark R. Peattie

[4] Brokers of Empire: Japanese Settler Colonialism in Korea, 1876–1945 by Jun Uchida

[5] Brokers of Empire: Japanese Settler Colonialism in Korea, 1876–1945 by Jun Uchida

[6] Brokers of Empire: Japanese Settler Colonialism in Korea, 1876–1945 by Jun Uchida

[7] Brokers of Empire: Japanese Settler Colonialism in Korea, 1876–1945 by Jun Uchida

[8] https://www.monash.edu/arts/languages-literatures-cultures-linguistics/korean-studies-research-hub/research/on-this-day-in-korean-history/on-this-day-in-korean-history-13-8.15-liberation-day

[9] Colonial Rule and Social Change in Korea, 1910-1945 by Hong Yung Lee, Yong Chool Ha, and Clark W. Sorensen

[10] https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/nation/2023/11/137_82414.html

[11] The Japanese Colonial Empire, 1895-1945 by Ramon H. Myers and Mark R. Peattie; Chapter 7 – Colonial Education in Korea and Taiwan by E. Patricia Tsurumi

[12] Colonial Rule and Social Change in Korea, 1910-1945 by Hong Yung Lee, Yong Chool Ha, and Clark W. Sorensen

[13] https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/nation/2023/11/137_82414.html

[14] https://www.history.com/news/japan-colonization-korea

[15] https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/nation/2023/11/137_82414.html

[16] https://www.history.com/news/japan-colonization-korea

[17] https://www.history.com/news/japan-colonization-korea

[18] https://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/14997813

[19] https://www.csmonitor.com/World/Asia-Pacific/2023/0901/For-Koreans-in-Japan-this-little-known-massacre-still-carries-weight

[20] https://apjjf.org/-Sonia-Ryang/2513/article.html

[21] https://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Article/E0004775

[22] https://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Article/E0002635

[23] Comfort Women: Sexual Slavery in the Japanese Military During World War II by Yoshimi – Yoshimi, Y. and O’Brien, S.

[24] https://ace-usa.org/blog/research/research-foreignpolicy/overview-of-japanese-colonial-rule-in-korea

[25] https://web.archive.org/web/20220318100845/https://aeon.co/essays/against-han-or-why-koreans-are-not-defined-by-sadness

[26] https://www.history.com/news/japan-colonization-korea

[27] https://www.archives.gov/files/iwg/japanese-war-crimes/introductory-essays.pdf#

[28] https://wrlc-gu.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01WRLC_GUNIV/1hdki3o/cdi_nrf_kci_oai_kci_go_kr_ARTI_1378296

[29] https://womenandwar.net/kr/what-is/

[30] Obama’s Pivot to Asia and Its Failed Japan-South Korea Historical Reconciliation by Chien Liu

[31] https://kls.law.columbia.edu/content/lawsuits-brought-against-japan-former-korean-comfort-women

[32] Interview with Alexis Dudden, Ph.D., Professor, Department of History at University of Connecticut, Conducted by Zainab Ahmed

[33] Obama’s Pivot to Asia and Its Failed Japan-South Korea Historical Reconciliation by Chien Liu

[34] The so-called 2015 Agreement between Japan and South Korea and the Korean Comfort Women Issue by Boris Kondoch

[35] Obama’s Pivot to Asia and Its Failed Japan-South Korea Historical Reconciliation by Chien Liu

[36] Obama’s Pivot to Asia and Its Failed Japan-South Korea Historical Reconciliation by Chien Liu

[37] Japan and Korea: Why Can’t they Reconcile? by Taehyo Kim (김태효)

[38] Obama’s Pivot to Asia and Its Failed Japan-South Korea Historical Reconciliation by Chien Liu

[39] https://kls.law.columbia.edu/content/lawsuits-brought-against-japan-former-korean-comfort-women

[40] Obama’s Pivot to Asia and Its Failed Japan-South Korea Historical Reconciliation by Chien Liu

[41] https://www.mjilonline.org/south-korean-and-japanese-diplomatic-crisis-over-comfort-women-statue/

[42] https://www.mjilonline.org/south-korean-and-japanese-diplomatic-crisis-over-comfort-women-statue/

[43] Obama’s Pivot to Asia and Its Failed Japan-South Korea Historical Reconciliation by Chien Liu

[44] Obama’s Pivot to Asia and Its Failed Japan-South Korea Historical Reconciliation by Chien Liu

[45] https://www.mjilonline.org/south-korean-and-japanese-diplomatic-crisis-over-comfort-women-statue/

[46] https://www.jri.co.jp/MediaLibrary/file/english/periodical/rim/2014/51.pdf

[47] https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20120814008100315

[48] https://www.ibtimes.co.uk/sex-slave-comfort-woman-japan-south-korea-374461

[49] https://www.ibtimes.co.uk/sex-slave-comfort-woman-japan-south-korea-374461

[50] https://web.archive.org/web/20120815072424/http://ajw.asahi.com/article/asia/korean_peninsula/AJ201208140048

[51] The so-called 2015 Agreement between Japan and South Korea and the Korean Comfort Women Issue by Boris Kondoch

[52] https://www.ibtimes.co.uk/sex-slave-comfort-woman-japan-south-korea-374461

[53] https://www.meti.go.jp/english/press/2019/0701_001.html

[54] https://www.meti.go.jp/english/press/2019/0701_001.html

[55] https://theowp.org/trade-war-between-japan-and-south-korea/

[56] https://www.vox.com/world/2019/8/9/20758025/trade-war-south-korea-japan

[57] https://web.archive.org/web/20190729213526/https://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20190701/p2g/00m/0na/051000c

[58] https://www.vox.com/world/2019/8/9/20758025/trade-war-south-korea-japan

[59] https://thediplomat.com/2020/01/parsing-the-economic-damage-from-the-japan-south-korea-dispute/

[60] https://web.archive.org/web/20190729213526/https://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20190701/p2g/00m/0na/051000c

[61] https://web.archive.org/web/20190729213526/https://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20190701/p2g/00m/0na/051000c

[62] https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/news19_e/ds590rfc_16sep19_e.htm

[63] https://www.cnn.com/2019/08/02/business/japan-south-korea-trade-war/index.html

[64] ttps://thediplomat.com/2019/08/south-korea-strikes-back-removes-japan-from-trade-white-list/

[65] https://apnews.com/article/japan-south-north-korea-unification-minister-a399cb15715d827105563f279a9996e1

[66] https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20230323007900320

[67] https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/news23_e/disp_24mar23_e.htm

[68] https://theowp.org/trade-war-between-japan-and-south-korea/

[69] https://english.kyodonews.net/news/2019/08/9e957002f242-focus-japan-s-korea-rift-may-change-regional-economic-security-structures.html

[70] https://theowp.org/trade-war-between-japan-and-south-korea/

[71] https://www.vox.com/world/2019/8/9/20758025/trade-war-south-korea-japan

[72] https://theowp.org/trade-war-between-japan-and-south-korea/

[73] https://www.datacenterdynamics.com/en/news/south-korea-to-spend-451-billion-to-become-semiconductor-manufacturing-giant/

[74] https://www.argusmedia.com/en/news/2463333-s-korea-launches-230mn-semiconductor-ecosystem-fund

[75] https://www.kedglobal.com/tech%2C-media-telecom/newsView/ked202304100021

[76] https://news.samsung.com/global/samsung-electronics-breaks-ground-on-new-semiconductor-rd-complex-in-giheung-korea

[77] https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Tech/Semiconductors/South-Korea-welcomes-new-rules-easing-chip-tool-shipments-to-China

[78] https://www.ucl.ac.uk/economics/sites/economics/files/20_yong_june_hong.pdf

[79] https://web.archive.org/web/20190729213526/https://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20190701/p2g/00m/0na/051000c

[80] https://www.korea.net/Government/Briefing-Room/Presidential-Speeches/view?articleId=173815&pageIndex=1

[81] https://www.korea.net/Government/Briefing-Room/Presidential-Speeches/view?articleId=173815&pageIndex=1

[82] https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/nation/2023/12/113_49322.html

[83] https://web.archive.org/web/20120815072424/http://ajw.asahi.com/article/asia/korean_peninsula/AJ201208140048

[84] https://english.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/e_national/1081910.html

[85] Obama’s Pivot to Asia and Its Failed Japan-South Korea Historical Reconciliation by Chien Liu

[86] Obama’s Pivot to Asia and Its Failed Japan-South Korea Historical Reconciliation by Chien Liu

[87] Obama’s Pivot to Asia and Its Failed Japan-South Korea Historical Reconciliation by Chien Liu

[88] https://www.jri.co.jp/MediaLibrary/file/english/periodical/rim/2014/51.pdf